| Monthly Tech-Tip | Feb 14-15, 2026 - Major Server Upgrade Done | No tracking! No ads! |

Calcia Matte

Calcia matte ceramic glazes are “crystal mattes” while magnesia mattes are “microstructure mattes”. They have a smoother surface but can also have finely textured, even frosty, feathery or sugary surfaces, depending cooling and crystalliztion.

Key phrases linking here: calcium matte, calcia mattes, calcia matte - Learn more

Details

This is the most common matteness mechanism in stoneware glazes. Calcia mattes are “crystal mattes” while magnesia mattes are “microstructure mattes”. CaO forms crystals because calcium fits very well into specific silicate crystal structures and not very well into a random glass network — so as the melt cools, the system lowers its energy by kicking Ca out of the glass and into ordered mineral crystals. When calcium oxide exists in excess in a melt, the process is enhanced. These crystallites scatter light and create a matte finish.

Calcia mattes are thus usually smoother, having a less silky or buttery surface than magnesia mattes. They can also have finely textured, even frosty, feathery or sugary surfaces, depending on the crystal development that has occurred.

Deeper dive into why CaO crystallizes so well:

CaO “wants” to form crystals because Ca²⁺ fits exceptionally well into stable calcium silicate and calcium aluminosilicate lattices, and as the glaze cools the glass becomes supersaturated in calcium, making crystal formation a lower-energy state than staying dissolved in the glass. Glaze melts are a disordered silicate network with flux ions (Ca²⁺, Na⁺, K⁺, Mg²⁺) sitting in the gaps. Some are “happy” staying dissolved in the glass, while others are “happier” forming specific, stable crystal lattices. Multiple properties give calcium a “Goldilocks” chemistry for the latter. An ionic size that fits silicate lattices perfectly to form minerals like wollastonite (CaSiO₃) and diopside (CaMgSi₂O₆). And also anorthite (CaAl₂Si₂O₈), it has a low nucleation barrier and forms readily (since glazes almost always contain Al2O3). So as the melt cools, it’s thermodynamically favorable for CaO + SiO₂ and/or Al₂O₃ to reorganize into those crystals instead of staying in the glass. Calcium is divalent (Ca²⁺), giving it an electrostatic pull on oxygen to nucleate and organize Si–O units into repeatable patterns. Finally, CaO has limited solubility in silicate glass at lower temperatures, thus, as temperature drops, the glass can’t “hold” as much CaO in solution, which triggers nucleation and crystal growth. By contrast, alkalis strongly prefer the glass phase, keeping the melt fluid and disordered. Likewise, Mg²⁺ is smaller and more tightly bound to oxygen, fitting better into the glass network itself (where it contributes to phase separation).

Related Information

Calcia vs Magnesia matte - Different mechanisms

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

This melt flow test was done at cone 6+ (without slow cooling) to demonstrate the difference in melt viscosity between a calcia matte (left) and a magnesia matte (right). In simplest terms, the former depends on a fluid melt to provide the needed mobility for tiny crystals to form during cooling, those crystals scatter the light and soften the surface to produce the matte effect. The latter requires a stiffer melt to help prevent leveling during cooling and host phase separation to produce a surface that scatters light.

Converting a glossy transparent glaze to a calcia matte

A ten-minute video to give glaze nerds goose bumps!

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Watch the G1214Z video to see me convert the G1214M cone 6 clear base into G1214Z cone 6 calcia matte using simple glaze chemistry and recipe logic. This first appeared in the Digitalfire desktop Insight instruction manual 30 years ago. It is an understatement to say that this process is interesting if you want to know more about glazes, their chemistry and recipe logic. Watch this video and see me adjust the recipe of my high-calcium transparent cone 6 glaze to convert it into a calcia matte. In an Insight-live.com account, the process is easy enough for anyone. We'll cut the Si:Al ratio, increase the CaO, maintain the thermal expansion for glaze fit and make the recipe shrinkage-adjustable using a mix of calcined kaolin and raw kaolin. We will even compare it with the High Calcium Semimatte from Mastering Glazes.

