| Monthly Tech-Tip | No tracking! No ads! |

Slip Casting

A method of forming ceramics. A deflocculated (low water content) slurry is poured into absorbent plaster molds. As it sits in the mold, usually 10+ minutes, a layer builds against the mold walls. When thick enough the mold is drained.

Key phrases linking here: slip casting, slip-casting, slip-casts, slip cast, slip-cast - Learn more

Details

Slip casting is the forming of ceramics by pouring or pumping deflocculated (water-reduced) clay slurry, called casting slip, into plaster molds. In the process, the absorbent plaster pulls water from the slurry, and over a period (e.g. 20 minutes) a layer builds up against the mold surface. The slurry is then poured out and, as the item stiffens it shrinks slightly and pulls itself away from the mold enabling removal. This casting process is flexible, capable of producing fine delicate porcelain items yet heavy sanitaryware (they can cast pieces up to 50kg). Slip casting is typically the only option where complex-shaped pieces are needed.

The casting process has some compelling advantages over plastic or dust-forming methods. Consider:

- Many shapes are very difficult or impossible to produce any other way.

- Slip-cast ware can dry-shrink as little as 1.5% (compared to 6%-8% for plastic stoneware bodies).

- Porcelain can be made whiter and more translucent because the dirtier plastic materials are not needed.

- All clay can be reclaimed and put into slip for reuse.

- Slip is easy to magnetically purify and sieve, and its consistency can be adjusted easily for optimum workability.

- Slip-cast ware can be made much lighter and thinner walled.

- With some bodies handles and add-ons can even be applied to dry ware using slip and yet no cracking occurs!

- With control of your clay body recipe it is feasible to adjust it to get higher or lower thermal expansion, greater translucency, or to make a custom body for refractory or low-fire applications.

- The workflow consists of a series of small tasks often separated by period of time. This is such that a potter can integrate slip casting into his existing production to increase output.

- Slip casting can often be done by non-skilled people.

The sanitary ware industry produces the largest tonnage of products using this process. Water closets and sinks are made by casting porcelain and whiteware in complex many-part molds. Traditional plaster molds are heavy, cast sections are thick, and take considerable time to release and extract from the molds (e.g. 8-10 hours). However modern methods employ resin molds, automated mold-handling and filling equipment, pressurization of the slip feed, heated slurry, air-assisted drying, vacuum dewatering of molds, etc to reduce casting cycle time to as little as 20 minutes!

Many types of powdered ceramic can be made into a slurry and cast (except for clays that are high in soluble sulphates or gel on attempts to deflocculate). If the slurry can be suspended and deflocculated, it shrinks enough on drying and has enough strength to hold itself together as it pulls away from the mold, it can be usually cast. Even non-plastics like calcined alumina and silicon carbide can be cast by incorporating small additions of plasticizers and binders. Since the whitest burning clays have low plasticity, casting lends itself to producing white-burning ware.

In industry, casting rate is important. Items need to cast and be extracted from molds quickly (shrink away and hold together). Molds need to be dewatered rapidly. Aside from the above-mentioned automation, much can be done to fine-tune the balance of permeability and plastic strength of a body. It is important to understand the role of each material in the body recipe. Compared to a plastic body a typical industrial casting body has more kaolin, less ball clay, and usually no bentonite. Ball clays and kaolins of the largest ultimate particle size are preferred (since these are more permeable to water passage). The above being said, bodies can actually cast and release too fast, causing issues in production.

Casting bodies that are relatively non-plastic can have very low drying shrinkages compared to plastic ones, ware can be dried quickly with little likelihood of cracking. Separately cast, leather-hard sections can even be glued together with slip and the pieces can be dried without issue. However, as noted, non-plastic ware is often difficult to release from molds - especially if walls are thin or shapes are complex. And it crumbles when cut, even with sharp tools. Some potters thus use a dual-purpose body recipe (e.g. the casting version having 1% bentonite and the plastic version having 3-4% bentonite). The extra leather hard strength and trimability are considered well worthwhile despite much longer casting times. Adding a little plastic clay to a kaolin-only porcelain body is said to add “stress-relief plasticity”, not only reducing the brittleness but also reducing drying cracks.

