| Monthly Tech-Tip | Feb 14-15, 2026 - Major Server Upgrade Done | No tracking! No ads! |

Glaze Bubbles

Suspended micro-bubbles in ceramic glazes affect their transparency and depth. Sometimes they add to to aesthetics. Often not. What causes them and what to do to remove them.

Key phrases linking here: glaze bubbles, bubbling, clouding - Learn more

Details

As glazes melt, gases from the decomposition of organics, carbonates, sulphates and hydrates are generated (if the body was glazed green, or unbisqued, many more of these gases will be present). If glazes are already melting while the gases are being generated, bubbles form and suspend in the glass melt. Ideally, ware should be bisqued fired at the highest possible temperature (yet still be absorbent enough to glaze). If ware is being fired green, kilns should be soaked at the highest point possible before the glaze melts (on the way up).

With increasing temperature, these bubbles will dissipate if the glaze is melting (if the layer is thin enough, the melt is fluid enough or has a low enough surface tension and adequate time is available). For colored and reactive glazes, less attention is necessary because the bubbles often cannot be seen. However, transparents demand that this be considered, since bubbles cloud the glass and make it unsightly, especially for darker colored bodies. Strangely, at lower temperatures it is easier to get a crystal-clear glaze on most bodies.

Industry requires transparent glazes that can be fired quickly yet have good clarity, so considerable emphasis is placed on a bubble-free glass. Fritted glazes generate far fewer bubbles, although they can still come from the clay portion of the recipe (used for suspending the glaze slurry), binders (used for hardening), and from colorants under the glazes. Efforts are made to create a dense laydown to reduce air pockets in the dried glaze layer. Highly processed bodies that use high-quality clays (low carbon) and fine-ground materials also breed a more perfect glass.

Glaze melts are not homogeneous (especially in the early stages of melting) and a beneficial side-effect of the bubbles is their mixing action. This produces a glass of less phase change (and therefore more even refraction).

Bubbles can often be greatly reduced by and drop-and-hold firing schedule.

It might seem that commercial brushing glazes should fire crystal-clear all the time, or at least better than anything you could make on your own. But this is not the case, they suffer the same problem. In their documentation and websites manufacturers often refer to the tendency of their clear glazes to cloud if applied in too many coats (two coats are often recommended).