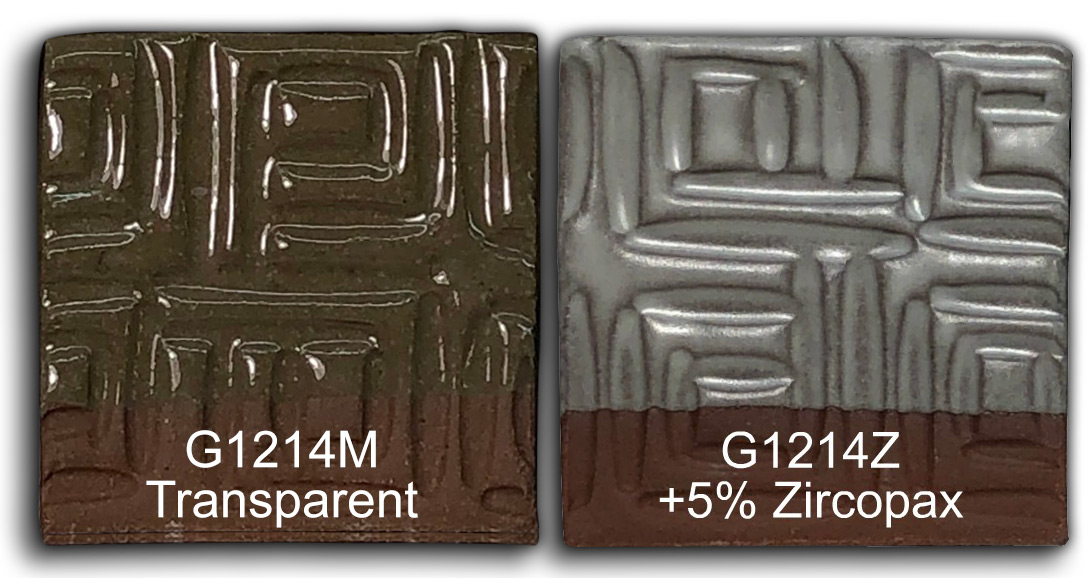

Partially and fully opacified cone 6 G1214Z1 matte glaze

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

This is the G1214Z1 calcia matte base (as opposed to the magnesia matte G2934). The clay is Plainsman M390. 5% Zircopax was added on the left (normally 10% or more is needed to get full opacity, the partially opaque effect highlight contours well). 5% tin oxide was added to the one on the right (tin is a more effective, albeit expensive opacifier in oxidation). The PLC6DS firing schedule was used.

Titanium Dioxide in a cone 6 calcia matte glaze

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

The glaze is G1214Z1 cone 6 base calcia matte on Plainsman M390 fired at cone 6 using the PLC6DS schedule. 5% titanium dioxide has been added. Titanium can create reactive glazes, like rutile, with no other colorants added. This effect also works well on matte surfaces, but the glaze needs good melt fluidity (that is good because functional mattes melt well). Calcia mattes host crystallization and work particularly well. Because titanium dioxide does not contain iron oxide lighter colors and better blues are possible compared to rutile (iron is still needed by it is coming from the body here). Like rutile, the effects are dependent on the cooling rate of the firing, slower cools produce more reactivity. Even application without drips is important (mixing as a thixotropic dipping glaze is best). This appearance also depends on using dark burning body or engobe.

Ravenscrag High Calcia Matte

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Courtesy of Jonathan Kirkendall

Oxidation fired speckled glaze!

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

The magnesia and calcia matte base glazes we have developed for electric firings have soft surfaces that rival the feel and utility of those achievable in reduction-fired dolomite mattes. By adding 0.2% granular manganese to M340 clay we can achieve this speckled aesthetic (outside of mug) using G2934 matte glaze.

