Notes

Vanderbilt Minerals describes Veegum T and R as "Magnesium Aluminum Silicates, water-washed white-firing smectite clays, used as a suspending agents for glazes, as plasticizing agents for nonplastic formulations such as high alumina, zirconia and porcelain bodies, and as a nonmigrating binder in extruded bodies." They do not provide a chemistry, but usually, the percentages used in recipes are very small anyway. When the term "Veegum" is used in ceramics it generally refers to Veegum T or Veegum R.

On this site we often refer to Veegum in a general sense, meaning that other highly refined bentonite, smectites, hectorites, attapulgites, etc. might also be suitable in your application. Veegum is the one we have most experience with. It has an unfortunate name, it is not a gum, that is, a hardening agent. It is a gelling agent.

Veegum, or Veegum R (less purified) and VeeGum T (or VGT) are not 'gums', rather they are a refined fine particle mineral called 'smectite' (bentonite and hectorite are members of the smectite group, smectite is CAS 12199-37-0, bentonite is CAS 1302-78-9). It is a complex colloid and extremely plastic and sticky magnesium aluminum silicate (CAS 1327-43-1). It is an off-white insoluble flaky consistency and swells to many times its original volume when added to water. Its aqueous dispersions are thus high viscosity thixotropic gels at low solids. A potter encounters this phenomenon when employing significant percentages of VGT in glazes and porcelain bodies (e.g. more than 2%), finding that much more water is needed to produce a pourable suspension (meaning the low specific gravity suspensions can be thickened). Veegum is not subject to attack by microorganisms. Various grades are classified according to viscosity and ratio of aluminum to magnesium content.

Veegum T is the highly purified, whitest grade. It is recommended for pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, and food where purity, low heavy metals, and low microbiological counts are critical. Very effective at swelling, suspending, and thickening aqueous systems.

Veegum R is a technical grade of the same material, intended for industrial uses (ceramics, adhesives, paints, coatings, etc.). Less purification, so it can be slightly darker or contain minor impurities not acceptable in pharma/food. Functions the same way (hydrating, swelling, suspending), but specifications are looser. It is much less expensive.

It is important to properly hydrate the powder, mix it in water before adding other ingredients (different grades of Veegum hydrate at different rates). They emphasize not underestimating the time needed, pointing out that in 25C water it could take 120 minutes using a propeller mixer! Using hot water or a higher-energy mixer can drastically cut the time needed. If mixing does not hydrate all particles, then variations in mixing will produce variations in properties, so use the same water temperature, mixing time and energy and viscosity each time it is used to get consistent behavior in the slurry or pugged material.

In glazes, Veegum is used as an invaluable in-mix suspending agent and thickener (enabling low specific gravities). This is especially important in brushing glazes where high water content is important to brushing properties. For such, a Veegum addition is a way to thicken yet still suspend a glaze slurry that would otherwise be thin-as-water (see info on Veegum CER below). Note that if, over time and brushing glaze slurry thins and settles, the likely culprit is microbial attack on the organic gum as likely in the recipe.

It can also be suitable for use as a spray-on surface hardener before decorating (mix it with water, start with 0.2% for testing).

In bodies, Veegum is employed as a plasticizing agent. It is a nonmigrating binder because it is not dissolved in the water. Its key advantage is that it is clean and therefore does not affect fired whiteness. 1.5-2.0% added to a porcelain, that is otherwise a little too short for modelling or throwing, will transform it into a plastic material. Amazingly, VGT can plasticize completely nonplastic materials (such as calcined alumina, zirconia, calcium carbonate, magnesium carbonate, dolomite) at only 3-4%! White-burning porcelains are low-plasticity by nature, but VGT in higher percentages (up to 4%) can produce fantastic plasticity and workability. VGT may produce more plasticity in one body than another, depending on the type of kaolin present and the particle dynamics of the mix. For some formulations, it is difficult to produce the needed plasticity without ending up with a body that is too sticky or requires too much water.

