| Monthly Tech-Tip | Feb 14-15, 2026 - Major Server Upgrade Done | No tracking! No ads! |

A Low Cost Tester of Glaze Melt Fluidity

A One-speed Lab or Studio Slurry Mixer

A Textbook Cone 6 Matte Glaze With Problems

Adjusting Glaze Expansion by Calculation to Solve Shivering

Alberta Slip, 20 Years of Substitution for Albany Slip

An Overview of Ceramic Stains

Are You in Control of Your Production Process?

Are Your Glazes Food Safe or are They Leachable?

Attack on Glass: Corrosion Attack Mechanisms

Ball Milling Glazes, Bodies, Engobes

Binders for Ceramic Bodies

Bringing Out the Big Guns in Craze Control: MgO (G1215U)

Can We Help You Fix a Specific Problem?

Ceramic Glazes Today

Ceramic Material Nomenclature

Ceramic Tile Clay Body Formulation

Changing Our View of Glazes

Chemistry vs. Matrix Blending to Create Glazes from Native Materials

Concentrate on One Good Glaze

Copper Red Glazes

Crazing and Bacteria: Is There a Hazard?

Crazing in Stoneware Glazes: Treating the Causes, Not the Symptoms

Creating a Non-Glaze Ceramic Slip or Engobe

Creating Your Own Budget Glaze

Crystal Glazes: Understanding the Process and Materials

Deflocculants: A Detailed Overview

Demonstrating Glaze Fit Issues to Students

Diagnosing a Casting Problem at a Sanitaryware Plant

Drying Ceramics Without Cracks

Duplicating Albany Slip

Duplicating AP Green Fireclay

Electric Hobby Kilns: What You Need to Know

Fighting the Glaze Dragon

Firing Clay Test Bars

Firing: What Happens to Ceramic Ware in a Firing Kiln

First You See It Then You Don't: Raku Glaze Stability

Fixing a glaze that does not stay in suspension

Formulating a body using clays native to your area

Formulating a Clear Glaze Compatible with Chrome-Tin Stains

Formulating a Porcelain

Formulating Ash and Native-Material Glazes

G1214M Cone 5-7 20x5 glossy transparent glaze

G1214W Cone 6 transparent glaze

G1214Z Cone 6 matte glaze

G1916M Cone 06-04 transparent glaze

Getting the Glaze Color You Want: Working With Stains

Glaze and Body Pigments and Stains in the Ceramic Tile Industry

Glaze Chemistry Basics - Formula, Analysis, Mole%, Unity

Glaze chemistry using a frit of approximate analysis

Glaze Recipes: Formulate and Make Your Own Instead

Glaze Types, Formulation and Application in the Tile Industry

Having Your Glaze Tested for Toxic Metal Release

High Gloss Glazes

Hire Us for a 3D Printing Project

How a Material Chemical Analysis is Done

How desktop INSIGHT Deals With Unity, LOI and Formula Weight

How to Find and Test Your Own Native Clays

I have always done it this way!

Inkjet Decoration of Ceramic Tiles

Is Your Fired Ware Safe?