Related Information

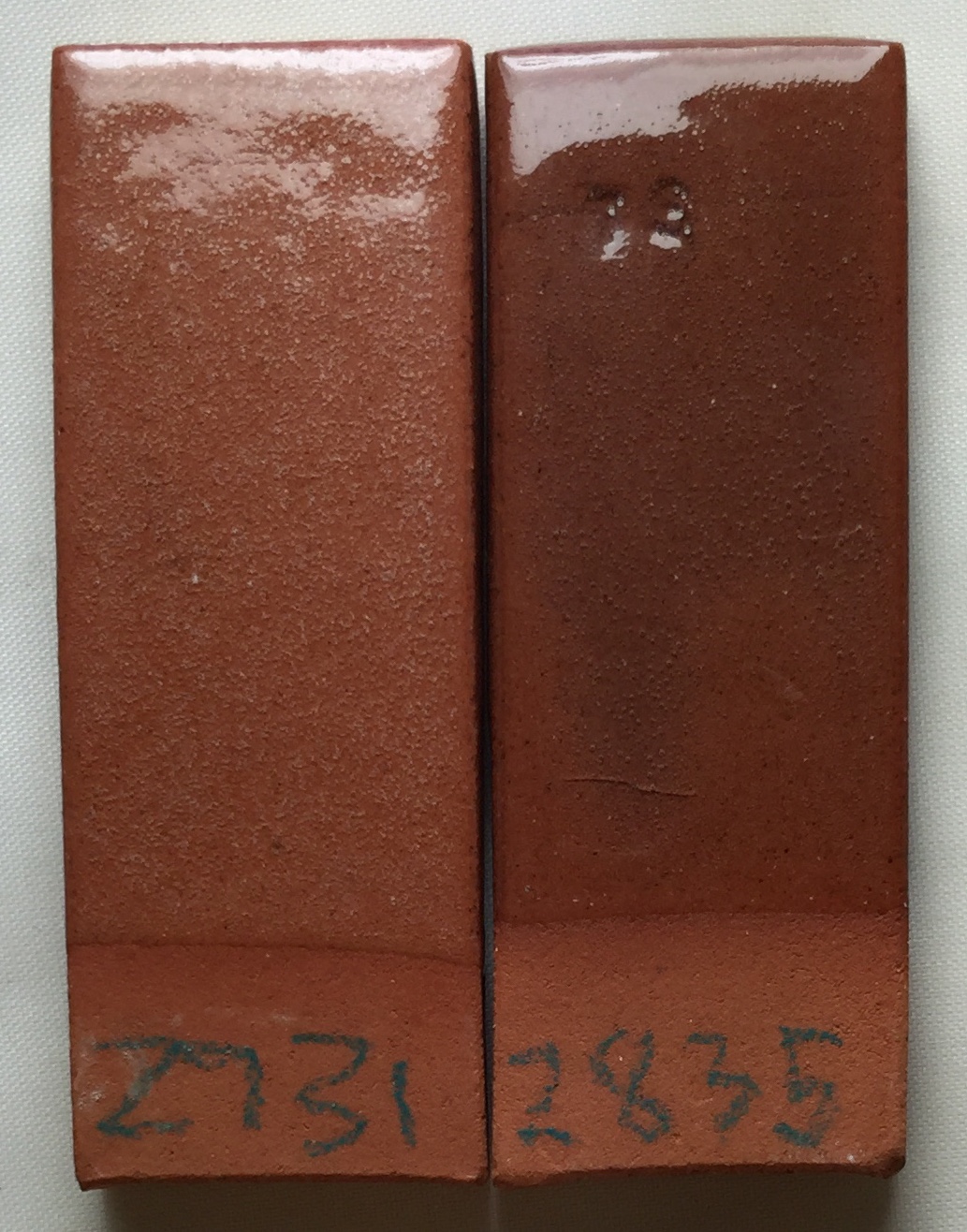

Glaze with an encapsulated stain is bubbling. It needs Zircopax.

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

These two pieces are fired at cone 6. The base transparent glaze is the same - G2926B Plainsman transparent. The amount of encapsulated red stain is the same (11% Mason 6021 Dark Red). But two things are different. Number 1: 2% Zircopax (zircon) has been added to the upper glaze. The stain manufacturers recommend this, saying that it makes for a brighter color. However, that is not what we see here. What we do see is the particles of unmelting zircon acting as seeds and collection points for the bubbles (the larger ones produced are escaping). Number 2: The firing schedule. The top one has been fired to approach cone 6 and 100F/hr, held for five minutes at 2200F (cone 6 as verified in our kiln by cones), dropped quickly to 2100F and held for 30 minutes.

Zircopax as a fining agent to de-bubble a stained glaze

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

The cone 03 porcelain cup on the left has 10% Cerdec encapsulated stain 239416 in the G2931K clear base. The surface is orange-peeled because the glass is full of micro-bubbles that developed during the firing. Notice that the insides of the cups are crystal-clear, no bubbles. So here they are a direct product of the presence of the stain. The glaze on the right has even more stain, 15%. But it also has a 3% addition of Zircopax (zircon). Suppliers of encapsulated stains recommend a zircon addition, but are often unclear about why. Here is the reason: It is a "fining agent".

G2931F Ulexite-based transparent bubbles, G2931K frit-based version does not

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

I melted these two 9 gram GBMF test balls on tiles to compare their melting (the chemistry of these is identical, the recipes are different). The Ulexite in the G2931F (left) drives the LOI to more than 14%. That means the while the ulexite is decomposing during melting it is creating gases that are creating bubbles in the glass. Notice the size of the F is greater (because it is full of bubbles). While this seems like a serious problem, in practice the F fires crystal-clear on most ware.

