| Monthly Tech-Tip | Feb 14-15, 2026 - Major Server Upgrade Done | No tracking! No ads! |

Feldspar

| Oxide | Analysis | Formula | Tolerance |

|---|---|---|---|

| K2O | 16.92% | 1.00 | |

| Al2O3 | 18.32% | 1.00 | |

| SiO2 | 64.76% | 6.00 | |

| Oxide Weight | 556.74 | ||

| Formula Weight | 556.74 | ||

Notes

Theoretically speaking, the term 'feldspar' refers to a family of minerals with a specific crystalline presence. However actual feldspar powders are made from crushed crystalline rock containing a mixture of aluminum silicates of sodium and potassium (with minor amounts of lithium or calcium). They normally contain 10-15% alkali (K2O, Na2O) and melt well at medium to high temperatures and are an economic source of flux. Commercially available feldspars tend to predominate in one specific mineral kind with lesser amounts of another and traces of others. Manufacturers can be found around the world and they usually do a good job of delivering uniform and clean products when one considers that feldspar deposits vary widely in composition and contain many impurities. Large quantities of feldspar are used in non-ceramic industry (e.g. cement, agri).

In many countries feldspar companies draw upon the same mine year and year, marketing a brand name product that gains wide acceptance. In other countries (e.g. India) large feldspar suppliers do not even have mines, they buy raw product according to the chemistry and blend from different sources to achieve a specific product. Over time they change suppliers but through careful quality control, their ceramic manufacturing customers often do not realize their feldspar is coming from different sources with different shipments. Increasingly customers are connecting with suppliers on other continents, not infrequently this has led to misunderstandings and delivery of bad or variable product.

Generally, high potash feldspars are employed in bodies and promote vitrification by forming a glassy phase that 'cements' more refractory particles together and triggers the formation of mullite from clay mineral. It is typical to see about 25% feldspar in cone 10 vitreous bodies (1300C) and 35% at cone 6 (1200C), although porcelains may have a little more. Much below 1200C feldspar will not produce a vitreous body. Manufacturers often employ feldspar percentages inappropriate to their situations and other materials (like silica sand, alumina, extra quartz) are added to compensate. It is important to test the porosity and fired shrinkage of your body at temperatures above and below your production firing (e.g. -30, -60, -90, +30, +60, +90). This will tell you where you are on the porosity and shrinkage curves (it is not good to be near or on the down-slope of the firing shrinkage or up-slope of the porosity). You can organize this testing in your account at insight-live.com.

In glazes, feldspar promotes melting at medium and high temperatures (feldspars are the primary ingredient in most high-temperature raw glazes). Sodium feldspars are most common and used mainly as a source of alkalis. Feldspars are mineral compounds of silica, alumina and fluxes and are among the relatively few insoluble sources of K2O, Na2O and Li2O. No other raw material is closer to being a complete stoneware glaze on its own than feldspar. Since feldspars contain a complex mix of oxides, ceramic chemistry calculations are needed to 'juggle' a recipe to achieve the desired balance of fluxing oxides with alumina and silica and to control the high thermal expansion that they impart.

Many feldspars begin to melt around 2100F (1150C) and make good glaze bases because they contribute alumina and silica in forms that participate well in the melt. Feldspars tend to work well in fast-fire high-temperature glazes because they remain relatively inert until the later stages of firing.

Geologists see feldspar as a mineral and classify feldspars mainly as albite, microcline, orthoclase and anorthite. However, for use in glazes, we can view feldspars as 'warehouses of oxides' (e.g. because they supply K2O, Na2O, Al2O3 and SiO2 to the glaze melt).

Alert

'Flux-saturated' glazes with high feldspar contents tend to be chemically unbalanced and thus make poor bases for functional ware, especially for glaze containing metallic color oxides (the glazes can be soft, leachable, crazed, oxidizable). High feldspar can contribute to a high surface tension in the glaze melt and may lead to high bubble population (producing milkiness in the fired matrix). Stoneware glazes using large amounts of feldspar as a flux almost always craze because high-expansion sodium and potassium predominate. High feldspar glazes often lack clay content and thus do not suspend well, they settle in a hard layer on the bottom of the container and dry to a powdery surface on ware. In fact, thousands of potters are using feldspar saturated glazes and living with many problems without being aware of the cause.