The casting process does not lend itself to grogged bodies. The grog will not normally suspend well in the slurry. And it adversely affects the rheology of the slip. And it would also be abrasive on mixing and slip-handling equipment.

A common issue with production casting is the recycling of scrap. Typically batch recipes call for a percentage in keeping with how much is generated by the production process. Scrap is commonly less plastic than a virgin mix. The exact reason is less researched than just responding to it as appropriate. One explanation is that the super fine plastic particles get preferentially pulled out of the slurry during time in the molds. The addition of a small amount of bentonite, e.g. 0.5-1%, is the simplest solution.

3D printing technology has many applications to casting, especially for mold-making and tooling (see linked projects below for examples).

Related Information

Delflocculation accomplishes the seemingly impossible

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

It is possible to get that 3000g of porcelain powder into this 1100g of water! And the fluid slurry produced, 2250cc, will fit into the front container. How is this even possible? The water has 11 grams of Darvan 7 deflocculant in it, it causes the clay particles to electrolytically repel each other! An awareness of “this magic” can help give you the determination to master deflocculation, the key enabler of the slip casting process. Determination? Yes, the process is fragile, you must develop the ability to “discover” the right amount of Darvan for your clay mix and water supply. And the ability to recognize what is wrong with a slurry that is not working (too much or little water, too much or little deflocculant).

