| Monthly Tech-Tip | Feb 14-15, 2026 - Major Server Upgrade Done | No tracking! No ads! |

Micro Organisms

Ceramic glazes and clay bodies can host micro organisms. They can be just a nuisance, a source of worry or can render a product useless. What should you do?

Key phrases linking here: micro organisms, micro-organisms, anti-microbials, microorganisms, anti-microbial, mold on clay, microbial, microbes, biocide - Learn more

Details

Every potter has had the experience of opening a bucket of glaze only to be met with a foul odour; microorganisms of some sort have grown. Or, open a jar of brushing glaze only to find that it has thinned and does not brush on normally. While it seems odd that they could even have grown in a bucket of water mixed with rock powder, it is an aqueous system and usually, at least some organics are present (e.g. lignite in the clays, CMC gum). The microbials can lessen or neutralize the function of the organic binders in the slurry, thus affecting suspension, application properties and rheology. It follows that fixing the problem will not be as easy as just adding some bleach or Dettol. That may or may not remove the odor, but it won’t fix the damage done. Typically, a glaze like this is ‘terminal’. That is not to say there exists no strategy to correct it, but no one is going to hire a microbiologist to figure out whether it is a bacteria, fungus, mold, algae or yeast and what anti-microbial is needed! Glazes used in industry seldom have this issue and it is not because they are used continuously as made, it is because anti-microbials (biocides) are added when they are mixed. Just like with human health, little is needed to prevent the growth of microorganisms whereas a lot is needed to rescue a slurry once they take hold.

All prepared wet glazes made for pottery and hobby markets contain biocidal additives (the most likely target is bacteria). However, the prepared glaze market is small, so few or no additives are made explicitly for them. However, products like paint, enamel, building and agricultural products, and even cosmetics, are water suspensions and many proven biocides are available for them. But it can be difficult to find and choose one. Companies using these would generally send a sample of contaminated glaze for analysis and recommendation of an anti-bacteria or anti-fungal to prevent it. The percentages recommended are typically quoted based on the weight of the slurry (e.g. 0.25% of the slurry).

Getting biocides approved in a country can be a daunting task that only larger multinational companies can navigate, and the difference in regulatory environments means they may have to produce many variations of a product. This means that even if you find a product from DuPont, TroyCorp or Zschimmer that looks great, it may not be approved for use in your country. Thus, it is best to Google chemical distributors in your area to see what anti-microbials they import and distribute. Fortunately, if a biocide is good for aqueous slurries, paints, adhesives or latex, it should be good for glazes (in the proportion they recommend).

Ceramic supply stores for potters and hobby do not generally carry biocides. And issues with spoiled glazes are rare enough, unless of course you live in a hot damp climate, that DIY glaze making potters can live without them by simply avoiding bio-contamination when mixing and using the slurries, and avoiding storing them in overly warm places or in bright light. As a potter or hobbyist, what insurance against microbial could you employ? Simply adding few drops of Detol or bleach in newly mixed glazes might suffice. A possible biocide source is the DIY personal care products industry - they have preservatives graded from “wash off” to “leave in” products, including soaps, shampoos, moisturizers and lip balms. Percentage additions also range from 0.1%.

Is your contaminated glaze hazardous to handle? Likely not - but to be sure would be as difficult to establish as determining what biocide and how much is needed to fix it. The best course is to throw it out. That being said, it might be possible to dry it out to a powder, sterilize the powder and then remix it.

Micro-organisms do not just grow in glazes, over time mold can grow on pugged clay (stored in plastic bags). The amount and type of growth depend on temperature and available light, time and type of clay. The process is expected and natural. It might seem logical that porcelains, being made from higher purity materials and having a denser matrix and lacking larger particles, would grow less mold. But such is not the case. Often, the surface mold grows in small spots of intense color, dark enough that potters can mistake it for iron impurities. Patching patterns of discoloration (a slightly different shade of the clay itself) can penetrate into the clay from the surface. Inside the clay slug itself, aging can amplify the spiral pattern created by the pugmill, even creating zones of stiffer and softer clay, These are all manifestations of the aging process and seldom manifest an odour, it is thought these even improve the plastic properties. A few moments of wedging will typically bring the material back to its pristine production consistency.

Related Information

Mold growing in a clay having added xantham gum

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

This slug is about 6 months old. It contains 0.75% gum. The gum destroys the workability of the clay so it is not useful in this application anyway.

A bucket of glaze smells totally rank! What to do?