Veegum CER has been discontinued (as of 2025). It was described as a mixture of VEEGUM R and medium viscosity sodium carboxymethylcellulose (CMC gum) that served to harden, suspend and stabilize viscosity in glazes. A maximum viscosity suspension was made using about 45 grams per litre of water (you will need a good propeller mixer and hot water to do this, the gelled solution is easier to scoop out with a spoon, it is much less stringy than CMC Gum solution). A Veegum CER solution can be added to an already-mixed dipping glaze to impart the above properties, although it lowers the specific gravity it also gels the slurry. If enough is added more water will also be needed, in this way, slurries of low specific gravity can be made (e.g. for brushing glazes). You may need to make Veegum CER solutions in smaller quantities or add a biocide (bacterial growth is possible).

Veegum Pro is Veegum T treated with an amine to improve dispersibility. It is recommended for use where a minimum amount of water is required and/or only low-shear mixers are available.

Other grades (like F, HV, K, HS) are used in non-ceramic applications (like pharmaceuticals and personal care products).

In calculations, use the bentonite chemistry (it is possible in INSIGHT to label a recipe line as Veegum yet specify bentonite as the material database lookup value).

Density (Mg/m3): 2.6

Viscosity (after shear mixing, 5% dispersion): 250 cps +/- 25%

Moisture: 8% max

pH: 8.5

The Vanderbilt Minerals website product finder does not work for finding most Veegum grades (as of Sept 2025).

Related Information

Control gel using Veegum, brushing properties with CMC gum

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

This is G1214Z1 brushing glaze (with 5% titanium added). For a 340g powder batch (to get a pint) my initial target is 5g CMC gum and 5g Veegum. CMC controls drying speed and Veegum the amount of gelling. I first mix the CMC with the powder and shake the whole batch in a plastic bag. Then I add it all to 440g of water in the blender jar and mix it well (making sure no agglomerates remain (stage 1). Stage 2 is adding the VeeGum slowly, while high-speed blender-mixing, this is important because it enables tuning the degree of gel (which cannot be predicted). Because this recipe has little clay, it took all 5g of Veegum without overgelling (the entire mass moved freely in the mixer jar). But it did gel overnight (so 4g would be better next time). By contrast, it is the brushing behavior that demonstrates whether the amount of CMC is right. Not enough and coats dry too fast and go on too thick. Too much and it dries too slowly and too many coats are needed.

Veegum is not a gum, it is a gelling agent. CMC gum needs something it provides.

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

On the left, the brush-strokes of gummed glaze, which I batched myself, have been freshly painted onto an already-fired glaze. Notice the brown brush stroke holds its character. It has a high specific gravity (SG): 1.6. And contains 1.5% CMC gum. The white one to its left, whose brush stroke has flattened and it is running downward, has the same gum content but an SG of 1.5. Is it running because of its lower SG? No. Commercial glazes with an SG below 1.3 still hold in place well. How? Because they also have a gelling agent (e.g. Veegum - it has an unfortunate name, it is not a gum). That reveals a secret: Gums and gelling agents need each other. CMC Gum needs particle surface area to work its magic and bentonite, the gelling agent here, supplies that. And, the gelling agent needs the gum to slow down drying and enable a hard and crack-free dried surface. The dried strokes on the right demonstrate that - 2% bentonite has been added to the drippy one on the far left. They held in place because of the bentonite and hardened without cracking because of the CMC gum.

How fast will Veegum settle in water?

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

This is VeeGum T, a processed smectite clay (similar to bentonite, extremely small particle size). I have propeller-mixed enough powder into water that it has begun to gel. How long does it take for them to begin to settle? Never. This sat for a month with no visible change! That means it is colloidal. For ceramic slurries, Veegum is a gelling agent, not a gum (or hardener).

The premium plasticizer has a premium price. Brace yourself.

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

VeeGum T is expensive. Each of these boxes contains a 50 lb bag. You are looking at $6000 worth of material (in 2015)! This is enough to plasticize 450 20 kg boxes of porcelain containing 4% VeeGum. Is it worth it? Yes, this is the king of bentonites, nothing can produce a porcelain body that has the workability and translucency this can impart. Yes, translucifies. Not sure how yet but it does.