Related Information

Stockpile of crude feldspar from MGK Minerals (India) deposit

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Closeup of feldspar deposit in the MGK Minerals quarry in India

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Feldspars, the primary high temperature flux, melt less than you think.

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Our melt fluidity tester is being used to compare cone 8 melt fluidities of Custer, G-200 and i-Minerals high soda and high potassium feldspars. Notice how little the pure materials are moving (bottom), even though they are fired to cone 11. In addition, the sodium feldspars move better than the potassium ones. But feldspars do their real fluxing work when they can interact with other materials. As a demonstration of that, note how well they flow with only 10% frit added (top), even though fired three cones lower.

A soda feldspar applied like at glaze at cone 4-7

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

This is pure soda feldspar (Minspar 200) fired like a glaze at cone 4, 5, 6 and 7 on porcelainous stoneware tiles. The bottom samples are balls that have melted down at cone 7 and 8 (although they appear to be well melted they exhibit no movement in a melt fluidity test. Notice there is no melting at all at cone 4. Also, serious crazing is highlighted with ink on the cone 6 sample (it is also happening at cone 5 and 7). Feldspars have high KNaO, that means they have high thermal expansions. That is why high-feldspar glazes almost always craze. Since feldspar is barely melting at cone 6 it is not possible to make a functional cone 6 glaze that only uses feldspar as the flux (boron, lithia or zinc are also needed).

Craze city: Feldspar and Nepheline Syenite on cone 10R porcelain bodies

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

These were applied to the bisque as a slurry (suspended by gelling with powdered or dissolved Epsom salts). On the left is Custer feldspar, the right is Covia Nepheline Syenite. Notice the crazing (feldspars, and nepheline syenite, always craze because they are high in K2O and Na2O, these oxides have by far the highest thermal expansions).

This feldspar melts by itself to be a glaze, but crazes badly

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Pure MinSpar feldspar fired at cone 6 on Plainsman M370 porcelain. Although it is melting, the crazing is extreme! And expected. Feldspars contain a high percentage of K2O and Na2O (KNaO), these two oxides have the highest thermal expansion of any oxide. By far! Thus, glazes high in feldspar (e.g. 50%) are likely to craze. Using a little glaze chemistry, it is often possible to substitute some of the KNaO for another fluxing oxide having a lower thermal expansion.

A down side of high feldspar glazes: Crazing!

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

This reduction celadon is crazing. Why? High feldspar. Feldspar supplies the oxides K2O and Na2O, they contribute the brilliant gloss and great color but the price is very high thermal expansion. Scores of recipes being traded online are high-feldspar, some more than 50%! There are ways to tolerate the high expansion of KNaO, but the vast majority are crazing on all but high quartz bodies. Crazing is a plague for potters. Ware strength suffers dramatically, pieces leak, the glaze can harbor bacteria and customers return pieces. The simplest fix is to transplant the color and opacity mechanism into a better transparent, one that fits your ware (in this glaze, for example, the mechanism is simply an iron addition). Fixing the recipe may also be practical. A 2:1 mix of silica:kaolin has the same Si:Al ratio as most glossy glazes, this glaze could possibly tolerate 10% of that. That would reduce running, improve fit and increase durability. Failing that, the next step is to substitute some of the high-expansion KNaO, the flux, for the low-expansion MgO, that requires doing some glaze chemistry.

