| Monthly Tech-Tip | No tracking! No ads! |

Ceramic Binder

Binders are glues that harden ceramic powders as they dry. They enable improved surface adherence. And slower drying.

Key phrases linking here: ceramic binder - Learn more

Details

A classic ceramic glaze (a water based slurry of feldspar, clay and silica powders) can can be applied to the surface of porous ceramic bisque (or even leather hard or dry ware) and it will dry durable enough to be able to handle the ware for further processing. However, in many applications (e.g. where the powder contains little plastic clay or high dry durability or surface adherence are needed), an organic binder must be employed. Binders are examples of glaze additives.

Binders are basically glue, they are designed to harden and strengthen bodies and glazes as they dry. Ceramic powders containing binders can exhibit remarkable surface adherence and durability on drying. Binders are especially important in glazes, bonding them to even dense bisque surfaces. Binders in enamels can even bond them to metal. The mechanism of a binder can be as simple as a glue that hardens and adheres particles to each other (and any surface they touch). Body binders make it possible to form powders that would not otherwise hold a shape (e.g. dust pressing is a common method for these). In fact, bodies having zero clay content (e.g. dental porcelain) can still be hardened using a binder. Glaze binders make it possible to use slurries with very low plastic clay content (either no clay or highly processed clay materials that have little binding power). Conversely, binders can be so effective that a high-clay engobe or slip that would normally shrink, crack and fall off can be multi-layered on the same bisque surface (by the addition of CMC gum).

Binders come at a cost. They can be very expensive. They slow down drying. They make slurries messy and difficult to process and handle. Cleanup is much more difficult. They generate CO2 as they decompose during firing. In some industries, like tile, binders are avoided where possible, or carefully chosen and monitored (e.g. sodium silicate is used as a binder). As noted, binders are needed to adhere glazes to dense non-porous surfaces (e.g. already-vitrified bone china ware, metal).

Orton cones are a good example of the use of a binder. Cones are made from ceramic materials, yet resist re-wetting when immersed in water. Once they do slake, the slurry is very sticky and very slow to dewater on a plaster bat. Another common example are prepared commercial hobby and pottery glazes. The binder dramatically slows drying, but they have very good brushing properties. It also enables them to adhere to even already-fired glazes or non-porous surfaces. And the dried surface is hard and difficult to remove, even with water.

The world of binders is typically outside the scope of what a typical potter needs to know. Potters are able to use blends of natural materials and minerals (using age old processes) and they adapt their methods to the idiosyncrasies these materials present. Industry, on the other hand, needs to optimize processes, so binders are much more applicable.

If a material name or description includes the word “gum”, that does not mean it is a binder in the above explained sense. Veegum, for example, is a clay. CMC gum is a glue.

Depending on time, temperature, pH, binder can be attacked by microbes or molds. If this happens store in a cooler place, make smaller batches, adjust the pH to make a less friendly environment, or add a biocide (i.e. Tektamer, NaN3). The shelf-life of commercial brushing glazes can be affected for this reason.