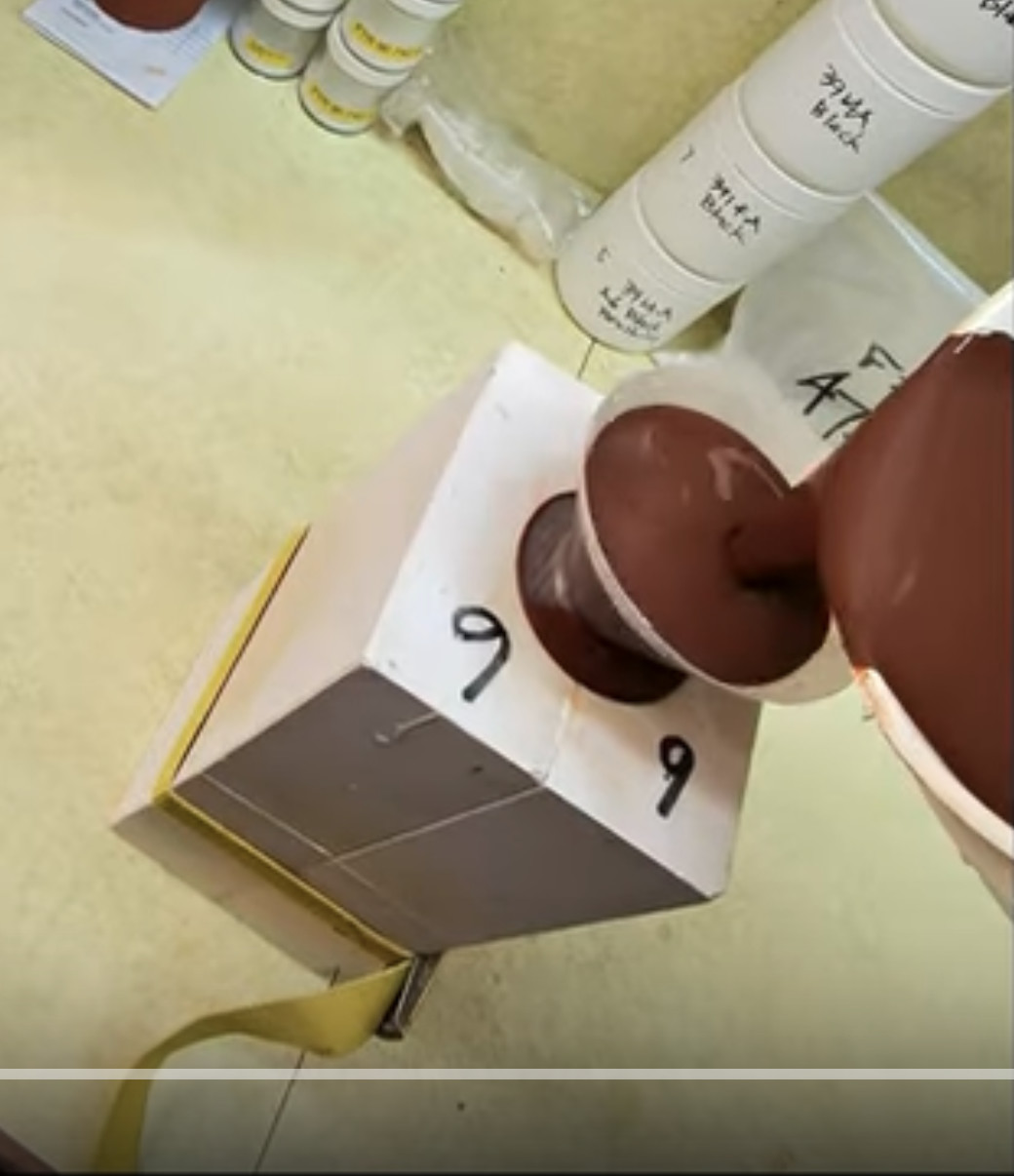

This is how much casting slip 10,000 grams of powder makes

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

There are 8.8 liters of slip in this 2 imperial gallon bucket. The cone 10 stoneware slurry was propeller mixed in a larger bucket. First I stirred about 3/4 of the projected 44g of Darvan into 4000g of water. Then I dumped in 10,000g of the powder (shaken in a plastic bag) and let it sit to slake as much as possible. Then I used a high-energy propeller mixer, and to finish, trickling in extra Darvan until the rheology was right. The slip itself thus weighs 14 kg (31 lb) and has a specific gravity of ~1.75. It has sat overnight and formed a film on the top, but has not settled (indicating that it likely is not over deflocculated). The casting process enables even a hobbyist to make his own custom recipes and tune them over time. Would you like to develop a recipe? An account at Insight-live.com is the first step, that’s where you’ll keep all the development notes, pictures and data.

Here is how vigorously a deflocculated ceramic slurry should be mixed

A video of the kind of agitation needed from a propeller mixer to get the best properties out of a deflocculated slurry. This is Plainsman Polar Ice mixing in a 5-gallon pail. Although it is quite plastic compared to industrial casting slips, it has a specific gravity of 1.76, is very fluid and casts well in the hands of a potter. These properties are a product of, not just the recipe, but the mixer and its ability to put high energy into the slurry.

A slip cast bowl just removed from its plaster mold

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

With a simple open shape like this a thin wall (2-3mm) bowl can be cast in minutes and removed from the mold in minutes more. No other method can produce such thin and even ware with this kind of ease.

More problems measuring glaze specific gravity using a hydrometer

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Potters sometimes call this a "floating thingy". Maybe, because of the problems it presents, it does not make a big enough impression to remember the name! Because of the length of the hydrometer the only container we have is this graduated cylinder. I have to fill it just the right level so it reads near the top. OK, fine. But the hydrometer needs to bob up and down to find home. However, this glaze has our desired thixotropy, which prevents free movement. OK, I will carefully help it find home by pushing it down a little. But then it doesn’t want to bob back up! Ok, I’ll pull it up ... then is doesn't want to go back down to where it should float. Not great. Next problem: The glaze is opaque, I can’t see the reading. Yikes! A better way would be to throw out the hydrometer and just tare the empty cylinder on a scale, fill it to 100 and read the SG as the weight/100. Or fill it to any mark and divide the weight by that.

