| Monthly Tech-Tip | Feb 14-15, 2026 - Major Server Upgrade Done | No tracking! No ads! |

Base Glaze

Understand your a glaze and learn how to adjust and improve it. Build others from that. We have bases for low, medium and high fire.

Key phrases linking here: base transparent, base recipes, cover glazes, base recipe, cover glaze, base glazes, base glaze, base matte - Learn more

Details

A base glaze is one having no opacifiers, variegators or colorants. Thus it should be transparent if glossy and translucent if matte. Developing or adapting a base glaze to your clay bodies and ware is a very important first step in creating good-quality ware. In fact, it is much better to have a plain base transparent that is functional, durable and adjustable than to have multiple reactive, more visually interesting recipes that are not. The reason for this is that the additives in the latter can be transplanted into the former so that you can have it all!

To melt well enough low temperature glazes need a powerful flux and boron is almost universal. Base clear glazes for low temperatures normally contain high percentages of frit (up to 90%). And of course, at least some is clay to suspend it. Gerstley Borate has historically been used to source boron, but its days are numbered due to mine depletion and frustration with its physical properties. The low thermal expansion of boron also enables much flexibility in adjusting glazes to prevent crazing.

At high temperatures, feldspars, calcium carbonate, dolomite, talc and other natural flux-oxide sources combine with clays and silica to melt very well as a mix (frits are normally not needed). Much higher percentages of silica and alumina are possible so. Unlike lower temperatures, it is less difficult to keep thermal expansion down, crazing is less of an issue. Lower percentages of fluxes (e.g. CaO, Na2O, MgO) also makes it easier to produce base glazes that resist leaching and are more durable. However raw materials (as opposed to frits) produce more gases of decomposition, so it is more difficult to produce crystal clear glazes as transparent as can be done with frits.

Middle temperature is where most potters do their work. More powerful fluxes are needed than for high fire, boron is the principal one used. Gerstley Borate appears very widely in recipes for this reason, but in much lower amounts than low-fire glazes (notwithstanding this cone 6 base clear glazes can have as much as 50%!). But again, frits are the best source of boron. Zinc, lithium and strontium are also employed as auxiliary fluxes. Middle-temperature base glazes, because they have less low expansion SiO2 and Al2O3, can be prone to crazing, especially where high levels of feldspar are present (which is very common). It can be tricky to find a balance that produces a glaze of low enough expansion that still melts well, this underscores the importance of valuing a base recipe once you find one.

Once you achieve a stable, middle-of-the-road transparent base glaze then add an opacifier to get white. Then add stains for color. Of course, while everyone needs quality functional liner glazes, such bases do not easily produce the more interesting variegated surfaces. It is also good to have a fluid melt base, variegators and colors dance more within it (of course, experience is needed to learn how to apply such glazes so they do not run off ware onto the kiln shelves).

Once you have actual base recipe(s) that are working the next challenge is to turn them into a slurry that works well. It is good to be aware of the difference between dipping glazes, brushing glazes and first-coat dipping glazes, then mix them for what you need.

A well-documented testing program to understand how to adjust your base glaze will be one of the best investments in time you can make for your ceramic production. If you are a potter try to develop a mindset that the risk of losing ware in testing is worth the reward of better glazes.

Related Information

Glaze recipes online waiting for a victim to try them!

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

You found some recipes. Their photos looked great, you bought $500 of materials to try them, but none worked! Why? Consider these recipes. Many have 50+% feldspar/Cornwall/nepheline (with little dolomite or talc to counteract their high thermal expansion, they will craze). Many are high in Gerstley Borate (it will turn the slurry into a bucket of jelly, cause crawling). Others waste high percentages of expensive tin, lithium and cobalt in crappy base recipes. Metal carbonates in some encourage blistering. Some melt too much and run onto the kiln shelf. Some contain almost no clay (they will settle like a rock in the bucket). A better way? Find, or develop, fritted, stable base transparent glossy and matte base recipes that fit your body, have good slurry properties, resist leaching and cutlery marking. Identify the mechanisms (colorants, opacifiers and variegators) in a recipe you want to try and transplant these into your own base (or mix of bases). And use stains for color (instead of metal oxides).