Leaching Cone 6 Glaze Case Study

Limit Formulas and Target Formulas

Low Budget Testing of Ceramic Glazes

Make Your Own Ball Mill Stand

Making Glaze Testing Cones

Monoporosa or Single Fired Wall Tiles

Organic Matter in Clays: Detailed Overview

Outdoor Weather Resistant Ceramics

Painting Glazes Rather Than Dipping or Spraying

Particle Size Distribution of Ceramic Powders

Porcelain Tile, Vitrified Tile

Rationalizing Conflicting Opinions About Plasticity

Ravenscrag Slip is Born

Recylcing Scrap Clay

Reducing the Firing Temperature of a Glaze From Cone 10 to 6

Setting up a Clay Testing Program in Your Company or Studio

Simple Physical Testing of Clays

Single Fire Glazing

Soluble Salts in Minerals: Detailed Overview

Some Keys to Dealing With Firing Cracks

Stoneware Casting Body Recipes

Substituting Cornwall Stone

Super-Refined Terra Sigillata

The Chemistry, Physics and Manufacturing of Glaze Frits

The Effect of Glaze Fit on Fired Ware Strength

The Four Levels on Which to View Ceramic Glazes

The Majolica Earthenware Process

The Potter's Prayer

The Right Chemistry for a Cone 6 Magnesia Matte

The Trials of Being the Only Technical Person in the Club

The Whining Stops Here: A Realistic Look at Clay Bodies

Those Unlabelled Bags and Buckets

Tiles and Mosaics for Potters

Toxicity of Firebricks Used in Ovens

Trafficking in Glaze Recipes

Understanding Ceramic Materials

Understanding Ceramic Oxides

Understanding Glaze Slurry Properties

Understanding the Deflocculation Process in Slip Casting

Understanding the Terra Cotta Slip Casting Recipes In North America

Understanding Thermal Expansion in Ceramic Glazes

Unwanted Crystallization in a Cone 6 Glaze

Using Dextrin, Glycerine and CMC Gum together

Volcanic Ash

What Determines a Glaze's Firing Temperature?

What is a Mole, Checking Out the Mole

What is the Glaze Dragon?

Why Textbook Glazes Are So Difficult

Working with children

Where do I start in understanding glazes?

Description

Break your addiction to online recipes that don't work or bottled expensive glazes that you could DIY. Learn why glazes fire as they do. Why each material is used. How to create perfect dipping and brushing properties. Even some chemistry.

Article

Likely you have already watched lots of Youtube videos and found there are many ways to approach ceramics. Hobbyists and artists often think of clay as a "canvas" and glazes as "paints", they imagine showcasing their painting skills with artistic designs, they enter with an expectation of few issues and creating the exact colors and surfaces they want (from the expensive bottled glazes they assume won't craze or shiver on their bodies). Others enter with the desire to mix their own clays, formulate their own glazes, build their own kilns and they relish the new things learned with each firing. These often embark on mixing recipes found on Pinterest, Glazy or Facebook, hoping they will somehow magically work.

In industry the prevailing culture is more and more toward dependence on suppliers, getting by with the least knowledge possible. We are often amazed at how little knowledge technicians working in huge factories sometimes have!

You may have realized by now that this site is dedicated to fighting these cultures (which we personify as "the glaze dragon"). Understanding glazes better can empower you in many ways.

- Understand the difference between a base-coat dipping glaze, a dipping glaze and a brushing glaze.

- Find good glossy, matte and fluid glossy base recipes in your temperature range. Work with these and adjust them to fit your clay. Substitute your materials and fix other issues (e.g. poor suspension or application properties, crazing or shivering, excessive drying shrinkage, micro-bubbling, crystallization). Use them pure (or with added zircon to whiten and make them opaque) as liner glazes. Then add colorants and variegators for decorative surfaces. Examples of bases we developed this way are G2934Y, G2926B and G3806C (links below or findable on google).

- Be slow to bring a new recipe into your operation unless you understand it. Could you add its mechanism (colorants, opacifiers and variegators) to a base recipe you already have?

- Learn more about the materials you are using. Are they there to make the glaze melt? To color it? To suspend it in the bucket? To variegate the color or opacify the glass? To make it crystallize on firing? To matte it? Have they been well chosen to source the chemistry needed? Etc.

- Learn about how to make a slurry suspend well in the bucket (by controlling its specific gravity and thixotropy). This is super important, the vast majority of potters do not know how to do it. The rheological properties (specific gravity, viscosity, thixotropy) of almost any glaze slurry can be fine-tuned so that it will go on evenly without drips and dry quickly and to the right thickness on dense or porous bisque ware.

- Practice spotting the 'mechanisms' in recipes. What materials in the recipe make them fire the way they do? When you see recipes, mentally disassemble them into their base, additions and mechanisms.

- Although you are not a chemist you likely realize that fired glaze properties like gloss, color, thermal expansion, hardness, melting temperature, etc. are most directly related to the chemistry. What exactly do we mean by "glaze chemistry"? It means simply that you view your glazes as made of oxides like SiO2, Al2O3, Na2O, etc. and your materials as suppliers of them. The oxide makeup of a glaze is called a "formula". There are about 10 oxides to learn about, your raw materials contribute them. Using glaze chemistry (e.g. an account at insight-live.com) you can calculate the formula of a recipe.

- Learn to be demanding. Do no accept naked (undocumented) recipes. Do not accept problems like crazing, scratching, leaching, micro-bubble clouding, settling in the bucket. Learn to fix them. Don't work with temperamental glazes (e.g. rutile blues, high Gerstley Borate jellies) unless you understand the reason to tolerate them. Do not accept high reject rates.