When to use a hydrometer and when not to

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

If a glaze has already been mixed and gelled to give it thixotropy these things won't bob up and down to home in on the right level. If the glaze is watery enough there are other issues. The one on the right has a 1.0-1.7 scale. Since most pottery glazes need to be 1.4-1.5 specific gravity (40-50 on this scale) it is difficult to get a very accurate reading. And it is long, you will need a container tall enough to float it and enough glaze to fill it. The small hydrometer appears better, it has a scale of 1.2 to 1.45. But it really bobs up and down (so it is even more important that the slurry be runny and thin to give it the freedom to do so). But glaze slurries are creamy. So it is better to weigh a measured volume of glaze slurry and calculate the SG instead. The easiest is a 100cc graduated cylinder (from Amazon.com), if 100 ccs weighs 140 grams, that is 1.4 specific gravity. You don't even have to pour in 100cc, just pour in any amount and divide the weight by the amount.

Confirming slip viscosity using a paint-measuring device

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

A Ford Cup is being using to measure the viscosity of a casting slip. These are available at paint supply stores. This is a #4 (4.25mm opening), it holds 100ml and drains water in 10 seconds. This casting slip has a specific gravity of 1.79. Having made it many times, our experience indicates 40-seconds as a drain target (after high energy mixing). In production situations, the seconds-value this test produces enables an audit-trail for quality control and problem solving. When first mixing a slurry, under-deflocculating and eye-balling the viscosity is typical, during that period the slurry gels while draining and Ford cup measurements are not valid. When the mixing process has been perfected and viscosity stabilized the Ford Cup becomes practical.

Don’t overthink this type of measurement or the type of cup or opening size (you can even make your own cup). You must still determine the optimal flow rate based on experience with your process. This technique is more about maintaining to ongoing adherence to a standard you define.

Talc:Ball Clay bodies have incredible casting properties

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

This bowl is 13cm across yet has a wall thickness of less than 2mm and weighs only 101g! It released from the mold with no problems and dried perfectly round. But it has a key advantage over stonewares and porcelains: When this is fired at cone 04-06 it will stay round!

New Zealand kaolin based slip casts at 1mm thickness. How?

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

This is Polar Ice casting, a New Zealand Halloysite based cone 6 translucent porcelain. The base body recipe would never have enough plastic strength to pull itself from this mold without tearing. But the addition of 1% Veegum gives it amazing strength. This dried cast bowl measures 130mm in diameter and 85mm deep, it only weighs 89 gm! The slip was in the mold for only 1 minute before pour-out. Of course, there is a price to pay for adding the Veegum: Increased casting time and more difficult deflocculation. Regular bentonite can be used in most bodies, but for super-whites like this, Veegum (or equivalent) is the choice. Testing is needed to determine what percentage gives the needed strength yet does not increase the casting time too much. The polar ice information page at plainsmanclays.com has very good information, under the heading “Casting Recipe”, about the challenges and trade-offs of using this kaolin in casting bodies.

Bottle calibration mold demos novel casting methods

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Three slip casting methods are examples of the flexibility potters have compared to manufacturers (especially for small molds like this).

1) 3D-printed locks are stuck on to hold the mold halves together. The casting slip itself adheres them. Dipping the flat surfaces and attaching them takes seconds. This method enables aligning halves accurately and then locking them into place.

2) The 3D-printed pouring spout is also attached using the slip (it also helps hold the mold halves together) and acts as a reservoir and pour-out indicator. Thus, this mold needs no spare.

3) There are no natches (the halves were poured into disposable 3D printed PLA masters - and mate perfectly and align easily).

These three factors simplify the mold design, reduce mold size, improve the fit of parts and simplify pouring, demolding and cleanup for this specific type of piece.

Here is what happens when I underestimate slip pressure

Typical casting slip has a specific gravity of 1.8, that means it is a lot heavier than water. The deeper a mold the more outward pressure the slurry will exert. There is thus good reason to be certain that the mold halves are securely held together. If not, this will happen!