A good base glaze, a vitreous clay and a good fit. How good that is!

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Left: Cone 10R buff stoneware with a silky transparent Ravenscrag glaze. Right: Cone 6 Polar Ice translucent porcelain with G2916F transparent glaze. What do these two have in common? Much effort was put into building these two base glazes (to which colors, variegators, opacifiers can be added) so that they fire to a durable, non-marking surface and have good working properties during production. They also fit, each of these mugs survives a boil:ice water thermal shock without crazing (BWIW test). And the clays? These are vitreous and strong. So these pieces will survive many years of use.

In pursuit of a reactive cone 6 base that I can live with

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

These GLFL tests and GBMF tests for melt-flow compare 6 unconventionally fluxed glazes with a traditional cone 6 moderately boron fluxed (+soda/calcia/magnesia) base (far left Plainsman G2926B). The objective is to achieve higher melt fluidity for a more brilliant surface and for more reactive response with colorant and variegator additions (with awareness of downsides of this). Classified by most active fluxes they are:

G3814 - Moderate zinc, no boron

G2938 - High-soda+lithia+strontium

G3808 - High boron+soda (Gerstley Borate based)

G3808A - 3808 chemistry sourced from frits

G3813 - Boron+zinc+lithia

G3806B - Soda+zinc+strontium+boron (mixed oxide effect)

This series of tests was done to choose a recipe, that while more fluid, will have a minimum of the problems associated with such (e.g. crazing, blistering, low run volatility, susceptibility to leaching). As a final step the recipe will be adjusted as needed. We eventually evolved the G3806B, after many iterations settled on G3806E or G3806F as best for now.

Organized testing of stains in a base recipe

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

A quick and organized method of testing many different stains in a base glaze: Prepare your work area like this. Measure the water content of the base glaze as a percent (weight, dry it, weight it again: %=wet-dry/wet*100). Apply labels to the jars (bottom) showing the host glaze name, stain number and percentage added. Counterbalance a jar on the scale, fill it to the desired depth, note the amount of glaze and calculate the weight of dry powder that is present in the jar (from the above %). For each jar (bottom) multiply the percent of stain needed by the dry glaze weight / 100. Then weigh that and add to the jar and put the lid back on. Let them sit for a while, then shake and mix each (I use an Oster kitchen mixer). Then dip the samples, write the needed info on them and fire.

Mason stains in the G2926B base glaze at cone 6

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

This glaze, G2926B, is our main glossy base recipe. Stains are a much better choice for coloring it than raw metal oxides. Other than the great colors they produce here, there are a number of things worth noticing. Stains are potent; the percentages needed are normally much less than for metal oxides. Staining a transparent glaze produces a transparent color, it is more intense where the laydown is thicker - this is often desirable in highlighting contours and designs. For pastel shades, add an opacifier (e.g. 5-10% Zircopax, more stain might be needed to maintain the color intensity). The chrome-tin maroon 6006 does not develop well in this base (alternatives are G2916F or G1214M). The 6020 manganese alumina pink is also not developing here (it is a body stain). Caution is required with inclusion stains (like #6021). Bubbling, as is happening here, is common - this can be mitigated by adding 1-2% Zircopax. And it’s easy to turn any of these into brushing or dipping glazes.

Mason stains in the G2934 matte base glaze at cone 6

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Stains can work surprisingly well in matte base glazes like the DIY G2934 recipe. The glass is less transparent and so varying thicknesses do not produce as much variation in tint as glossy bases do. Notice how low many of the stain percentages are here, yet most of the colors are bright. We tested 6600, 6350, 6300, 6021 and 6404 overnight in lemon juice, they all passed leach-free. The 6385 is an error, it should be purple (that being said, do not use it, it is ugly in this base). And chrome-tin pink and maroon stains do not develop the color (e.g. 6006). But our G1214Z1 CaO-matte comes to the rescue, it both works better with some stains and has a more crystal matte surface. The degree-of-matteness of both can be tuned by cooling speed and blending in some G2926B glossy base. You can mix any of these into brushing or dipping glazes.