- Do not waste time, be willing to work. Do lots of testing. Most of your tests should be smaller changes to recipes you have so you can learn something. Do not be afraid of failure, it teaches us.

- Document. Document your failures. With good pictures. Use an account at insight-live.com to record every recipe you make, every test firing, every project. You will find the ability to see recipes side-by-side with pictures, data, notes and chemistry invaluable in determining what changes to make next. Your account will also immerse you in reference material so you will be learning constantly.

- And easy on-ramp: Watch my timeline at digitalfire.com. Sign up for my monthly technical tip. Follow me on social.

Are you concerned about producing safe, non-leaching glazes?

It is about balance in the chemistry, not saturating it with heavy metals, about firing in the way appropriate for the recipe, about liner glazing. About knowing how to adjust. It’s not rocket science. It’s about not trusting anything with significant percentages of colorants (or things like barium carbonate, lithium carbonate), even commercial glazes, without doing simple leach testing. Just get started taking the new approaches mentioned here and you will become opinionated about leaching in no time!

Are you at a school, art center or club?

- Does your school have a few recipes that are treated as if they were "dropped from heaven"? There is plenty of information here to help you improve them. Learn how to determine if you need to approach the problem on one or more of the material, process or chemistry levels. It is also likely there are some are leaching metals. And very likely crazing.

- There is a good chance that every single bucket of glaze is improperly mixed (so it does not suspend well, does not go on evenly or dry quickly without cracks). Read the article on Thixotropy (link below). If you can turn those rock-hard-on-the-bottom buckets into the most silky and easy-to-use glaze they have ever seen you will be a hero!

- If you teach a class first learn to teach your students to understand materials and the physical properties they bring to the glaze slurry. Then introduce the concept of chemistry, how the materials source it to the glaze recipe and how it is the most important a determinant of fired glaze properties. Then teach them about rheology and how to identify a mechanism.

- Learn to make your own jars of paintable glazes. These are gummed and desirable in many situations (and much less expensive for bright colors).

Are you at a factory?

- Do consultants or supplier reps visit your company and mess about with your glazes but never stay long enough to explain anything or to really understand your issues? Learn the chemistry and physics yourself and take control. Study the contribution of each glaze material. Don't use frits that suppliers will not provide chemistry data for.

- Wait for a crisis with a glaze, the solution to which is being mismanaged by narrow material-level or supplier-dependent thinking. Solve it using chemistry. Or thorough and documented testing (use the Trouble-Shooting section here for ideas).

- Does your company or organization have far too many different glaze recipes and stock too many materials? Learn to view materials as oxide suppliers. Study what each oxide does. Review the info here on how to substitute different materials yet supply the same oxides. Read about base glazes and how to identify mechanisms so you can adopt a base-with-variations approach. In the end the company will have fewer recipes to manage.

- If you use commercial glazes and either cannot justify the expense anymore or cannot solve problems for lack of content information, then learn about base glazes and develop or adjust one to fit your body. Then experiment with stain and opacifier additions and study chemistry issues surrounding colors that do not develop as expected.

Places to start

- https://digitalfire.com: The information in the articles, oxides, materials and glossary sections here.

- If you are new to the concept of glaze chemistry start with an article on one of our base glaze recipes and learn why each material is there. Then learn to appreciate the value of having a base glaze that is adjustable, has the right gloss and melting temperature, has good application properties, fits your clay body, etc.

- Get an account at https://insight-live.com and start entering the recipes you know and use already. Learn how to make it show the chemistry and compare them side-by-side. Document everything you know and learn about them. With pictures.

If you are going to make ceramic ware, put good glazes on it. Remember, a glaze is a lot more than one that just has a pleasing fired appearance. There is no one-glaze-that-works-for-everyone. We cater to people that want to start out right, or have been kicked around long enough that they are ready to learn why, they want to "understand". You will never likely get the glazes you really want until you formulate or adapt them yourself.

Related Information

This is crazing. On functional ware. Not good.

AI generated with the prompt: A crazed glaze on a stoneware pottery mug.

