| Monthly Tech-Tip | No tracking! No ads! |

Vitreous

The fired state of a ceramic when sufficient heat in the kiln has produced the density and strength common, and expected, in stonewares and porcelains.

Key phrases linking here: 0, 1 - Learn more

Details

The term "vitreous" refers to a state (whereas vitrification is a process). Vitreous unglazed ceramic surfaces are generally non-staining, non-absorbent. But they are not glassy smooth. Glass is homogeneous, totally dense without a single visible air bubble or pore. But glass is not "vitreous", this term is normally reserved for ceramics, objects that can be fired in a kiln yet maintain their shape without supports. Stonewares and porcelains are most commonly called vitreous. Each body has a temperature at which it is fired to the point of maximum practical density and strength. Fired higher than that pieces begin to warp excessively, surfaces blister and bubbles grow from within (called bloating). Ware fired too high often becomes more brittle to breakage when in use. As clays are heated to increasing temperatures they shrink more and more (e.g. porcelains up to 10%). That shrinkage in accompanied by increasing densification (using the SHAB test we can measure the porosity of a fired ceramic). When percentage porosity is plotted against firing temperature, the line drops toward the x-axis in an increasingly steep curve until it reaches a minimum. It levels there for a time, then, as the clay begins to over-fire, the line veers upward. Typically, the point at which the body is vitreous occurs shortly after that curve reaches the lowest y-value (for porcelains that is almost always zero). The curve can flatten across a fairly wide range for some bodies, somewhere along the flat ware will begin to warp and it is not practical to fire higher.

Vitreous bodies have a micro-structure that can be studied by slicing fired pieces with a diamond saw, polishing the cut surface and examining it under a microscope. These studies reveal that vitreous ceramic matrixes are complex, crystal species evolve with time and temperature often producing a mesh of mineral fibers growing between aggregates of quartz particles all glued together by feldspar glass. This microstructure produces some of the most durable surfaces humans are able to make. When ware is fired beyond the range where the crystals can survive (well into the flat of the curve or beyond that) the integrity of the microstructure degrades.

Related Information

How to decide what temperature to fire this clay at?

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

This is an extreme example of firing a clay at many temperatures to get wide-angle view of it. These SHAB test bars characterize a terra cotta body, L4170B. While it has a wide firing range its "practical firing window" is much narrower than these fired bars and graph suggest. On paper, cone 5 hits zero porosity. And, in-hand, the bar feels like a porcelain. But ware warps during firing and transparent glazes will be completely clouded with bubbles (when pieces are glazed inside and out). What about cone 3? Its numbers put it in stoneware territory, watertight. But decomposition gases still bubble glazes! Cone 2? Much better, it has below 4% porosity (any fitted glaze will make it water-tight), below 6% fired shrinkage, still very strong. But there are still issues: Accidental overfiring drastically darkens the color. Low-fire commercial glazes may not work at cone 2. How about cone 02? This is a sweet spot. This body has only 6% porosity (compared to the 11% of cone 04). Most low-fire cone 06-04 glazes are still fine at cone 02. And glaze bubble-clouding is minimal. What if you must fire this at cone 04? Pieces will be "sponges" with 11% porosity, shrinking only 2% (for low density, poor strength). There is another advantage of firing as high as possible: Glazes and engobes bond better. As an example of a low-fire transparent base that works fine on this up to cone 2: G1916Q.

A terra cotta clay fired from cone 06 (bottom) to 4

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Terra cotta clays mature rapidly over a narrow range of temperatures, showing dramatic changes in fired color, density and strength. These Plainsman BGP SHAB test bars are fired (bottom to top) at cone 06, 04, 03, 02, 2 and 4. At cone 06 (1830F/1000C) it is porous and shrinks very little. But as it approaches and passes cone 03 (1950F/1070C) the color deepens and then moves toward brown at cone 02 (where it reaches maximum density and strength). However, past cone 02 it becomes unstable, beginning to melt (as indicated by negative shrinkage). The second bar up, cone 04, is a good compromise: Adequate strength, good color and low shrinkage. This “single suitable temperature” is completely different than white burning low fire bodies, they are refractory.

A good base glaze, a vitreous clay and a good fit. How good that is!