Bubble city with Seattle Midnight body and G3806C glaze at cone 01, 4 and 5

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

This black body is made by Seattle Pottery Supply. Surfaces like this are obviously not functional, but for decorative ware? Yes! How does this happen? This body contains a material that is adding to its LOI (likely raw or burnt umber). Not just that, but the gases are being expelled at the wrong time. How is that? The glaze is fluid at cone 6 and begins melting way down around cone 04. It is melting long before the gases of decomposition from the body are finished being expelled. So they have to bubble up through the glaze, creating the effect you see here. This body is actually over-mature and brittle at cone 5, but at cone 01 its strength is fairly good.

2% iron oxide in a glossy terra cotta glaze gives better color, less clouding

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Both pieces are the same clay body, Plansman L215. Both are fired to cone 03. Both are glazed using G1916Q borosilicate recipe. The glaze on the piece on the left has 2% added iron oxide (sieved to 80 mesh). Each particle or agglomerate of iron (which is refractory in this situation) acts to congregate the micro-bubbles so they can better exit the glaze layer. Notice also how much richer the color is as a result. The piece on the right, without the added iron oxide, is neither as red nor as transparent. Of course, I had to be careful not to apply the glaze too thickly on both.

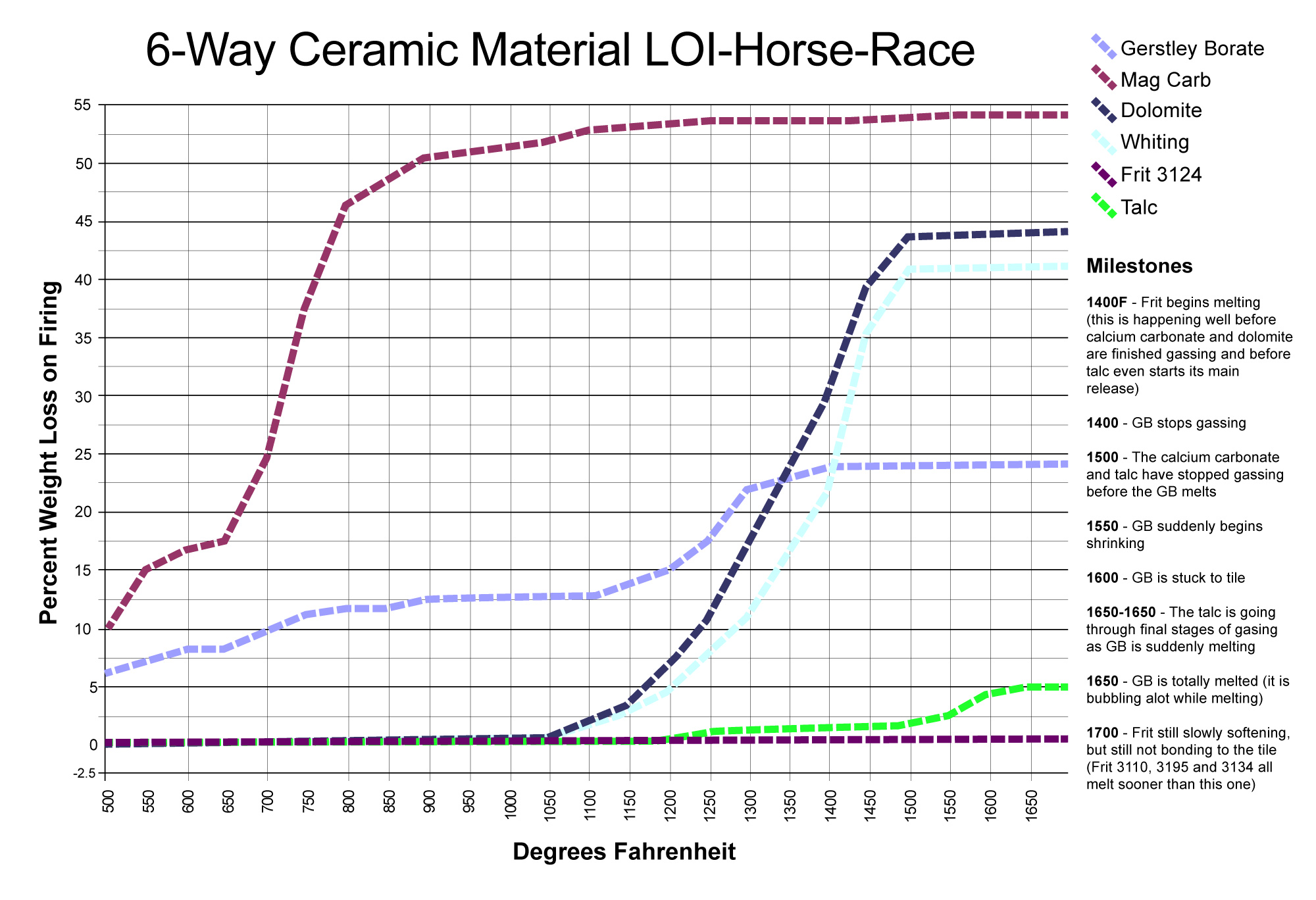

LOI horse race with surprising winners

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

This chart compares the decompositional off-gassing (% weight Loss on Ignition) behavior of six glaze materials as they are heated through the range 500-1700F. It is amazing how much weight some can lose on firing - for example, 100 grams of calcium carbonate generates 45 grams of CO2! This chart is a reminder that some late gassers overlap early melters. That is a problem. The LOI of these materials can affect glazes (causing bubbles, blisters, pinholes, crawling). Talc is an example: It is not finished gassing until 1650F, yet many fritted glazes have already begun melting by then. Even Gerstley Borate, a raw material, begins to melt while talc is barely finished gassing. Dolomite and calcium carbonate Other materials also create gases as they decompose during glaze melting (e.g. clays, carbonates, dioxides).

Close-up of cone 10R celadon bubbles suspended in the glass

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