AI generated with the prompt: A crazed glaze on a stoneware pottery mug.This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

This glaze is "stretched" on the clay so it cracks. When the lines are close together like this it is more serious. If the effect is intended, it is called "crackle" (but no one should intend this on functional ware). Potters, hobbyists and artists invariably bump into this issue whether using commercial glazes or making their own.

"Art language" solutions don't work, at least some technical words are needed to understand it. Crazing is a mismatch in the thermal expansions of glaze and body. Most ceramics expand slightly on heating and contract on cooling. The amount of change is very small, but ceramics are brittle and glazes are rigidly attached. If they are stretched on the ware cracks will occur to relieve the stress (usually during cooling in the firing but sometimes much later). All glaze and body manufacturers advise against crazing on functional ware.

A high feldspar glaze is settling, running and crazing. What to do?

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

The original cone 6 recipe, WCB, fires to a beautiful brilliant deep blue green (shown in column 2 of this Insight-live screen-shot). But it is crazing and settling badly in the bucket. The crazing is because of high KNaO (potassium and sodium from the high feldspar). The settling is because there is almost no clay in the recipe. Adjustment 1 (column 3 in the picture) eliminates the feldspar and sources Al2O3 from kaolin and KNaO from Frit 3110 (preserving the glaze's chemistry). To make that happen the amounts of other materials had to be juggled. But the fired test revealed that this one, although very similar, is melting more (because the frit releases its oxides more readily than feldspar). Adjustment 2 (column 4) proposes a 10-part silica addition. SiO2 is the glass former, the more a glaze will accept without losing the intended visual character, the better. The result is less running and more durability and resistance to leaching.

Commercial supposedly safe glazes leaching. A liner glaze is needed.

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Three cone 6 commercial bottled glazes have been layered. The mug was filled with lemon juice overnight. The white areas indicate leaching has occurred! Why? Glazes need high melt fluidity to produce reactive surfaces like this. While such normally tend to leach metals, supposedly the manufacturers were able to tune the chemistry enough to pass tests. But the overlaps interact, like drug interactions they are new chemistries. Cobalt is clearly leaching. What else? We do not know, these recipes are secret. It is better to make your own transparent or white liner glaze (either as a dipping glaze or brushing glaze). Better to know the recipe to have assurance of adherence to basic recipe limits.

Are commercial glazes really guaranteed food safe? When manufacturers claim adherence to standards like ASTM D-4236 what are they saying? The small amounts of liquid glazes are safe for the artist to brush on. They are not making claims about leaching on finish ware.