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Left: Cone 10R buff stoneware with a silky transparent Ravenscrag glaze. Right: Cone 6 Polar Ice translucent porcelain with G2916F transparent glaze. What do these two have in common? Much effort was put into building these two base glazes (to which colors, variegators, opacifiers can be added) so that they fire to a durable, non-marking surface and have good working properties during production. They also fit, each of these mugs survives a boil:ice water thermal shock without crazing (BWIW test). And the clays? These are vitreous and strong. So these pieces will survive many years of use.

How much does a porcelain piece shrink on firing?

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Left: Dry mug. Right: Glazed and fired to cone 6. This is Polar Ice porcelain from Plainsman Clays. It is very vitreous and has the highest fired shrinkage of any body they make (14-15% total). This is the highest firing shrinkage you should ever normally encounter with a pottery clay.

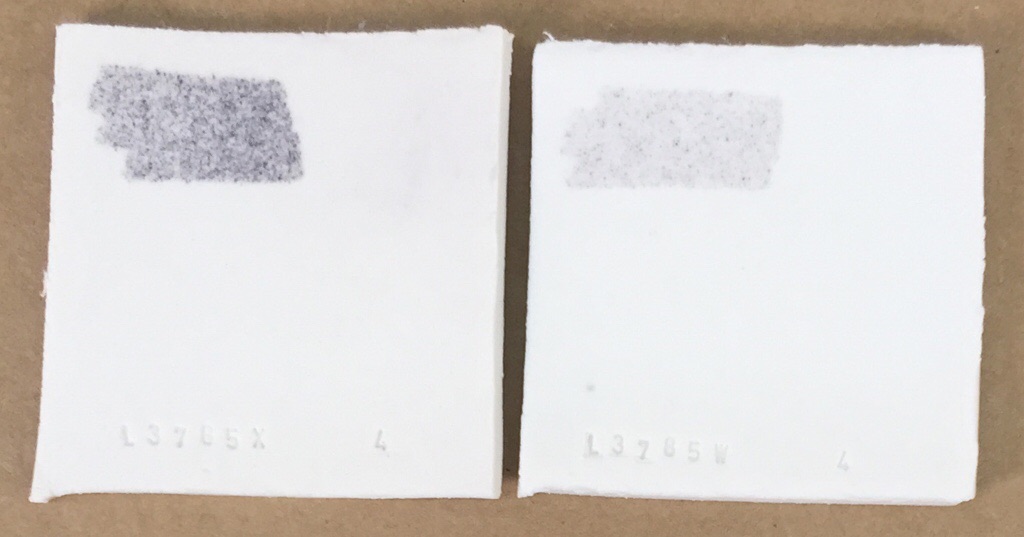

A novel way to compare degree of porcelain vitrification

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

These two unglazed porcelain tiles appear to have a similar degree of vitrification, but do they? I have stained both with a black marker pen and then cleaned it off using acetone. Clearly the one on the right has removed better, that means the surface is more dense, it is more vitreous. In industry (e.g. porcelain insulators) it is common to observe the depth of penetration of dye or ink into the matrix as an indication of fired maturity.

A non-vitreous body can have a very poor bond with the glaze

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

This glaze is on very thick. That gives it the power to impose its thermal expansion (which is different that the body) to the point where it literally flakes off. The problem is worsened when the glaze and body lack fluxes, that means they do not interact, no glassy interface is formed.

Links

| Glossary |

Porcelain

How do you make porcelain? There is a surprisingly simple logic to formulating them and to adjusting their working, drying, glazing and firing properties for different purposes. |

| Glossary |

Stoneware

To potters, stonewares are simply high temperature, non-white bodies fired to sufficient density to make functional ware that is strong and durable. |

| Glossary |

Porcelaineous Stoneware

In ceramics, porcelains lack plasticity and fire to high density with white, glassy surface. Stonewares are plastic and fire cream to brown and lower density, Porcelaineous stoneware are between these two. |

| Glossary |

Sintering

A densification process occurring within a ceramic kiln. With increasing temperatures particles pack tighter and tighter together, bonding more and more into a stronger and stronger matrix. |

| Glossary |

Vitrification

A process that happens in a kiln, the heat and atmosphere mature and develop the clay body until it reaches a density sufficient to impart the level of strength and durability required for the intended purpose. Most often this state is reached near zero p |

| By Tony Hansen Follow me on        |  |

Got a Question?

Buy me a coffee and we can talk

https://digitalfire.com, All Rights Reserved

Privacy Policy