An ultra-clear brilliantly-glossy cone 6 clear base glaze? Yes!

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

I am comparing 6 well known cone 6 fluid melt base glazes and have found some surprising things. The top row are 10 gram GBMF test balls of each melted down onto a tile to demonstrate melt fluidity and bubble populations. Second, third, fourth rows show them on porcelain, buff, brown stonewares. The first column is a typical cone 6 boron-fluxed clear. The others add strontium, lithium and zinc or super-size the boron. They have more glassy smooth surfaces, less bubbles and would should give brilliant colors and reactive visual effects. The cost? They settle, crack, dust, gel, run during firing, craze or risk leaching. Out of this work came the G3806E and G3806F.

How do you turn a transparent glaze into a white?

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Right: Ravenscrag GR6-A transparent base glaze. Left: It has been opacified (turned opaque) by adding 10% Zircopax. This opacification mechanism can be transplanted into almost any transparent glaze. It can also be employed in colored transparents, it will convert their coloration to a pastel shade, lightening it. Zircon works well in oxidation and reduction. Tin oxide is another opacifier, it is much more expensive and only works in oxidation firing.

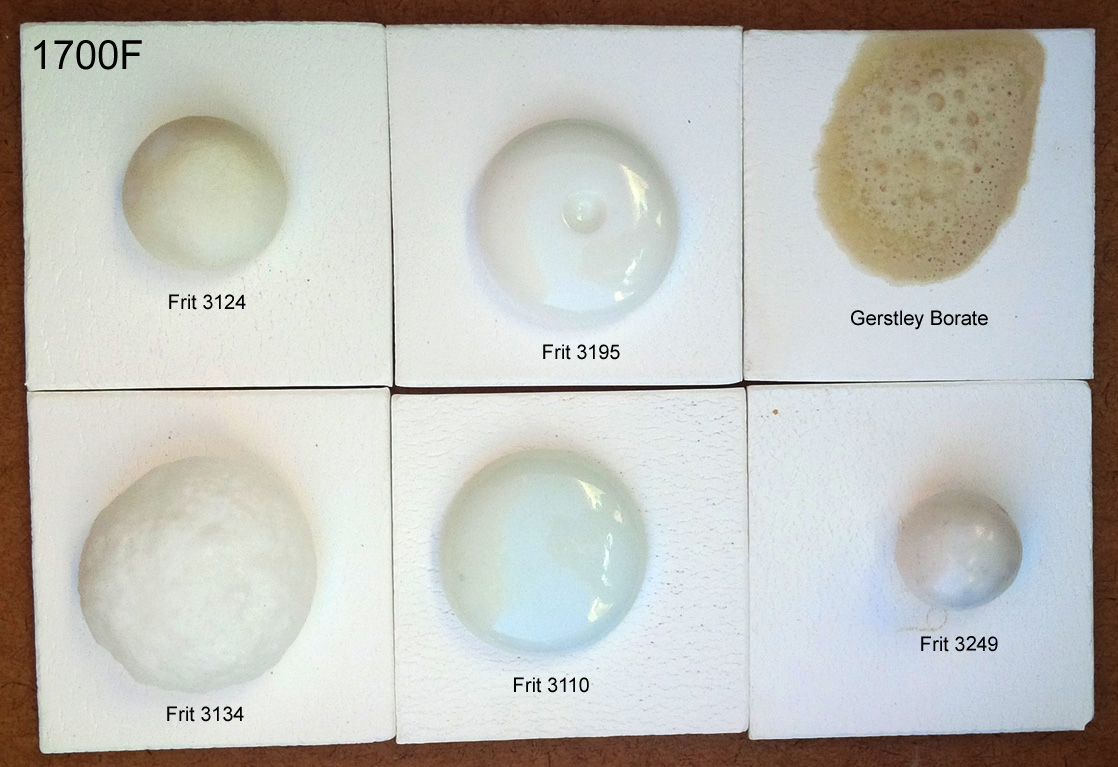

These common Ferro frits have distinct uses in traditional ceramics

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

I used Veegum to form 10 gram GBMF test balls and fired them at cone 08 (1700F). Frits melt really well, they do have an LOI like raw materials. These contain boron (B2O3), it is a low expansion super-melter that raw materials don’t have. Frit 3124 (glossy) and 3195 (silky matte) are balanced-chemistry bases (just add 10-15% kaolin for a cone 04 glaze, or more silica+kaolin to go higher). Consider Frit 3110 a man-made low-Al2O3 super feldspar. Its high-sodium makes it high thermal expansion. It works really well in bodies and is great to make glazes that craze. The high-MgO Frit 3249 (made for the abrasives industry) has a very-low expansion, it is great for fixing crazing glazes. Frit 3134 is similar to 3124 but without Al2O3. Use it where the glaze does not need more Al2O3 (e.g. already has enough clay). It is no accident that these are used by potters in North America, they complement each other well (equivalents are made around the world by others). The Gerstley Borate is a natural source of boron (with issues frits do not have).

Brush-on commercial pottery glazes are perfect? Not quite!

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Brushing glazes are great sometimes. But they would be even greater if the recipe was available. Then it would be possible to make it if they decide to discontinue the product. Or if your retailer does not have it. Or to make a dipping glaze version for all the times when that is the better way to apply. The glaze manufacturer did not consider glaze fit with your clay body, if they work well together it is by accident. But if you have transparent and matte base recipes that that work on your clay body then adding stains, variegators and opacifiers is easy. And making a brushing glaze version of any of them. Don't have base recipes??? Let's get started developing them with an account at insight-live.com (and the know-how you will find there)!