Over-deflocculated ceramic slurry forms a skin

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

In this instance, the slurry forms a skin a few minutes after the mixer has stopped. Casting recipes do not travel well. Over-deflocculation is a danger when simply using the percentage of water and deflocculant shown. Variables in water electrolytes, solubles in materials, mixing equipment and procedures, temperature and production requirements (and other factors) necessitate adapting recipes of others to your circumstances. Add less than the recommended deflocculant to try and reach the specific gravity you want. If the slurry is too viscous (after vigorous mixing), then add more deflocculant. At times, more than what is recommended in your recipe will be needed. After all of this you will be in a position to lock-down a recipe for your production. However flexibility is still needed (for changing materials, water, seasons, etc).

Over deflocculated vs. under deflocculated ceramic slurry

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

The slip on the right has way too much Darvan deflocculant. Because the new recipe substitutes a large-particle kaolin for the original fine-particled material, it only requires about half the amount of Darvan. Underestimating that fact, I put in three-quarters of the amount. The over-deflocculated slurry cast too thin, is not releasing from the mold (therefore cracking) and the surface is dusty and grainy even though the clay is still very damp. On my second attempt I under-supplied the Darvan. That slurry gelled, did not drain well at all and it cast too thick. On the third attempt I hit the jackpot! Not only does it have 1.8 specific gravity (SG), but the slurry flowed really well, cast quickly, drained perfectly and the piece released from the mold in five minutes. Interestingly, on a fourth mix I made an error, putting in too much water, getting 1.6SG. The casting behavior was similar to the over-deflocculated slip (even though the Darvan content was much lower). A good casting slip is a combination of a good recipe, the right SG and the correct level of deflocculation.

The casting slip did not drain well when pouring this mug

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

The slurry contained insufficient Davan deflocculant. During casting it gelled excessively in the mold. Even shaking the piece while pouring out the slip was not enough to loosen it up and get a good drain. If slurry rheology is not right the quality of ware produced is affected like this.

Crawling glaze on slip cast ware is common

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

This cone 6 white glaze is crawling on the inside and outside of a thin-walled cast piece. This happened because the thick glaze application took a long time to dry, this extended period, coupled with the ability of the thicker glaze layer to assert its shrinkage, compromised the fragile bond between dried glaze and fairly smooth body. There are several measures that can be taken to solve this problem. The ware could be heated before glazing, the glaze applied thinner, or glazing the inside and outside could be done as separate operations (with a drying period between).

A heavily grogged casting body still casts with a smooth surface!

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

20% 20-40 mesh grog was added to a Pyrax/Kaolin thermal shock body. While the insides of the pieces have a very rough surface, the outsides are smooth! Grogged casting slips have issues with the particle settling during storage and casting, however in this body the grog suspends long enough for a 15 minute casting time (and it easily mixes back in after storage). Pieces can be put into the kiln wet-out-of-the-mold and fast-heated to 250F and they do not crack.

Casting plates, is it practical?

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

No. Because you will face a whole array of problems, not the least of which is the tearing shown here. This is the first, poor mold release, or more correct, impossible mold release! Plates will be too thin-walled. If you cast them longer wall thickness will be uneven. Edges will crack like this (because of poor plasticity). They will warp during drying. They will lack dry strength for handling. They will warp during firing. You won't be able to get a good rim. You won't be able to cast a foot ring without an indent showing on the inside. Note here that another issue is at play: The clay is either not plastic enough to cut cleanly at the rim, without tearing. Or, it is being cut too late or with a dull knife. These tears provide places for cracks to initiate. Plates are much better made using the jiggering, ram pressing or dust pressing processes. Or by throwing them on plaster batts.

Cast handle on thrown mug, pulled handle on cast mug

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Left #1: A thrown mug with a slip-cast handle.

Right #2: A slip-cast mug with a pulled handle.

#1 is much less likely to crack on drying? Why? The much higher drying shrinkage of the plastic throwing clay is the main issue. A cast mug, stiff enough for handling, may have as little as 1% shrinkage left while the pulled handle being attached could have 5% or more. While #1 has survived, stresses lurk within seeking relief (e.g. when bumped). The situation is much more favourable with a cast handle on a thrown mug. At leather hard it may have 3% shrinkage left. A fresh-out-of-the-mold cast handle would have about the same - so they will dry happily together. Of course they also need to have similar firing shrinkages so the kiln does not put the join under stress.