Getting the feldspar percentage right in an iron reduction clay body

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

We are trying to achieve a body sufficiently vitreous for functional ware but open enough to still have the characteristic variegated patching of light and dark brown (with reduction iron speck of course). Our base recipe is a two-part mix of red and buff fireclay. Mugs #1 and #2 have 12% Custer feldspar but #2 has more of the white clay (it’s more refractory and more plastic - so #2 has a porosity of 3.5% while #1 has 2.8%). #3 has the same clay mix as #2 but it uses 12% Nepheline Syenite - it’s greater fluxing power has turned the color a solid brown (and dropped porosity to 1.5%). The next step: We will target 3% porosity in #3 using a reduced percentage of Nepheline, likely about 9%. We have depended on 100% clay mixes in the past and the body has suffered variations in density (as measured by our SHAB test) and has seldom hit the 3% porosity target, having feldspar in the recipe will enable accurately controlling it in future (so we are more comfortable recommending it for light duty functional ware).

Feldspar from Okene, Koji, Nigera

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

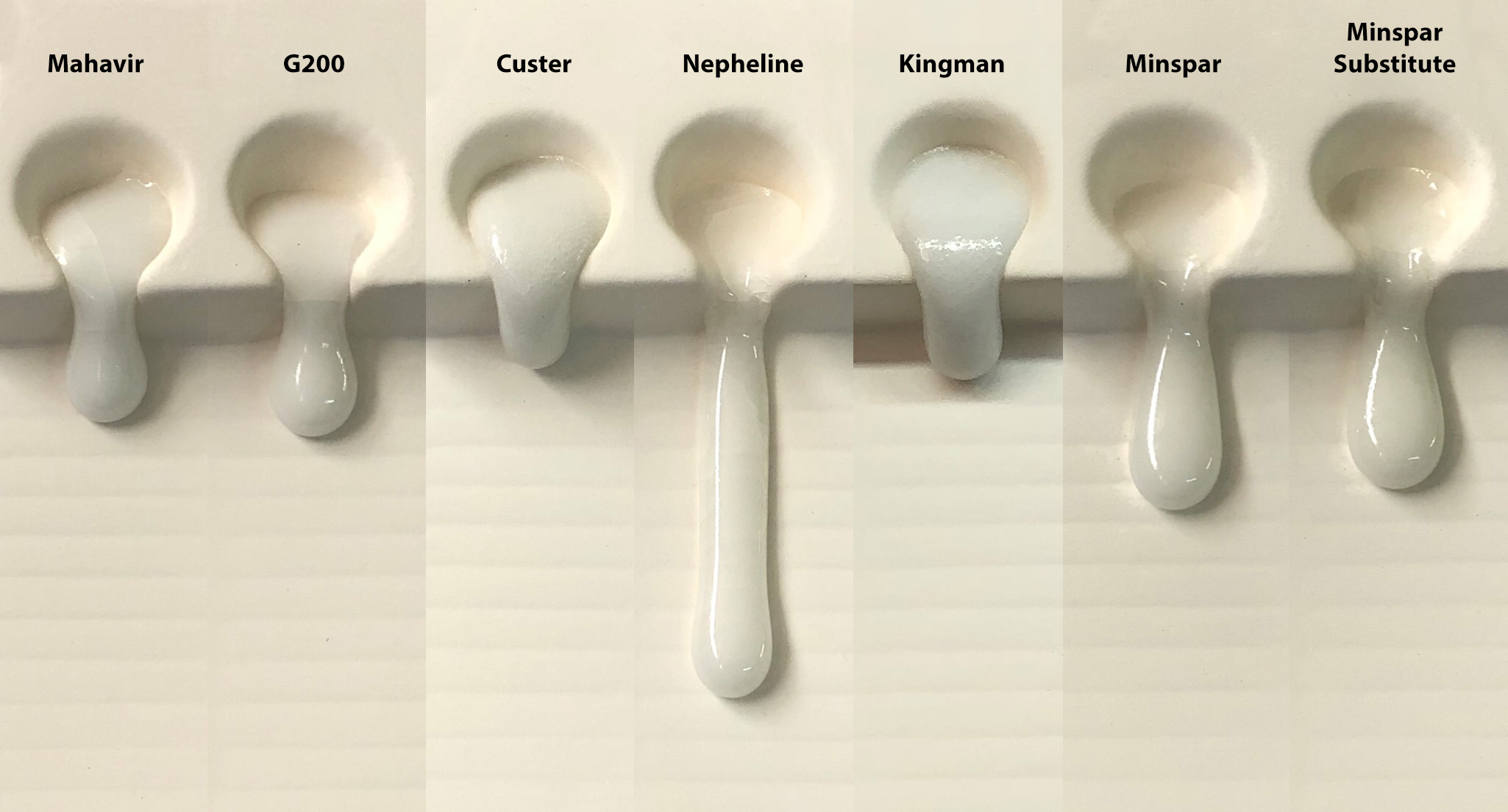

Which is the champion melter of American/Canadian feldspars?

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Feldspars are employed in glaze recipes as melters. So comparing their melt fluidities should be helpful in deciding if one can substitute for another (of course, if possible, a soda-predominant feldspar should be substituted for another soda spar). Feldspars don't melt alone at cone 6 (2200F) so we mixed each with 15% Ferro Frit 3195 (we consider a feldspar a material that sources KNaO). Nepheline Syenite, this is A270, is the champion melter here. Other similar ones can be spotted easily. In the end, degree of melt is a valid consideration in determining if one feldspar is a viable substitute for another in a recipe. Even if the feldspar you want to substitute does not melt as much a little frit can be added to the recipe to make up for the difference (e.g. 3-5%).

High feldspar glazes craze. Don't put up with it.

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

This glaze, "Bamboo Cone 10%", contains 50% potash feldspar so or certainly qualified as a high feldspar glaze. K2O and Na2O are this over supplied. They have the highest thermal expansions of all oxides, by far. These are needed and valuable - but when grossly over supplied the result is crazing. This glaze used to work on this body, H550. The previous version of H550 was firing near the bloating point of the body, about 1% porosity, so the recipe had to be changed to provide more margin for error. The new recipe has a more practical 2.0-2.5% porosity, it has no danger