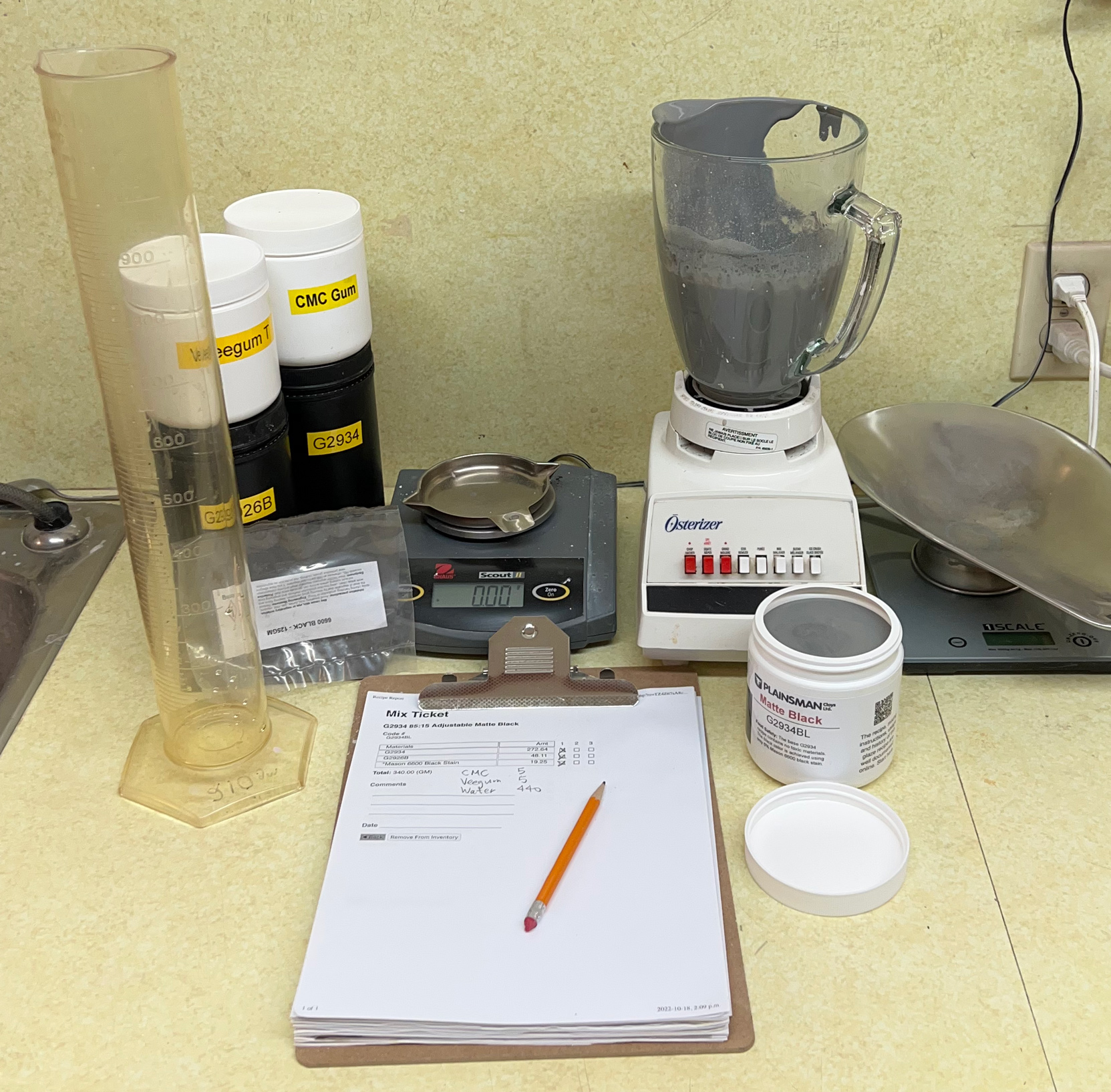

Here is my setup to make brushing glazes and underglazes by-the-jar

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Although I promote DIY dipping glazes, you can also make DIY brushing glazes. Let's make a low SG version of G2934BL. Weigh out a 340g batch of dipping glaze powder. Include 5g Veegum (to gel the slurry to enable more than normal water) and 5g CMC gum (to slow drying and impart brushing properties). Measure 440g of water initially (adjusting later if needed). Shake-mix all the powder in a plastic bag. Pour it into the water, which is blender mixing on low speed, and finish with 20 seconds on high speed. This just fills a 500ml jar. In subsequent batches, I adjust the Veegum for more or less gel, the CMC for slower or faster drying and the water amount for thicker or thinner painted layers. Later I also assess whether the CMC gum is being degraded by microbial attack - often evident if the slurry thins and loses its gel. Dipping glaze recipes can and do respond differently to the gums. Those having little clay content work well (e.g. reactive and crystalline glazes). If bentonite is present it is often best to leave it out. Recipes having high percentages of ball clay or kaolin might work best with less Veegum. Keeping good notes (with pictures) is essential to reach the objective here: Good brushing properties. We always use code-numbering (in our group account at Insight-live.com) and write those on the jars and test pieces. This is so worthwhile doing that I make quality custom labels for each jar!

Better to mix your own cover glazes for production?

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Yes. In this case the entire outside and inside of the mug need an evenly applied coat of glaze. For hobby this makes sense. But in production cover brushing makes less sense. The right pail has 2 gallons of G2934Y base with 10% Cerdec yellow stain: $135. Cost of brushing jars with the same amount: $600+! And each jar logs 10-15 minutes painting time plus waiting between coats. The one in the pail is a true dipping glaze (unlike many commercial ones that dry slowly and drip-drip-drip). This one dries immediately after dipping in a perfectly even layer (if mixed according to our instructions). And a bonus: This pail can be converted to brushing or base-layering versions using CMC gum.

Dip-glazing vs. brush-on glazing: Which gives the more even surface?