Top influencers are doing slip casting

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Pottery and sculpture is not just about wheel throwing and hand building. Plaster molds can be the forming method of choice for many people and types of objects. Pieces that are difficult to dry, especially large, are perfect opportunities for slip casting (this is now toilets and sinks are made). Shapes that are difficult to hand-build but easy to form in 3D (in apps like Nomad) can be made by 3D printing press molds or case molds (into which plaster is poured). Using CAD tools and 3D printing, it is now possible to do one-off pieces, then make small changes to the design and remake them. Plaster is inexpensive.

Inbound Photo Links

Why mid-fire Grolleg porcelain is ideal for both throwing and casting |

A draining issue with a slip cast bottle It is turning inside out! |

Links

| Glossary |

Rheology

In ceramics, this term refers to the flow and gel properties of a glaze or body suspension (made from water and mineral powders, with possible additives, deflocculants, modifiers). |

| Glossary |

Deflocculation

Deflocculation is the magic behind the ceramic casting process, it enables slurries having impossibly low water contents and ware having amazingly low drying shrinkage |

| Glossary |

Ceramic Slip

The term Slip can have various meanings in traditional ceramics. |

| Glossary |

Water in Ceramics

Water is the most important ceramic material, it is present every body, glaze or engobe and either the enabler or a participant in almost every ceramic process and phenomena. |

| Glossary |

Specific gravity

In ceramics, the specific gravity of slurries tells us their water-to-solids ratio. That ratio is a key indicator of performance and enabler of consistency. |

| Glossary |

Throwing

|

| Glossary |

Sanitary ware

A type of porcelain zircon-glazed ceramic that includes bathtubs, sinks, toilets, etc. |

| Glossary |

Casting Slip

Casting slips are among the easiest clay bodies to make yourself. The ability to make and tune your own will open many doors in your production process. |

| Articles |

Understanding the Deflocculation Process in Slip Casting

Understanding the magic of deflocculation and how to measure specific gravity and viscosity, and how to interpret the results of these tests to adjust the slip, these are the key to controlling a casting process. |

| Materials |

Boron Nitride

|

| URLs |

https://ceramicninja.com/

Technical information about the production of sanitaryware Based in India. And excellent resource to understand materials, casting and molding technologies. |

| URLs |

https://www.lagunaclay.com/materials

Laguna web page with "Plaster/Mold Making Catalog" link |

| URLs |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plaster

Plaster at Wikipedia Information on the chemical reactions that occur when gymsum is heated. |

| URLs |

https://www.instagram.com/hammerlyceramics/

Hammerly Ceramics - Slipcasting of incredible mugs |

| Projects |

2019 Jiggering-Casting Project of Medalta 66 Mug

My project to reproduce a mug made by Medalta Potteries more than 50 years ago. I cast the body and handle, jigger the rim and then attach the handle. 3D printing made this all possible. |

| Projects |

Coffee Mug Slip Casting Mold via 3D Printing

A potter can now use AI, 3D CAD, 3D printing and custom clay bodies to slip-cast beautiful quality stoneware pottery mugs. It is efficient and practical. |

| Projects |

Medalta Ball Pitcher Slip Casting Mold via 3D Printing

A project to make a reproduction of a Medalta Potteries piece that was done during the 1940s. This is the smallest of the three sizes they made. |

Video |

Slip cast a stoneware beer bottle

I will mix the slurry, assemble the mold, attach the 3D-printed pour spot, pour in the slip, pour it out, remove the spout, trim the lip, split the mold, extract the bottle and drill the holes for the swing-top stoppers. |

| By Tony Hansen Follow me on        |  |

Got a Question?

Buy me a coffee and we can talk

https://digitalfire.com, All Rights Reserved

Privacy Policy