Mineral Colloid BP, Gelwhite H, Veegum T in plastic form

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Each has been mixed with water and all produce a jelly-like translucent sticky material that takes a very very long time to dry. They are expensive and, among other uses, act as white-burning plasticizers in fine porcelain bodies.

Veegum T , Mineral Colloid BP, Gelwhite H at cone 6

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

The Veegum is dense and white, but not melting. The Mineral Colloid fires like a typical raw bentonite (dark brown, high soluble salts and beginning to melt). The Gelwhite is completely melted and foamed.

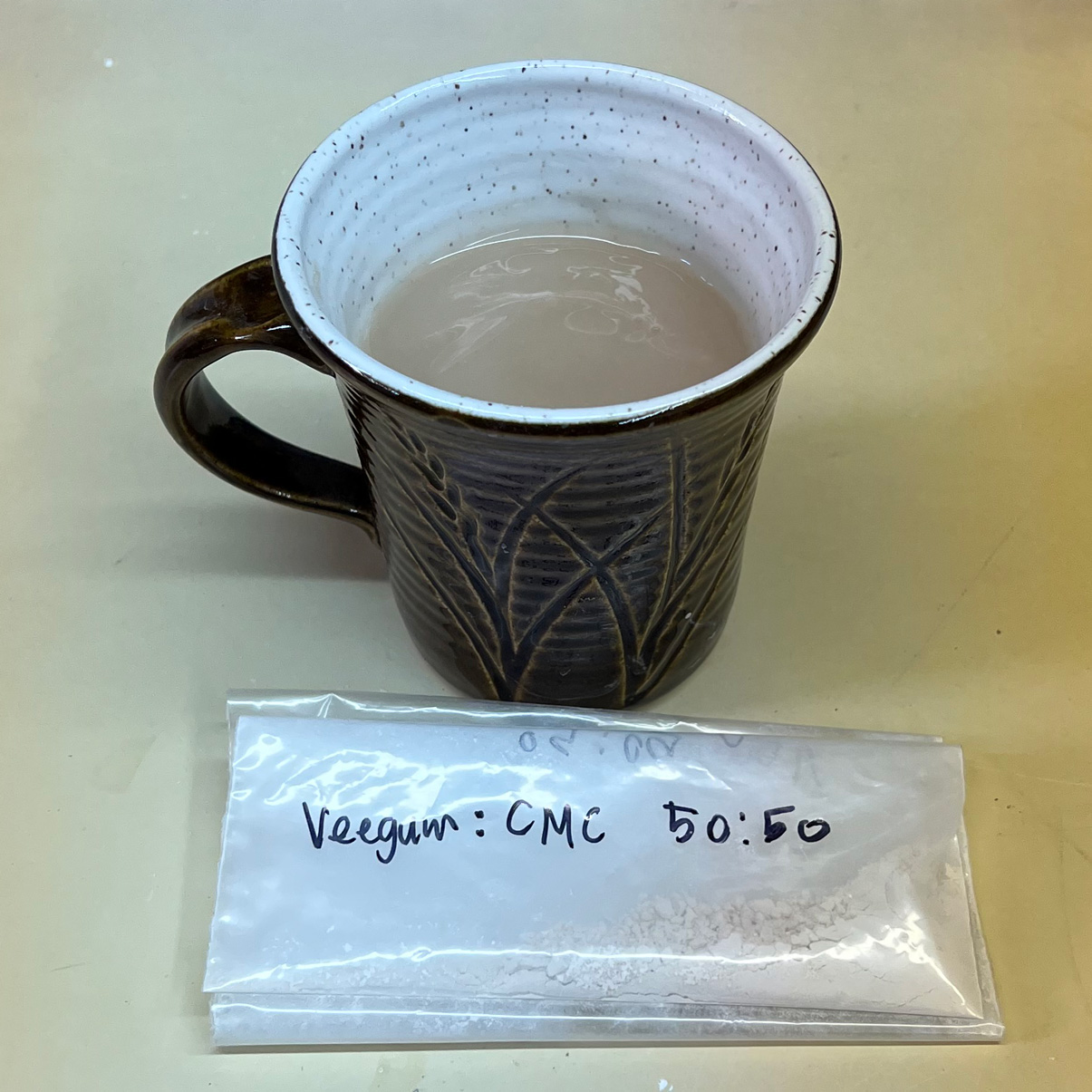

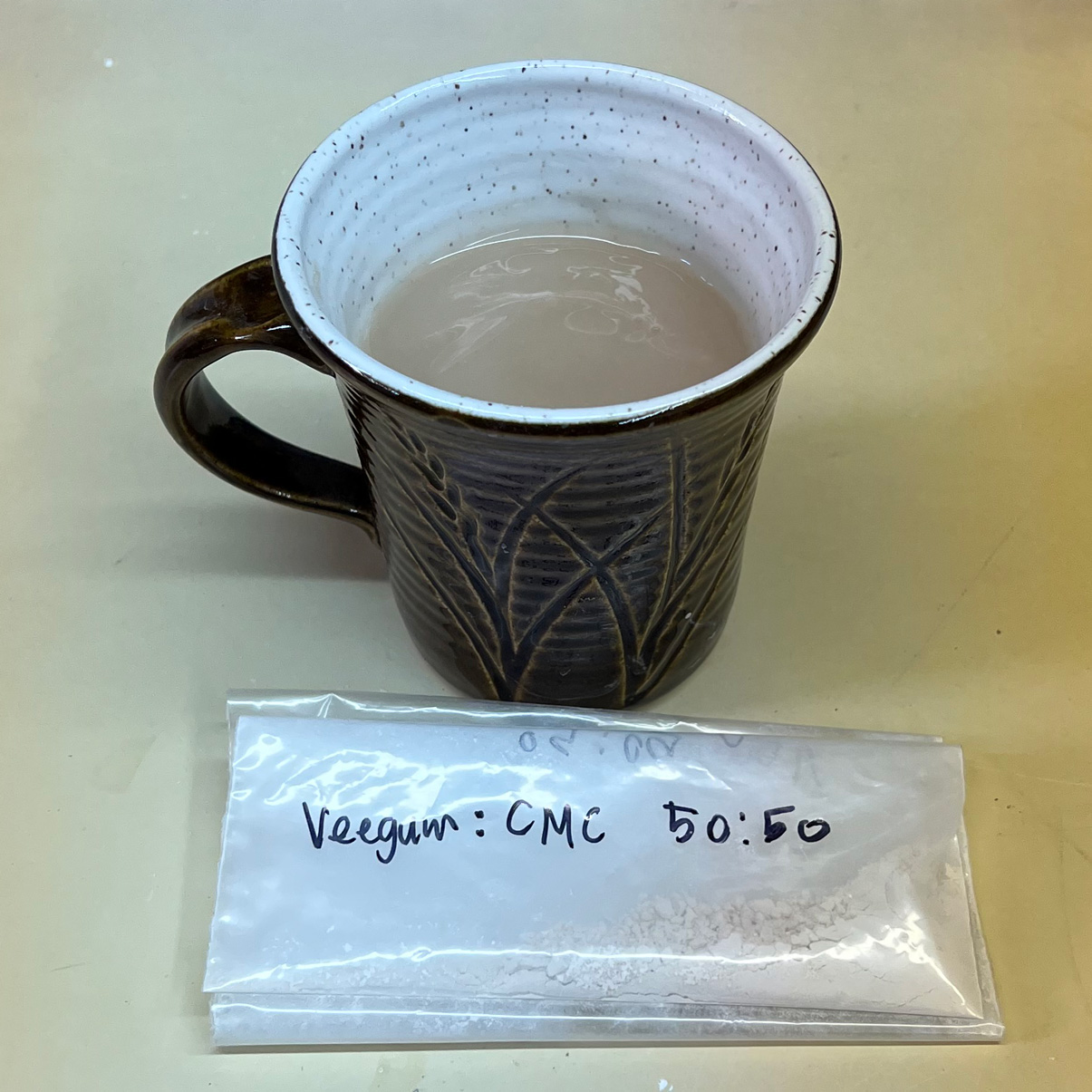

Veegum CER Saturated suspension

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

This is the most viscous suspension we can make using hot water and a propeller mixer - 300ml water with 13.25g Veegum CER. In glazes having low clay content adding this gels the slurry, enabling higher water content to improve its brushing properties and slow down drying. In slurries having plenty of clay pure CMC gum is usually better (unless a high-water-content slurry is needed). Of course, keep in mind that anything with CMC gum can be subject to microbial attack.

You may know Veegum T but do you know VeeGum CER?

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

The glaze in this jar was 'goop', impossible to paint on because it was too viscous. And it dried way too fast. Laguna mentions adding water so I measured the specific gravity (SG): 1.7. That is super-high, it took a 125cc addition to bring it down to 1.5, but it was still