This is happening because this glaze lacks flux and is not fluid enough to enable their migration. In the upper half they are more evident (double thickness).

Calcium carbonate and glaze bubbles

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

The two cone 04 glazes on the right have the same chemistry but the center one sources it's CaO from 12% calcium carbonate and ulexite (the other from Gerstley Borate). The glaze on the far left? It is almost bubble free yet it has 27% calcium carbonate. Why? It is fired to cone 6. At lower temperatures carbonates and hydrates (in body and glaze) are more likely to form gas bubbles because that is where they are decomposing (into the oxides that stay around and build the glass and the ones that are escaping as a gas). By cone 6 the bubbles have had lots of time to clear.

A body containing manganese bubbles the glaze

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Laguna Barnard Slip substitute fired at cone 03 with a Ferro Frit 3195 clear glaze. The very high bubble content is likely because they are adding manganese dioxide to match the MnO in the chemistry of Barnard (it gases alot during firing).

Micro bubbles in low fire glaze. Why?

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Left: G1916Q transparent fired at cone 03 over a black engobe (L3685T plus stain) and a kaolin-based low fire stoneware (L3685T). The micro-bubbles are proliferating when the glaze is too thick. Right: A commercial low fire transparent (two coats lower and 3 coats upper). A crystal clear glaze result is needed and it appears that the body is generating gases that cause this problem. Likely the kaolin is the guilty material, the recipe contains almost 50%. Kaolin has a 12% LOI. To cut this LOI it will be necessary to replace some or all of the kaolin with a low carbon ball clay. This will mean a loss in whiteness. Another solution would be diluting the kaolin with feldspar and adding more bentonite to make up for lost plasticity.

Glaze bubbles on buff and red burning bodies at cone 6

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

These Plainsman Midstone and Redstone cups are fired to cone 6 with M340 Transparent glaze liner (these are raw materials that body manufacturers incorporate into their products in fairly high percentages). Notice how many more glaze bubbles there are with the red cup. This is typical using other transparent glazes also. To get a bubble-free clear on this red burning body a glaze having a higher melt fluidity is needed.

Why is this transparent so full of bubbles?

