| Monthly Tech-Tip | No tracking! No ads! |

Make your own vibrating sieve

And process your own super-fine clays

Being more independent is now cool again. Actually, it is being forced upon us by necessity because of supply chain issues and skyrocketing prices of convenience glazes, bodies, engobes, etc. Independence involves using sieves. True, it is no problem for a potter or lab tech to manually coax a glaze slurry through a small 80# sieve. But real independence is about sieving in volume - clay bodies made from your own native clays. And doing it at up to 325 mesh. That requires a vibrating sieve. This one cost us less than $100 to make. Of course, a Tyler sieve (or similar) is needed, these can be purchased on Ebay or Amazon. And a vibration motor, some metal and hardware and a friend with metal fabrication tools. This demonstrates the utility of a vibrating sieve, the idea can be scaled to any size you need. As an example, oil well drilling sites here have to remove particulates from huge volumes of drilling mud and they do it on giant multi-level units.

Related Pictures

These are behind the art center. A dirty secret. Or an opportunity!

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

When many clays are in use there is good reason to collect like this - you will see why in a moment. Each barrel is a unique product, a mix of random clays used by students. Each could be thus considered a wild clay, inconsistent throughout and with impurities. As such, each needs to be characterized, as a whole. For example, consider the front barrel: What does it look like when fired at various temperatures? At what temperature does it mature? What is the drying shrinkage and how plastic is it? Does it fit the glazes we use? This information not only describes the clay but also points to what needs to be added to make it useful (e.g. bentonite or feldspar). An account at Insight-Live.com is a way to organize the testing and post the results to a group (the SHAB test, for example, is perfect to describe the plastic, drying and firing properties). Once the clay in a barrel becomes predictable then it becomes useful.

To do the testing it is necessary to get a representative sample from each barrel. The method depends on how processing will be done. In a wet climate, the wet contents are likely to be thrown into a pugmill (with impurities), recycled until mixed and then bagged - a sample can be taken when complete. But the dry climate option is much better: Dewater each barrel, do quartering to get a representative sample and then characterize it. Finally, slake, slurry up batches using a propeller mixer, screen in a vibrating sieve and then dewater (e.g. on a plaster table).