Two base clear glazes with 2% copper:

One is bubbling and one is not.

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

By itself, without copper, the G2926B recipe (right) produces a better and more durable glass (comparing the cups in the back). But a 2% copper addition, front, turns its surface to a mass of unhealed bubble-escapes. The G3808A recipe, on the left, develops much more melt fluidity, the extra mobility enables the bubbles, created by the decomposing copper, to coalesce, grow, break at the surface and heal before the melt stiffens too much.

What can you do using glaze chemistry? More than you think!

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

There is a direct relationship between the way ceramic glazes fire and their chemistry. These green panels in my Insight-live account compare two glaze recipes: A glossy and matte. Grasping their simple chemistry mechanisms is a first step to getting control of your glazes. To fixing problems like crazing, blistering, pinholing, settling, gelling, clouding, leaching, crawling, marking, scratching, powdering. To substituting frits or incorporating available, better or cheaper materials while maintaining the same chemistry. To adjusting melting temperature, gloss, surface character, color. And identifying weaknesses in glazes to avoid problems. And to creating and optimizing base glazes to work with difficult colors or stains and for special effects dependent on opacification, crystallization or variegation. And even to creating glazes from scratch and using your own native materials in the highest possible percentage.

Here is what happens if you do not sieve your glazes when needed

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

This is a cone 6 transparent base glaze. It contains frit, silica, kaolin, wollastonite. Almost all glazes have materials that are slightly soluble and over time these can form scale on the sides of the bucket or even precipitate particles into the slurry. The defects here are those scales. Before dipping a production piece in any glaze that has been in storage it is a good idea to assess it first to see if it needs to be sieved.

Commercial glazes on decorative surfaces, your own on food surfaces

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

These cone 6 porcelain mugs are hybrid. Three coats of a commercial glaze painted on the outside (Amaco PC-30) and my own liner glaze, G2926B, poured in and out on the inside. When commercial glazes (made by one company) fit a stoneware or porcelain (made by another company) it is by accident, neither company designed for the other! For inside food surfaces make or mix a liner glaze already proven to fit your clay body, one that sanity-checks well (as a dipping glaze or a brushing glaze). In your own recipes you can use quality materials that you know deliver no toxic compounds to the glass and that are proportioned to deliver a balanced chemistry. Read and watch our liner glazing step-by-step and liner glazing video for details on how to make glazes meet at the rim like this.