of bloating or warping and still has excellent maturity and strength. This glaze was crazing before and pieces did not leak because the body was dense enough - so they were still water tight. But now it does not work. The solution is to do something that should have been done before: Use a silky matte base recipe that does not craze. We recommend our G2571A base (below right) - the Zircopax, rutile and iron oxide in the original can be added to it instead.

Links

| Articles |

A Low Cost Tester of Glaze Melt Fluidity

Use this novel device to compare the melt fluidity of glazes and materials. Simple physical observations of the results provide a better understanding of the fired properties of your glaze (and problems you did not see before). |

| Articles |

Formulating a Porcelain

The principles behind formulating a porcelain are quite simple. You just need to know the purpose of each material, a starting recipe and a testing regimen. |

| Articles |

Are Your Glazes Food Safe or are They Leachable?

Many potters do not think about leaching, but times are changing. What is the chemistry of stability? There are simple ways to check for leaching, and fix crazing. |

| Articles |

Crazing in Stoneware Glazes: Treating the Causes, Not the Symptoms

Band-aid solutions to crazing are often recommended by authors, but these do not get at the root cause of the problem, a thermal expansion mismatch between glaze and body. |

| Articles |

Is Your Fired Ware Safe?

Glazed ware can be a safety hazard to end users because it may leach metals into food and drink, it could harbor bacteria and it could flake of in knife-edged pieces. |

| Articles |

Bringing Out the Big Guns in Craze Control: MgO (G1215U)

MgO is the secret weapon of craze control. If your application can tolerate it you can create a cone 6 glaze of very low thermal expansion that is very resistant to crazing. |

| URLs |

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Feldspar

Feldspar at Wikipedia |

| URLs |

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Feldspar

Wikipedia Feldspar Page |

| URLs |

http://studiopotter.org/pdfs/Sohng%20pps84-89.pdf

Article about cristobalite in clay bodies |

| URLs |

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FVUuhjnjAoA

German potter Cornelius Breymann investigates limit formulas, eutectics On this Youtube video Cornelius will take you on a slow and deliberate journey. If you stick with him you will discover how, by industrious blending of feldspar, calcium carbonate and silica we can see what ratios of CaO, SiO2 and Al2O3 (and the materials sourcing them) produce a well-melted high temperature glaze. You will see how the process demonstrates where feldspar comes up short as a glaze by itself and what it needs to be one. And you will see the CaO:SiO2:Al2O3 eutectic demonstrated. |