thick, dried even faster, and brushing it on evenly was even harder. It was not obvious what to do next. It needed a lot more water (1.3-1.35 SG is normal for multi-layer application of low SG glazes), adding CMC gum and enough water to do that would produce an unusable watery and sticky slurry. Veegum CER to the rescue! It is a 50:50 mix of CMC gum and Veegum T. The former slows drying and hardens, the latter gels. So it can simply be added until the painting properties are right. And, a Veegum CER solution is easier to handle than one of CMC gum. The brushing properties are just right, it gels nicely on standing and stays in place on verticals. CER is also good for highly fritted dipping glazes or others lacking in clay content (otherwise CMC might still be better).

Throw Zircopax on the potters wheel. Just add VeeGum.

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

These crucibles are thrown from a mixture of 97% Zircopax (zirconium silicate) and 3% Veegum T. The consistency of the material is good for rolling and making tiles but is not quite plastic enough to throw very thin (so I would try 4% Veegum next time). It takes alot of time to dewater on a plaster bat. But, these are like nothing I could make from any other material. They are incredibly refractory (fired to cone 10 they look like bisqued porcelain). However I have had mixed results for thermal shock resistance.

10% Veegum porcelain slurry dewatering on plaster

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

It has taken a couple of days to reach this state, it still has a very high water content and needs another day or two of stiffening. This cracking occurs because much more water is needed to thin a slurry enough to be able to propeller-mix it effectively. Typical clays can be dewatered in this manner in a few hours but not this one. By the way, this is fantastically plastic to use on the potters wheel, but high percentages of Veegum like this would not be affordable or practical.

Ridiculously plastic porcelain! How?

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

A ridiculous recipe. I just threw this mug from a porcelain having 10% Veegum plasticizer (of course no one could afford that, it is $15 a pound). But anyway, I was testing the extreme. These mugs did not twist during throwing, I could have pulled the wall thinner at the middle and top. The wall thickness at the bottom is 2.3mm (less than 3/32")! This mug is 15cm (6 in) tall. One problem: It takes forever to dry.

How much VeeGum is needed in a super white porcelain?

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

When formulating a white throwing porcelain that employs a white expensive plasticizer (like Bentone or Veegum) the optimal range of percentages can be surprisingly narrow (I am assuming at least 40% kaolin is present). The trimming behavior is one indicator. When there is insufficient plasticizer the tool will chatter (of course in extreme cases edges will tear). Smoothing the corners after trimming (using your finger) will also give you an indication. If there is too much plasticizer, the material will ball up under your finger, if there is insufficient it will not smooth out well. The percentage can be critical: 0.5% too high and the drying shrinkage could sky rocket, 0.5% too low and lips can split at the rim during throwing.