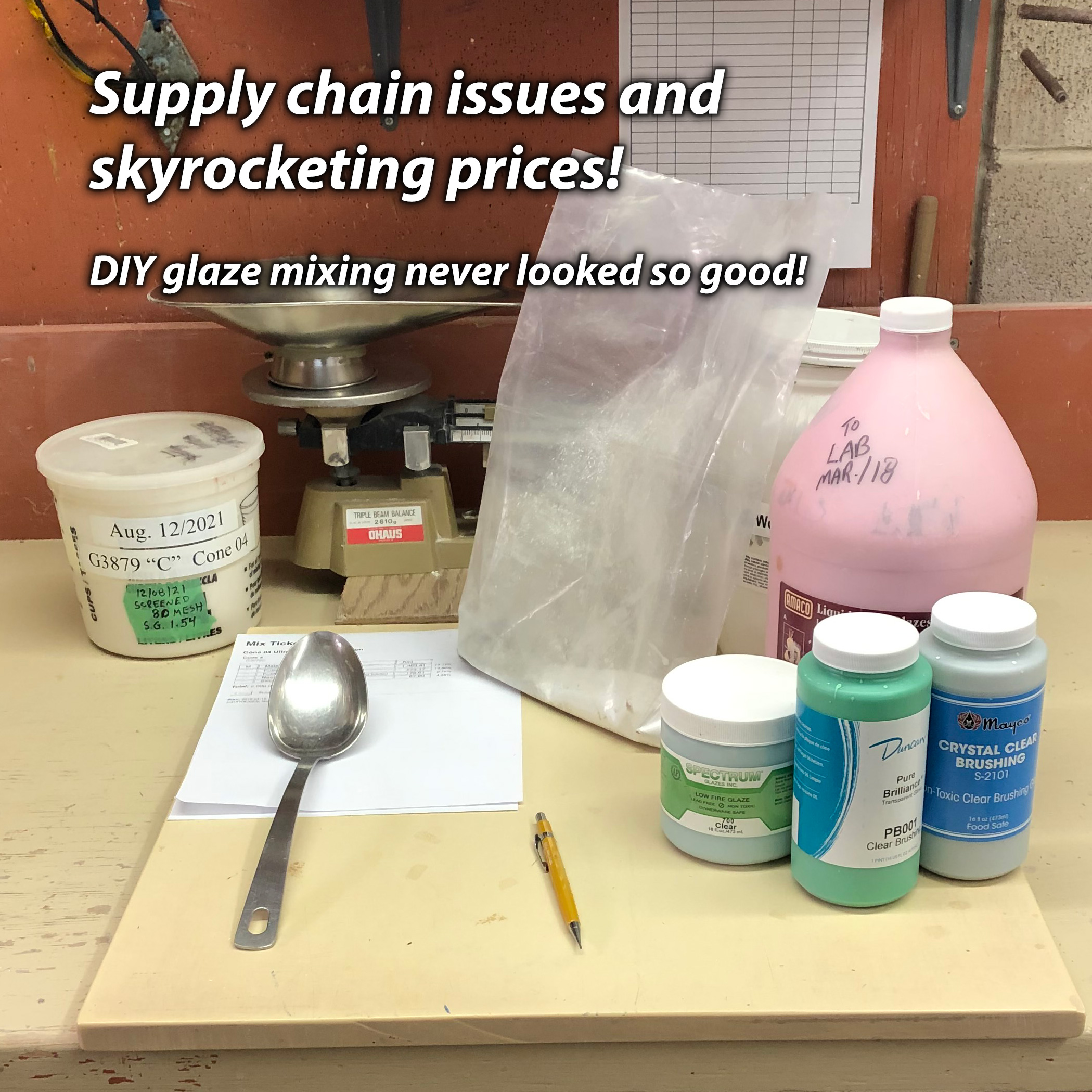

Global supply chain issues? Learn to mix and adjust your own bodies, glazes

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Material prices are sky rocketing. And, the more complex your supplier's supply chain the more likely they won't be able to deliver. How can you adapt to coming disruption, even turn it into a benefit? Learn to create base recipes for your glazes and even clay bodies. Learn now how to substitute frits and other materials in glazes (get the chemistry of frits you use now so you are ready). Even better: Learn to see your glaze as an oxide formula. Then calculate formula-to-batch to use whatever materials you can get. Learn how to adjust glazes for thermal expansion, temperature, surface, color, etc. And your clay bodies? Develop an organized physical testing regimen now to accumulate data on their properties, learn to understand how each material in the recipe contributes to those properties. Armed with that data you will be able to adjust recipes to adapt to changing supplies.

When Supply Chains Broke, Prices Soared.

We haven’t forgotten. Time for DIY!

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Material prices were sky rocketing (and still are). Prepared glaze manufacturers have complex international supply chains. Now might be the time to start learning how to weigh out the ingredients to make your own. Armed with good base glazes that fit your clay body (without crazing or shivering) you will be more resilient to supply issues. Add stains, opacifiers and variegators to the bases to make anything you want. That being said, ingredients in those recipes may become unavailable! That underscores a need to go to the next step and "understand" glaze ingredients. And even improve and adjust recipes. It is not rocket science, it is just work accompanied by organized record-keeping and good labeling.

Videos

Links

| Projects |

Make your own sieve shaker to process ceramic slurries

All you need is an inexpensive vibration motor from Amazon, a five-gallon pail, some metal and welding and 3D-printed collars to hold the sieve in place. |

| Glossary |

Sieve Shaker

A device that can vibrate a sieve thus greatly increasing the speed at which it can process a slurry or powder. |

| Glossary |

Sieve

Sieves are important in ceramics for removing particulates and agglomerates from glaze, engobe and body slurries. |

Got a Question?

Buy me a coffee and we can talk

https://digitalfire.com, All Rights Reserved

Privacy Policy