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

An example of how a micro-bubble population in the matrix of a transparent glaze can partially opacify it. If this glaze was completely transparent, the red clay body would show much better. However this is not the fault of the glaze. On a white body it would be more transparent. The problem is the terra cotta body. This is fired at cone 02. As the body approaches vitrification the decomposition of particles within it generate gases that bubble up in to the glaze. A positive aspect of this phenomena that this glaze could be opacified using a lower percentage of zircon.

This type of glaze responds better to opacifier additions.

Is clear glazing a dark burning oxidation stoneware a good idea? Likely not.

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Dark bodies tend to have more carbon impurities and the burnout of these can generate gases that create bubbles in the glaze. Because of the dark background, the bubbles impart a muddy look. The body on the left is a finer particle size, so the lower thinner glazed section is a partial success, but the upper section is bubbling. The body on the right, although a more pleasant red color, is bubbling worse. Notice also that the warm color of the body is at least largely lost under the glaze. At its worst pinholes can appear.

Perfect storm to create massive bubbling in a low fire kiln

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

The clay is terra cotta. It is volatile between 04 and 02, becoming dramatically more dense and darker colored. The electronic controller was set for cone 03, but it has fired flat (right-most cone), that means the kiln went to 02 or higher. At 02 the body has around 1% porosity, pushing into the range where the terra cotta begins to decompose (which means lots of gas expulsion). The outsides of some pieces blistered badly while the insides were perfect (because they got the extra radiant heat). The firing was slow, seven hours. Too long, better to make sure ware is dry and fire fast. Another problem: The potter was in a rush and the pieces were not dry. These factors taken together spelled disaster.

Example of how bubbles dissipate in a glaze with increasing temperature

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

This is a Gerstley Borate based recipe (45%) melted in crucibles at increasing temperatures. Although the recipe is well melted at cone 2, it is still not fluid enough to enable their migration in the time available. By contrast, the melt at the upper temperature is much less viscous, enabling all bubbles to completely clear on the thinner sections. If this glaze were applied to ware it would be in a thin layer and the bubbles would likely clear at cone 6. Not to be ignored is the degree to which the thousands of bubbles passing upward through the melt have helped to mix the melt and remove discontinuities in the cone 7 and 8 specimens.

What material makes the tiny bubbles? The big bubbles?

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

These are two 10 gram GBMF test balls of Worthington Clear glaze fired at cone 03 on terra cotta tiles (55 Gerstley Borate, 30 kaolin, 20 silica). On the left it contains raw kaolin, on the right calcined kaolin. The clouds of finer bubbles (on the left) are gone from the glaze on the right. That means the kaolin is generating them and the Gerstley Borate the larger bubbles. These are a bane of the terra cotta process. One secret of getting more transparent glazes is to fire to temperature and soak only long enough to even out the temperature, then drop 100F and soak there (I hold it half an hour).

Glaze bubbles behaving badly!

We see it in a melt fluidity test.

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

These melted-down-ten-gram GBMF test balls of glaze demonstrate the different ways in which tiny bubbles disrupt transparent glazes. These bubbles are generated during firing as particles in the body and glaze decompose. This test is a good way to compare bubble sizes and populations, they are a product of melt viscosity and surface tension. The glaze on the top left is the clearest but has the largest bubbles, these are the type that are most likely to leave surface defects (you can see dimples). At the same time its lack of micro-bubbles will make it the most transparent in thinner layers. The one on the bottom right has so many tiny bubbles that it has turned white. Even though it is not flowing as much it will have less surface defects. The one on the top right has both large bubbles and tinier ones but no clouds of micro-bubbles.

Cone 6 glazes can seal the surface surprisingly early - melt flow balls reveal it

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

These are 10 gram balls of four different common cone 6 clear glazes fired to 1800F (bisque temperature). How dense are they? I measured the porosity (by weighing, soaking, weighing again): G2934 cone 6 matte - 21%. G2926B cone 6 glossy - 0%. G2916F cone 6 glossy - 8%. G1215U cone 6 low expansion glossy - 2%. The implications: G2926B is already sealing the surface at 1800F. If the gases of decomposing organics in the body have not been fully expelled, how are they going to get through it? Pressure will build and as soon as the glaze is fluid enough, they will enter it en masse. Or, they will concentrate at discontinuities and defects in the surface and create pinholes and blisters. Clearly, ware needs to be bisque fired higher than 1800F.

