| Monthly Tech-Tip | Feb 14-15, 2026 - Major Server Upgrade Done | No tracking! No ads! |

Viscosity

In ceramic slurries (especially casting slips, but also glazes) the degree of fluidity of the suspension is important to its performance.

Key phrases linking here: viscosity - Learn more

Details

The term viscosity is used in ceramics most often to refer to the degree of fluidity of a slurry or suspension (the term 'shear' is often used when discussing viscosity, theoretically engineers understand viscosity in terms of layers particles or molecules that exhibit a friction that resists lateral displacement against each other). Viscosity is the opposite of fluidity, a term also commonly used, viscous slurries are thick and thus lack fluidity. Laboratory instruments that measure absolute viscosity (that can be quoted on a data sheet) are called viscometers and they express the result in a unit called the poise. Higher poise numbers mean a more viscous slurry. Units of fluidy are taken as 1/poise, thus 2 poise = 0.5 rhe (water has a fluidity of 100 rhe). However much simpler devices can also be practical for quality control and comparative studies (e.g. a Ford Cup used for paint simply times the drain of a liquid through a small hole in the bottom).

The viscosity of a slurry can be reduced by the addition of a deflocculant, fluid slurries of remarkably low water content can be produced. Deflocculants work their magic by imparting electrical charges to the surfaces of particles to make them repel each other. Conversely, the viscosity of a slurry can be increased by the addition of a flocculant that makes it gel (if its specific gravity is high enough). Soluble materials within a powdered mix can impede or block the action of deflocculants and particle properties like size, size distribution, shape, surface area, surface reactivity, density, etc. all affect their action. See the Potters Dictionary under Fluidity for a detailed and easy-to-understand discussion of this (especially relating to the dynamics imparted by flat particles with differing end and flats charges).

Controlling the viscosity of casting slips is vital for efficient production. However, it is critical that the correct specific gravity first be achieved, then it becomes apparent if more or less deflocculant is needed. Ideally, a slurry needs to be thin enough to pour and drain easily, but thixotropic enough to form a gel after some time (e.g. 1/2 hour) to prevent settling. Generally it is best to slowly introduce measuring devices as part of quality control - rely on physical observation and experience during early adoption of new recipes.

Viscosity of dipping glazes is an important factor in their performance. It seems obvious that ones of high viscosity will apply thicker to ware and vice versa. However, like casting slips, viscosity must be considered in consort with the specific gravity (and thixotropy). For typical bisque fired pottery a raw or partially fritted dipping glaze works well at a specific gravity of about 1.45 (taking it too much higher could lead to settling, too thick application, tendency to drip, etc). Vinegar or Epsom salts can be added to increase the viscosity to that which works best (gives an even layer of glaze on a fairly quick dip).

Molten glazes also exhibit viscosity, but the term 'fluidity' is normally used.

Related Information

Confirming slip viscosity using a paint-measuring device

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

A Ford Cup is being using to measure the viscosity of a casting slip. These are available at paint supply stores. This is a #4 (4.25mm opening), it holds 100ml and drains water in 10 seconds. This casting slip has a specific gravity of 1.79. Having made it many times, our experience indicates 40-seconds as a drain target (after high energy mixing). In production situations, the seconds-value this test produces enables an audit-trail for quality control and problem solving. When first mixing a slurry, under-deflocculating and eye-balling the viscosity is typical, during that period the slurry gels while draining and Ford cup measurements are not valid. When the mixing process has been perfected and viscosity stabilized the Ford Cup becomes practical.

Don’t overthink this type of measurement or the type of cup or opening size (you can even make your own cup). You must still determine the optimal flow rate based on experience with your process. This technique is more about maintaining to ongoing adherence to a standard you define.

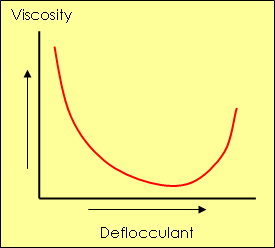

A viscosity deflocculation curve

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

As the amount of defloccuant is increased the viscosity drops and the slurry becomes more and more fluid. However, at some point, the slurry will begin to become more viscous with increasing deflocculant percentages. This underscores the importance of tuning your casting slip recipes to avoid this problem. It is actually better to deflocculate to a point before the curve reaches its minimum (where the slope is still downward). This "controlled state of flocculation" enables the slip to gel after a period of time (to prevent sedimentation) and avoids the issues that come with over-deflocculation.

Links

| Articles |

A Low Cost Tester of Glaze Melt Fluidity

Use this novel device to compare the melt fluidity of glazes and materials. Simple physical observations of the results provide a better understanding of the fired properties of your glaze (and problems you did not see before). |

| Articles |

Understanding the Deflocculation Process in Slip Casting

Understanding the magic of deflocculation and how to measure specific gravity and viscosity, and how to interpret the results of these tests to adjust the slip, these are the key to controlling a casting process. |

| Glossary |

Deflocculation

Deflocculation is the magic behind the ceramic casting process, it enables slurries having impossibly low water contents and ware having amazingly low drying shrinkage |

| Glossary |

Melt Fluidity

Ceramic glazes melt and flow according to their chemistry, particle size and mineralogy. Observing and measuring the nature and amount of flow is important in understanding them. |

| Glossary |

Thixotropy

Thixotropy is a property of ceramic slurries of high water content. Thixotropic suspensions flow when moving but gel after sitting (for a few moments more depending on application). This phenomenon is helpful in getting even, drip-free glaze coverage. |

| Glossary |

Water in Ceramics

Water is the most important ceramic material, it is present every body, glaze or engobe and either the enabler or a participant in almost every ceramic process and phenomena. |

| Glossary |

Specific gravity

In ceramics, the specific gravity of slurries tells us their water-to-solids ratio. That ratio is a key indicator of performance and enabler of consistency. |

| Glossary |

Spray Glazing

In ceramic industry glazes are often sprayed, especially in sanitary ware. The technique is important. |

| Glossary |

Ceramic Glaze Defects

Ceramic glaze defects include things like pinholes, blisters, crazing, shivering, leaching, crawling, cutlery marking, clouding and color problems. |

| URLs |

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Viscosity

Viscosity at Wikipedia |

| URLs |

http://www.viscosityjournal.com

ViscosityJournal.com |

| URLs |

https://www.smac.it/en/dettaglio.php?idprod=226

V-Check glaze slurry viscosity monitoring device Monitors the viscosity of the glaze delivered by the tank pump and signals by alarm values exceeding the tolerance range set by the operator. |

| Tests |

Rheology of a Ceramic Slurry

|

| Tests |

Apparent Viscosity (cps)

|

| Troubles |

Uneven Glaze Coverage

The secret to getting event glaze coverage lies in understanding how to make thixotropy, specific gravity and viscosity work for you |

| Media |

Thixotropy and How to Gel a Ceramic Glaze

I will show you why thixotropy is so important. Glazes that you have never been able to suspend or apply evenly will work beautifully. |

| By Tony Hansen Follow me on        |  |

Got a Question?

Buy me a coffee and we can talk

https://digitalfire.com, All Rights Reserved

Privacy Policy