Inbound Photo Links

Links

| Glossary |

Reactive Glazes

In ceramics, reactive glazes have variegated surfaces that are a product of more melt fluidity and the presence of opacifiers, crystallizers and phase changers. |

| Glossary |

Opacifier

Glaze opacity refers to the degree to which it is opaque. Opacifiers are powders added to transparent ceramic glazes to make them opaque. |

| Glossary |

Crystallization

Ceramic glazes form crystals on cooling if the chemistry is right and the rate of cool is slow enough to permit molecular movement to the preferred orientation. |

| Glossary |

Frit

Frits are used in ceramic glazes for a wide range of reasons. They are man-made glass powders of controlled chemistry with many advantages over raw materials. |

| Glossary |

Boron Frit

Most ceramic glazes contain B2O3 as the main melter. This oxide is supplied by great variety of frits, thousands of which are available around the world. |

| Glossary |

Liner Glaze

Liner-glazing is a way to assure that your ware has a durable and leach resistant surface. It also signals to customers that you care about this. |

| Glossary |

Variegation

Ceramic glaze variegation refers to its visual character. This is an overview of the various mechanisms to make glazes dance with color, crystals, highlights, speckles, rivulets, etc. |

| Articles |

Concentrate on One Good Glaze

It is better to understand and have control of one good base glaze than be at the mercy of dozens of imported recipes that do not work. There is a lot more to being a good glaze than fired appearance. |

| Articles |

Reducing the Firing Temperature of a Glaze From Cone 10 to 6

Moving a cone 10 high temperature glaze down to cone 5-6 can require major surgery on the recipe or the transplantation of the color and surface mechanisms into a similar cone 6 base glaze. |

| Articles |

Trafficking in Glaze Recipes

The trade is glaze recipes has spawned generations of potters going up blind alleys trying recipes that don't work and living with ones that are much more trouble than they are worth. It is time to leave this behind and take control. |

| Articles |

Where do I start in understanding glazes?

Break your addiction to online recipes that don't work or bottled expensive glazes that you could DIY. Learn why glazes fire as they do. Why each material is used. How to create perfect dipping and brushing properties. Even some chemistry. |

| Recipes |

G2571A - Cone 10 Silky Dolomite Matte glaze

A cone 10R dolomite matte having a pleasant silky surface, it does not cutlery mark, stain or craze on common bodies |

| Recipes |

G1947U - Cone 10 Glossy transparent glaze

Reliable widely used glaze for cone 10 porcelains and whitewares. The original recipe was developed from a glaze used for porcelain insulators. |

| Recipes |

G2934 - Matte Glaze Base for Cone 6

A base MgO matte glaze recipe fires to a hard utilitarian surface and has very good working properties. Blend in the glossy if it is too matte. |

| Recipes |

G3806C - Cone 6 Clear Fluid-Melt transparent glaze

A base fluid-melt glaze recipe developed by Tony Hansen. With colorant additions it forms reactive melts that variegate and run. It is more resistant to crazing than others. |

| Recipes |

G2926B - Cone 6 Whiteware/Porcelain transparent glaze

A base transparent glaze recipe created by Tony Hansen, it fires high gloss and ultra clear with low melt mobility. |

| Recipes |

G1916Q - Low Fire Highly-Expansion-Adjustable Transparent

An expansion-adjustable cone 04 transparent glaze made using three common Ferro frits (low and high expansion), it produces an easy-to-use slurry. |

| Recipes |

G3879 - Cone 04 Transparent Low-Expansion transparent glaze

A super transparent low fire base clear glaze created by reverse engineering a commercial product. |

| By Tony Hansen Follow me on        |  |

Got a Question?

Buy me a coffee and we can talk

https://digitalfire.com, All Rights Reserved

Privacy Policy