Frits melt so much more evenly and trouble free

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

These two specimens are the same terra cotta clay fired at the same temperature (cone 03) in the same kiln. The chemistry of the glazes is similar but the materials that supply that chemistry are different. The one on the left mixes 30% frit with five other materials, the one on the right mixes 90%+ frit with one other material. Ulexite is the main source of boron (the melter) in #1, it decomposes during firing expelling 30% of its weight as gases (mostly CO2). These create the bubbles. Each of its six materials has its own melting characteristics. While they interact during melting they do not mix to create a homogeneous glass, it contains phases (discontinuities) that mar the fired surface. In the fritted glaze all the particles soften and melt in unison and produce no gas. Notice that it has also interacted with the body, fluxing and darkening it and forming a better interface. And it has passed (and healed) most of the bubbles from the body.

Underglazes require a fluid melt transparent

But extra melt fluidity comes at a cost

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

These porcelain mugs were decorated with the same Amaco Velvet underglazes (applied at leather hard), then bisque fired, dipped in clear glaze and fired to cone 6 (using a drop-and-hold schedule). While the G2926B clear glaze (left) is normally a great glossy transparent for general use, its melt fluidity is not enough to clear the micro-bubble clouds that dull the colors below (while these bubbles are a product of the LOI of body and glaze, underglaze colors can really generate them too). However, the G3806C recipe (right) has a more fluid melt that better enables bubble escape. But such glazes have downsides. The melt fluidity requires care not to get it too thick (or it will run). Its high flux content means it is not as durable. And, its high KNaO content raises the thermal expansion (COE) considerably (and thus the danger of crazing). This porcelain has a high enough COE to fit this, but this glaze crazes on others (that's why I always use the G2926B on the insides of ware). To get even better transparency a thinner layer could be applied (by mixing it as a brushing glaze).

High LOI materials can turn your glaze into Aero chocolate!

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

The smooth surface of this blistering glaze has been ground off to reveal how serious the bubble problem really is. If the body or glaze itself is generating gases of decomposition at the wrong time, and the glaze has too little melt fluidity to pass the bubbles, this can happen. Opacifiers (especially zircon) and stains can reduce melt fluidity dramatically. Even glossy smooth glazes can have bubbles lurking just below the surface, wear and tear on a piece can open them up, creating micro holes that roughen the surface.

Has a cone 5 bisque released Pandora particles?

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

An art tile company is bisque firing a heavily grogged red stoneware body to cone 5 and then finishing with a range of low temperature boron glazes. But these glaze bubble and blister defects are happening! There appears to be some sort of LOI gas-monster particles present. They could be in the grog. And, the body contains two dark burning fireclays, both could contain also rogue particles. To identify them a sieve could be used to pull out the larger ones (e.g. 35 or 42 mesh) and these could be spread in a thin layer onto a porcelain tile and fired to cone 5. Taking closeup photos before and after should spot the guilty ones, they will have a visibly different form (e.g. melting, puffing up, altered color). These pandora particles seem to be activated at cone 5 and capable of continuing to gas even at low refire.

Underglazes at low fire are brighter than at medium temperature

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Medium temperature transparents do not shed micro bubbles as well, clouds of these can dull the underlying colors. Cone 6 transparents must be applied thicker. The stains used to make the underglazes may be incompatible with the chemistry of the clear glaze (less likely at low fire, reactions are less active and firings are much faster so there is less time for hostile chemistry to affect the color). However underglazes can be made to work well at higher temperatures with more fluid melt transparents and soak-and-rise or drop-and-soak firing schedules.

What does it take to get a crystal-clear low fire transparent? A lot!