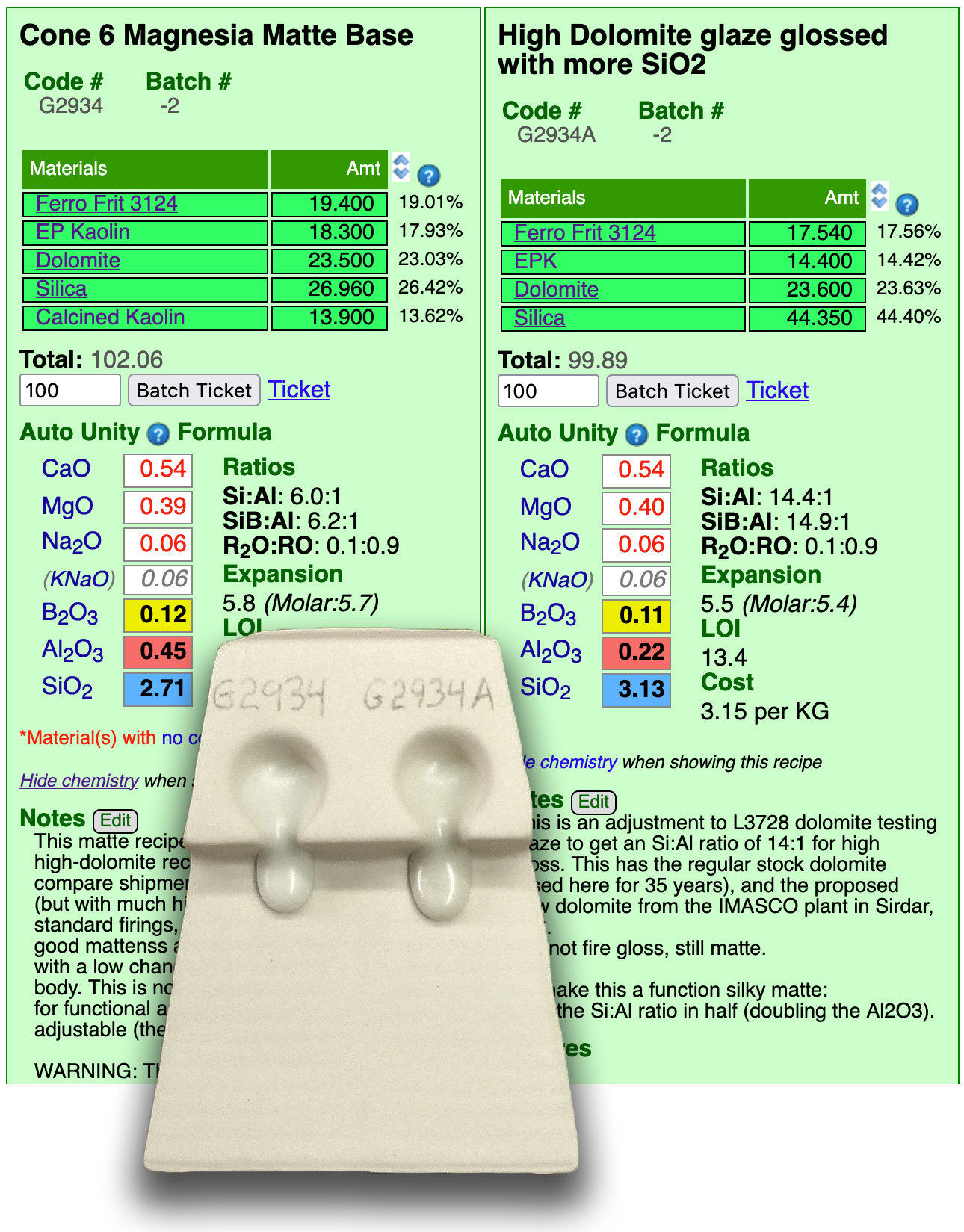

G2934 plus 10% silica actually flows more

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Until now, I thought that magnesia matte glazes need high Al2O3 and a low Si:Al ratio. But this melt flow test suggests otherwise. The cone 6 glaze on the left (A) is close to my usual target of 0.4 MgO, 0.1 B2O3 and a ratio of 6:1. It melts well but does not run. The typical MgO mechanism of phase separation and micro-wrinkling of the surface thrives here. But glaze B has a super-high ratio of 14:1, very low Al2O3 and a super-high percentage of silica in the recipe. Yet it runs better and is still matte (although slightly less so). How?

It seems I stumbled onto a shift between two different types of matte surfaces. Dropping the Al2O3 to 0.22 and spiking the SiO2 has moved from an alumina matte to a silica matte. B-mattness is likely caused by saturation and devitrification. Even though SiO2 is a glass former, it needs enough "alumina-scaffolding" to stay in a stable, disordered glass state. By cutting the Al2O3 in half and creating a massive surplus of SiO2, I’ve weakened the "glue" that keeps the MgO and CaO busy in the glass matrix (so they find each other and precipitate out as crystals), likely as diopside (CaMgSi2O6) or enstatite (MgSiO3). High-magnesia/low-alumina melts can also undergo phase separation into silica-rich and flux-rich liquids (like oil and vinegar), also creating a "micro-wrinkled" or mottled texture.

The second one flows more because alumina is incredibly refractory, creating viscous melts. By dropping it so much, we have removed the "brakes." Even with added silica, the balance has shifted in favor of the fluxes.

Links

| Glossary |

Magnesia Matte

Magnesia matte ceramic glazes are “microstructure mattes” while calcia mattes are “crystal mattes”. They have a micro-wrinkle surface that forms from a high viscosity melt and microscopic phase separation, both of which prevent levelling on freezi |

| By Tony Hansen Follow me on        |  |

Got a Question?

Buy me a coffee and we can talk

https://digitalfire.com, All Rights Reserved

Privacy Policy