VeeGum percentage must be precisely tuned in a porcelain

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

This fine white New Zealand porcelain body has to be plasticized using an expensive white bentonite (VeeGum). In this test mix, the percentage of VeeGum was slightly low (3.25%). Although it is very plastic and throws well on the potters wheel, the tendency to split at the rim is evident on this dried mug. Only 0.5% more Veegum is needed to solve this issue. The percentage is critical, enough to eliminate this issue but not too much or the drying shrinkage will be excessive.

VeeGum and CMC gum can plastify non-plastic powders for making melt-flow test balls

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Fluxes used in ceramics are almost always non-plastic, they cannot be formed like clay - frits and feldspars are good examples. And they don't dry hard. To make balls for use in the GBMF test for melt flow a binder needs to be added. Traditionally we have used Veegum, however, it interacts with materials enough to affect melting - CMC gum does not. That being said, Veegum dries better (these balls can dry very slowly). When simply comparing the melt of two materials either is fine.

Each ceramic powder responds differently to being water-mixed with a gum or plasticizer. Some material-gum mixes uptake water so well that it can be worked in drops at a time until a plastic material is produced. Others require vigorous mixing into a slurry and then dewatering on a plaster surface. We target 9g balls, they fit into the reservoir of the melt flow tester. To make one ball we start with 11 or 12g of powder (to allow for waste) and then form them into 12g (wet) balls - these dry them down to the 9g weight. We are almost always comparing the flow of two materials, in these cases it is only important that the two balls be the same weight - so we trim the heavier one down to the weight of the lighter one. Does cornstarch work? No, the mix is not plastic. Psyllium? Yes, but it has a flakey texture and demands more water.

If you are testing a plastic material then a binder is not needed.

The secret of this cone 6 translucency will surprise you!

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Three cone 6 mugs. All have zero porosity. Why is the middle one so translucent? Three reasons.

1. It has 10% more feldspar than the one on the left and reaches zero porosity already at cone 5.

2. It employs New Zealand china clay while the one on the left contains high-TiO2 #6 Tile kaolin.

But this is also true for the one on the right. The third difference is the key.

3. The center one contains 4% Veegum T plasticizer (while the other two use standard bentonite). This is surprising when I tell you one more thing: The mug on the right also contains 3% Ferro Frit 3110. That means that the frit does not have near the fluxing power of the VeeGum!

VeeGum and bentonite in the same porcelain! How can they fire this different?

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

These two cone 10 porcelains have the same recipe. 50% Grolleg Kaolin and 25% each of silica and feldspar. But the one on the left is plasticized using 3.5% VeeGum T and the one on the right uses 5% regular raw bentonite. The VeeGum is obviously doing more than making it more workable, it is acting as a powerful flux and super-catalyst for translucency! Although not clear from this picture, the entire translucent mug is covered with blisters, it has over vitrified. This is another big benefit of VeeGum, its use in a porcelain enables cutting the amount of feldspar significantly (while retaining the translucency). This is good because it permits increasing the kaolin content for plasticity. Or increasing the silica for glaze fit.

The fluxing power of Veegum with pure Nepheline Syenite

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

These fired bars are nepheline syenite (NS) fired to Orton cone 03 (~2000F). The top bar, L4526C, is 95% NS and 5% Veegum. Its porosity is 3%. The bottom bar, L4526B, is 90% NS and 10% raw bentonite. Its porosity is 19%! The top bar has much higher fired shrinkage, it looks and feels like a porcelain, that is clearly what is densifying it so much (the bottom one looks and feels like Plaster of Paris). Veegum is a super white clay plasticizer, not a flux. But it is acting as the latter here. Or perhaps its surface area enables acting as a catalyst to initiate the melting of the nepheline syenite. Don’t think it’s fair to call the top bar a porcelain? A traditional dental porcelain can be 85% feldspar and 5% clay, this has 5% clay also. This has not matured enough to be a glass ceramic either (modern dental porcelains are pure frit glass ceramic).