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

In some places and climates, this is more of a problem than in others. It is often not something that can just be ignored because the rheology of the slurry will likely be affected. Is there a magic chemical one can dump in to fix it? Not really. The subject of microorganisms in glaze slurries can be as complicated as you want to make it. This is because there are just so many different things that could be causing the stink. And there is no one chemical that treats them all. Even if there was, it's use would be focussed on prevention rather than fixing a problem. And, it would being its own issues, hazards and specific procedures. There are some simple things to know about dealing with microorganisms in glazes that should enable to you keep relatively free of this issue.

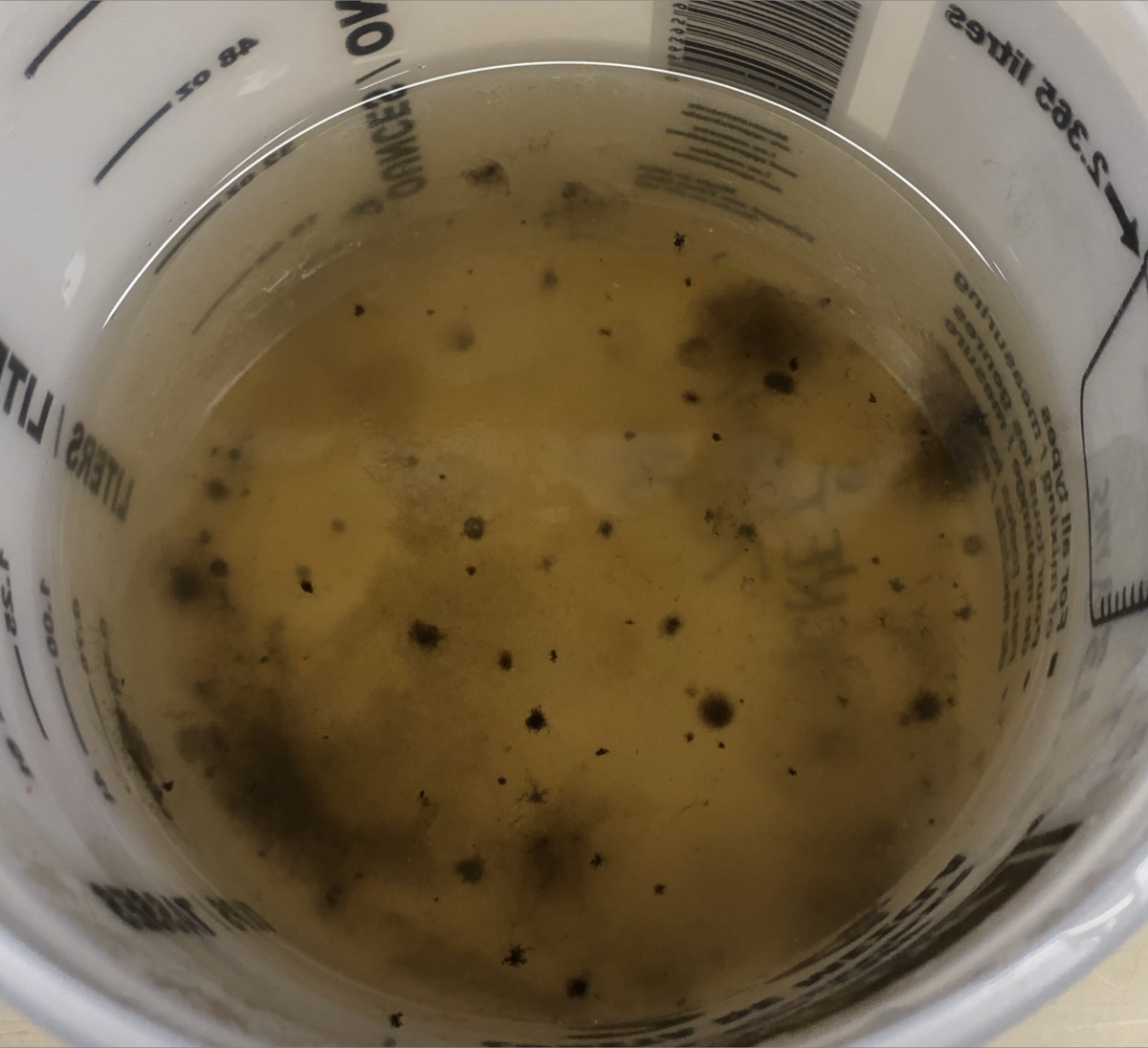

Something gross is growing in this jar of prepared glaze

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Even though most prepared glazes contain some sort of biocide, apparently this can still happen!