| Materials |

Custer Feldspar

The most common potash feldspar used in ceramics in North America. While having been a standard for many decades its supply appears in doubt in 2024. |

| Materials |

Soda Feldspar

A feldspar having a KNaO content that predominates in sodium. |

| Materials |

Potash Feldspar

A feldspar having a KNaO content that predominates in potassium. |

| Materials |

Calcium Feldspar

|

| Materials |

Spodumene

Spodumene is a lithium sourcing feldspar, an alternative to lithium carbonate to supply Li2O to ceramic glazes. Contains up to about 8% Li2O. |

| Materials |

Nepheline Syenite

|

| Materials |

Nepheline Syenite Norwegian

|

| Materials |

Ferro Frit 3110

High sodium, high thermal expansion low boron frit. A super-feldspar in clay bodies. Melts a very low temperatures. |

| Materials |

Feldspath ICE 10

|

| Materials |

Kaolin A

|

| Materials |

Pegmatite

|

| Materials |

Minspar 200

|

| Materials |

Kona F-4 Feldspar

|

| Materials |

M-200 Feldespato

|

| Materials |

G-200 2R Feldspar

|

| Hazards |

Feldspar

Feldspars are abundant and varied in nature. They contain small amounts of quartz (while nepheline syenite does not). |

| Typecodes |

Feldspar

The most common source of fluxes for high and medium temperature glazes and bodies. |

| Typecodes |

Generic Material

Generic materials are those with no brand name. Normally they are theoretical, the chemistry portrays what a specimen would be if it had no contamination. Generic materials are helpful in educational situations where students need to study material theory (later they graduate to dealing with real world materials). They are also helpful where the chemistry of an actual material is not known. Often the accuracy of calculations is sufficient using generic materials. |

| Typecodes |

Feldspar

The most common source of fluxes for high and medium temperature glazes and bodies. |

| Troubles |

Powdering, Cracking and Settling Glazes

Powdering and dusting glazes are difficult and a dust hazard. Shrinking and cracking glazes fall off and crawl. The cause is the wrong amount or type of clay. |

| Troubles |

Glaze Crazing

Ask the right questions to analyse the real cause of glaze crazing. Do not just treat the symptoms, the real cause is thermal expansion mismatch with the body. |

| Oxides | Al2O3 - Aluminum Oxide, Alumina |

| Oxides | Na2O - Sodium Oxide, Soda |

| Oxides | Li2O - Lithium Oxide, Lithia |

| Oxides | SiO2 - Silicon Dioxide, Silica |

| Oxides | KNaO - Potassium/Sodium Oxides |

| Media |

Mica and Feldspar Mine of MGK Minerals

|

| Media |

A Broken Glaze Meets Insight-Live and a Magic Material

Use Insight-Live.com to do major surgery on a feldspar saturated cone 10R glaze recipe with multiple issues: blistering, pinholing, crazing, settling, dusting and possibly leaching! |

| Glossary |

Crackle glaze

Crackle glazes have a crack pattern that is a product of thermal expansion mismatch between body and glaze. They are not suitable on functional ware. |

| Glossary |

Feldspar Glazes

Feldspar is a natural mineral that, by itself, is the most similar to a high temperature stoneware glaze. Thus it is common to see alot of it in glaze recipes. Actually, too much. |

Mechanisms

| Body Maturity | Feldspar is the most important body flux for cone 2+. Many clays and other body materials contain feldspar. The classic cone 10 porcelain recipe is 25% each of feldspar, ball clay, silica and kaolin. |

|---|

| By Tony Hansen Follow me on        |  |

Got a Question?

Buy me a coffee and we can talk

https://digitalfire.com, All Rights Reserved

Privacy Policy