Covia nepheline syenite demonstrates the incredible fluxing power of Veegum

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

The left bars are 5% Veegum and 95% nepheline syenite. By cone 02 (bar #4) it is self-glazing and glass-like with a total shrinkage (plastic to fired) of 15% (less than some porcelains). At cone 03 (bar #5) the porosity is 3% (a stoneware). The right bars are 10% raw bentonite and 90% nepheline (thus the darker color). The top bar (#1) went to cone 3 and has 20% total shrinkage and zero porosity. The bar below it, #3, has 3% porosity. That means that the vitrification process is 6 cones (115°F) ahead in the Veegum-plasticized material compared to the bentonite-plasticized version. Yet the percentage of Veegum is only half as much! This is clear evidence of how powerful of a flux Veegum is.

Links

| URLs |

https://www.vanderbiltminerals.com/resources/Minerals_and_Chemical_for_Ceramics_and_Refractories_web.pdf

Vanderbilt Minerals for Ceramics Technical Sheet

Includes Vansil, Pyrax, Peerless, Dixie, Veegum, Vanzan, Darvan.

|

| URLs |

https://www.vanderbiltminerals.com/resources/VAN_GEL_VEEGUM_Industrial_Applications_Web.pdf

VEEGUM Magnesium Aluminum Silicate For Industrial Applications

A very detailed technical booklet about Veegum and Van Gel from the manufacturer.

|

| URLs |

https://www.vanderbiltminerals.com/products/veegum-r

Vanderbilt VEEGUM-R data sheet

VEEGUM® R Magnesium Aluminum Silicate is the original and most widely used grade. VEEGUM R is a highly purified smectite clay suspension stabilizer, emulsion optimizer and rheology modifier. It is synergistic with common thickeners such as VANZAN® xanthan gum and CMC. These combinations will provide greater thickening, stabilizing and suspending properties than those developed by the individual components of the mixture.

|

| URLs |

https://www.vanderbiltminerals.com/resources/34108_PYRAX-WA_US_EN_VC-VM.pdf

Vanderbilt Smectite Clays technical data sheet

Compares the properties of, and explains the differences between, Veegum T, Veegum CER, Veegum Pro, Van Gel B, Van Gel SX, VANZAN.

|

| URLs |

https://www.vanderbiltminerals.com/product-finder

Vanderbilt Minerals product finder

|

| Materials |

Bentone MA

|

| Materials |

Bentolite L-3

|

| Materials |

New Zealand Halloysite

The whitest burning kaolin we have ever seen. It is very sticky when wet, suspends glazes well & makes super white porcelain (with help from a white bentonite).

|

| Materials |

Mineral Colloid BP

|

| Materials |

Gelwhite H

|

| Materials |

Bentone EW

|

| Materials |

Magnabrite

|

| Materials |

Hectabrite

White magnesium-rich surface-modified highly purified sodium hectorite clay 4-5 times more efficient than raw bentonite.

|

| Materials |

Hectalite GM

|

| Typecodes |

Additives for Ceramic Glazes

Materials that are added to glazes to impart physical working properties and usually burn away during firing. In industry all glazes, inks and engobes have additives, they are considered essential to control of cohesion, adhesion, suspension, dry hardness, surface leveling, rheology, speed-of-drying, etc. Among potters, it is common for glazes to have zero additives.

|

| Typecodes |

Additives for Ceramic Bodies

Materials that are added to bodies to impart physical working properties and usually burn away during firing. Binders enable bodies with very low or zero clay content to have plasticity and dry hardness, they can give powders flow properties during pressing and impart rheological properties to clay slurries. Among potters however, it is common for bodies to have zero additives.

|

| Minerals |

Smectite

A highly plastic clay mineral related to montmorillonite (bentonite), more correctly, the name of th

|

| Articles |

Binders for Ceramic Bodies

An overview of the major types of organic and inorganic binders used in various different ceramic industries.

|

| Articles |

Formulating a Porcelain

The principles behind formulating a porcelain are quite simple. You just need to know the purpose of each material, a starting recipe and a testing regimen.

|

| Glossary |

Fritware

|

By Tony Hansen

Follow me on

|  |

Got a Question?

Buy me a coffee and we can talk

https://digitalfire.com, All Rights Reserved

Privacy Policy