Mold (actually sprouting leaves) has grown on pugged clay

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

After 10 months of storage (where there is sunlight).

CMC gum solutions can go bad

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

That is why glazes containing CMC often need a biocide if they are going to be stored for extended periods. We made this one. The gallon jar of Laguna gum solution sitting next to this did not go bad, that means they have added some sort of anti-microbial agent.

Mold has appeared on the surface of an eight-month-old slug of potters clay

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Clay is Plainsman M370. This is part of the aging process and can appear on any clay, depending on the conditions of storage (especially if stored in a very warm place or one exposed to sunlight). On the right this material has been fired to cone 6. The spots, although dark in the wet state, are burned away during firing. Mixing these specks back into the interior of the slug can be done quickly by wedging (diminishing worries about any allergy issues).

Another reason why clay should be wedged or kneaded

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Left: A high-contrast photo of a cut across the cross section of an eight-month-old slug of Plainsman M370 pugged clay. Right: A cut of a just-produced material (which will exhibit the same pattern in eight more months). You can feel different stiffnesses as you drag your finger across this clay, these are a product of the aging process combined with the natural lamination that a pugmill produces. Clearly, the older material needs to be wedged before use in hand building or on the wheel.

Aged commercial clay really needs to be wedged before use

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

This is a cut through an eight-month-old slug of pugged clay. The cut was done near the surface. The patchy coloration is a by-product of the aging process. If a slice of this was fired in a kiln, an even and homogeneous white surface would emerge, with no hint of what you see here. A few moments of wedging will mix the matrix and ready it for wheel throwing or hand forming.

Discoloration as porcelain ages

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

This is a slug of Grolleg porcelain that is about 1 year old. When pugged it was perfect homogeneous white. These streaks and specks have all developed over time as it ages. A slice of this cross section fires pure white.

Commercial glazes gone bad. Can they be used?

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

On the left is an ultra-white, doubtless containing 20% zircon. It smells bad and has settled out, indicating that mocrobials have degraded the gelling agent. The one on the right is bright yellow, it would thus contain significant encapsulated stain. These stains have proven troublesome, they seem to spawn the growth of a different bacteria, it smells much worse. And the slurry has gone rotten, turning black. Companies add biocides during mixing and try to minimize the amount used (since they are based on chloroform). However, the many variables in materials and procedures will mean that some glazes can slip through the system and go bad even if unopened. And, users can introduce microbials during use. Of course, biocides have shelf lives, thus products employing them also do. Can these be used (if you can handle the smell): Yes, if they still paint well. Glazes are powdered rock in water, microbes cannot eat rock!

All of this being said, Amaco recommends the addition of a teaspoon of bleach to fix many cases of this, so try that first. Of course, if the gum has degraded it will have to be added (1% of dry weight in jar blender mixed).

Inbound Photo Links

Control gel using Veegum, brushing properties with CMC gum |

Links

| Typecodes |

Biocide

These are added to glazes and bodies to prevent the growth of micro organisms. Often targeted at bacteria, mold or fungi. |

| URLs |

https://www.zschimmer-schwarz.com/en/ceramic-auxiliaries/tiles/glaze-additives/biocides

Zschimmer & Schwarz Biocides |

| URLs |

https://www.microban.com/antimicrobial-solutions/applications/antimicrobial-ceramics

Microban.com Antimicrobials for Ceramics |

| URLs |

http://microbialcontrol.dupont.com

DuPont Microbial Control Website |

| URLs |

https://lanxess.com

Lanxess Home Page |

| URLs |

http://www.troycorp.com

Troy Corp Website |

| URLs |

https://www.eastman.com

Eastman Chemical Website |

| URLs |

Antimicrobial properties of copper on Wikipedia A tiny amount of copper carbonate (e.g. a few grams in a 5 gallon bucket) are said to be anti-microbial. Even a piece of copper wire. |

| URLs |

https://aussiesoapsupplies.com.au/ingredients-and-raw-materials/preservatives-and-antioxidants/

Examples of preservatives used in DIY soap production |

| Hazards |

Fighting Micro-Organisms in Ceramics

An inventory of all the kinds of microbes that can grown in aqueous products and how to prevent their appearance and deal with them after they appear. |

| Hazards |

Clay Toxicity

Is clay toxic? No. Should you breathe it? No. |

| By Tony Hansen Follow me on        |  |

Got a Question?

Buy me a coffee and we can talk

https://digitalfire.com, All Rights Reserved

Privacy Policy