Related Information

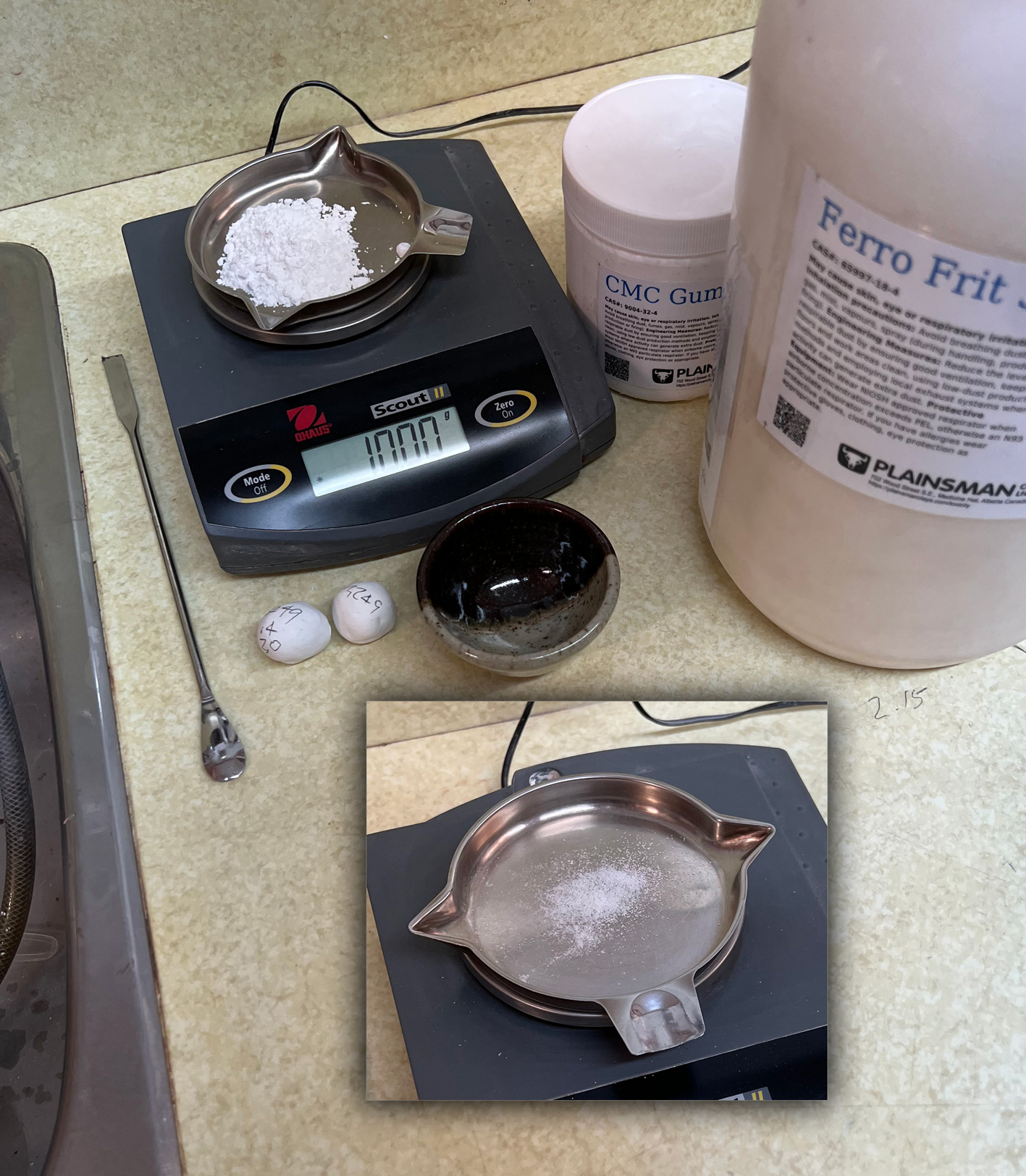

Preparing balls for a melt fluidity test using CMC gum

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

We use 11g of the material being tested, e.g. a frit, (the right amount for one ball), 0.11g CMC (1%). Of course, you need a 0.01g scale to be able to accurately weigh 0.1g (that is a really small amount). Put them in a small ziplock bag, zip it to entrap air and roll the zipper down to inflate it. Shake well to mix. Stir the powder into water (~5-8g) in a small bowl. Pour it onto a plaster slab - it dewaters very quickly (e.g. as little as 10 seconds) - just as the water sheen is gone, peel it up with a rubber rib. Smear it back down and peel it up every few seconds until it is plastic and formable (but not sticky). For better formability use 1.5% CMC gum - however, the ball will dry slower - drying time is an issue with this method, you will need a heat lamp or other drier of some sort (e.g. a dehydrator). You will also need a plaster surface to absorb the excess water (which invariably happens).

Links

| Articles |

Binders for Ceramic Bodies

An overview of the major types of organic and inorganic binders used in various different ceramic industries. |

| Glossary |

Green Strength

The green strength of clay bodies is an important property, it makes them resistant to breakage or damage during handling in production. |

| Typecodes |

Additives for Ceramic Glazes

Materials that are added to glazes to impart physical working properties and usually burn away during firing. In industry all glazes, inks and engobes have additives, they are considered essential to control of cohesion, adhesion, suspension, dry hardness, surface leveling, rheology, speed-of-drying, etc. Among potters, it is common for glazes to have zero additives. |

| Typecodes |

Additives for Ceramic Bodies

Materials that are added to bodies to impart physical working properties and usually burn away during firing. Binders enable bodies with very low or zero clay content to have plasticity and dry hardness, they can give powders flow properties during pressing and impart rheological properties to clay slurries. Among potters however, it is common for bodies to have zero additives. |

| By Tony Hansen Follow me on        |  |

Got a Question?

Buy me a coffee and we can talk

https://digitalfire.com, All Rights Reserved

Privacy Policy