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

These three cups are glazed with G1916S at cone 03. The glaze is the most crystal clear achieved so far because it contains almost no gas producing materials (not even raw kaolin). It contains Ferro frits 3195 and 3110 plus 11 calcined kaolin and 3 VeeGum. Left is a low fire stoneware (L3685T), center is Plainsman L212 and right a vitreous terra cotta (L3724F). It is almost crystal clear, it has few bubbles compared to the kaolin-suspended version. These all survived a 300F/icewater IWCT test without crazing!

An ultra-clear brilliantly-glossy cone 6 clear base glaze? Yes!

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

I am comparing 6 well known cone 6 fluid melt base glazes and have found some surprising things. The top row are 10 gram GBMF test balls of each melted down onto a tile to demonstrate melt fluidity and bubble populations. Second, third, fourth rows show them on porcelain, buff, brown stonewares. The first column is a typical cone 6 boron-fluxed clear. The others add strontium, lithium and zinc or super-size the boron. They have more glassy smooth surfaces, less bubbles and would should give brilliant colors and reactive visual effects. The cost? They settle, crack, dust, gel, run during firing, craze or risk leaching. Out of this work came the G3806E and G3806F.

Glaze melt fluidity comparison between G2931F and fritted G2931K show the effect of LOI

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

These two glazes have the same chemistry but different recipes. The F gets its boron from Ulexite, and Ulexite has a high LOI (it generates gases during firing, notice that these gases have affected the downward flow during melting). The frit-based version on the right flows cleanly and contains almost no bubbles. At high and medium temperatures potters seldom have bubble issues with glazes. This is not because they do not occur, it is because the appearance of typical glaze types are not affected by bubbles (and infact are often enhanced by them). But at low temperatures potters usually want to achieve good clarity in transparents and brilliance in a colors, so they find themselves in the same territory as the ceramic industry. An important way to do this is by using more frits (and the right firing schedules).

Adding iron to a clear glaze has cleared the micro-bubbles!

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

The glaze on the right is a transparent, G2926B, on a dark burning cone 6 body (Plainsman M390). On the left is the same glaze, but with 4% red iron oxide added. The entrained microbubbles are gone and the color is deep and much richer. It is not clear how this happens, but it is some sort of "fining" and is certainly beneficial. In other circumstances, we have seen big benefits with only 2% iron added.

Inbound Photo Links

Links

| Glossary |

Carbon trap glazes

A type of ceramc glaze. |

| Glossary |

LOI

Loss on Ignition is a number that appears on the data sheets of ceramic materials. It refers to the amount of weight the material loses as it decomposes to release water vapor and various gases during firing. |

| Glossary |

Glaze Blisters

Blistering is a common surface defect that occurs with ceramic glazes. The problem emerges from the kiln and can occur erratically in production. And be difficult to solve. |

| Glossary |

Surface Tension

In ceramics, surface tension is discussed in two contexts: The glaze melt and the glaze suspension. In both, the quality of the glaze surface is impacted. |

| Glossary |

Transparent Glazes

Every glossy ceramic glaze is actually a base transparent with added opacifiers and colorants. So understand how to make a good transparent, then build other glazes on it. |

| Glossary |

Drop-and-Soak Firing

A kiln firing schedule where temperature is eased to the top, then dropped quickly and held at a temperature 100-200F lower. |

| Glossary |

Ceramic Glaze Defects

Ceramic glaze defects include things like pinholes, blisters, crazing, shivering, leaching, crawling, cutlery marking, clouding and color problems. |

| Glossary |

Fining Agent

Individual tiny bubbles in a glaze melt can coalesce around the undissolved particles of a fining agent, the growing bubble swallowing others around it and finally exiting at the surface. |

| Tests |

Glaze Melt Fluidity - Ball Test

A test where a 10-gram ball of dried glaze is fired on a porcelain tile to study its melt flow, surface character, bubble retention and surface tension. |

| Firing Schedules |

Cone 6 Drop-and-Soak Firing Schedule

350F/hr to 2100F, 108/hr to 2200, hold 10 minutes, freefall to 2100, hold 30 minutes, free fall |

| By Tony Hansen Follow me on        |  |

Got a Question?

Buy me a coffee and we can talk

https://digitalfire.com, All Rights Reserved

Privacy Policy