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

This is a clear glaze (G2931K) with 10% purple stain (Mason 6385). The mugs are cone 03 porcelain (Zero3). The mug on the left was dipped (at the bisque stage) into a slurry of the glaze (having an appropriate specific gravity and thixotropy). The glaze dried in seconds. The one on the right was painted on (two layers). Like any paint-on glaze, it contains gum (1% CMC). Each layer required several minutes of application time and fifteen minutes of drying time. Yet it is still not evenly applied.

Brush-on commercial pottery glazes are perfect? Not quite!

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Brushing glazes are great sometimes. But they would be even greater if the recipe was available. Then it would be possible to make it if they decide to discontinue the product. Or if your retailer does not have it. Or to make a dipping glaze version for all the times when that is the better way to apply. The glaze manufacturer did not consider glaze fit with your clay body, if they work well together it is by accident. But if you have transparent and matte base recipes that that work on your clay body then adding stains, variegators and opacifiers is easy. And making a brushing glaze version of any of them. Don't have base recipes??? Let's get started developing them with an account at insight-live.com (and the know-how you will find there)!

Think the idea of mixing your own glazes is dead? Nope!

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

These are two pallets (of three) that went on a semi-trailer load to a Plainsman Clays store in Edmonton this week. They are packed with hundreds of bags of powders used to mix glazes. More and more orders for raw ceramic materials are coming in all the time. Maybe you are using lots of bottled glazes but for a cover or a liner glaze it is better to mix your own. And cheaper! And there are lots of recipes and premixed powders here to do it. One of the big advantages is that when you dip ware into a properly mixed slurry it goes on perfectly even, does not run and dries on the bisque in seconds. No bottled glaze can do that.

What can you do using glaze chemistry? More than you think!

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

There is a direct relationship between the way ceramic glazes fire and their chemistry. These green panels in my Insight-live account compare two glaze recipes: A glossy and matte. Grasping their simple chemistry mechanisms is a first step to getting control of your glazes. To fixing problems like crazing, blistering, pinholing, settling, gelling, clouding, leaching, crawling, marking, scratching, powdering. To substituting frits or incorporating available, better or cheaper materials while maintaining the same chemistry. To adjusting melting temperature, gloss, surface character, color. And identifying weaknesses in glazes to avoid problems. And to creating and optimizing base glazes to work with difficult colors or stains and for special effects dependent on opacification, crystallization or variegation. And even to creating glazes from scratch and using your own native materials in the highest possible percentage.

Common dipping glazes converted to jars of high SG brushing

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

These are cone 6 Alberta Slip recipes that have been brushed onto the outsides of mugs (three coats gave very thick coverage). Recipes are GA6-C Rutile Blue on the outside of the left mug, GA6-F Alberta Slip Oatmeal on the outside of the center mug and GA6-F Oatmeal over G2926B black on the outside of the right mug). These one-pint jars were made using 500g of powder, 280g of water and 75g of Laguna CMC gum solution (equivalent of adding 1% powdered CMC). Because no Veegum is being used this blender mixes to a slurry of high 1.6 specific gravity (for thicker coverage per coat than commercial glazes having much more water). This approach is good for recipes high in Alberta Slip. The gum removes the need for roasting part of it, reduces the water needed and the plasticity of the Alberta Slip helps suspend the slurry.

Commercial glazes on decorative surfaces, your own on food surfaces

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

These cone 6 porcelain mugs are hybrid. Three coats of a commercial glaze painted on the outside (Amaco PC-30) and my own liner glaze, G2926B, poured in and out on the inside. When commercial glazes (made by one company) fit a stoneware or porcelain (made by another company) it is by accident, neither company designed for the other! For inside food surfaces make or mix a liner glaze already proven to fit your clay body, one that sanity-checks well (as a dipping glaze or a brushing glaze). In your own recipes you can use quality materials that you know deliver no toxic compounds to the glass and that are proportioned to deliver a balanced chemistry. Read and watch our liner glazing step-by-step and liner glazing video for details on how to make glazes meet at the rim like this.

Here is a good start to doing serious ceramic production at home

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

This is what you need to be independent, to create your own manufacturing company in your garage in 2021 Some of the prices are "instead of" rather than additive. There are many approaches to glazes, the more you are willing to learn the better you will be able to make your own (and save a lot). We recommend the cone 6 range using a small test kiln (like this 220v ConeArt GX119, don't scrimp on this, go for quality and the practicality of a Genesis controller). A kiln you can fire often and inexpensively is a key enabler to learning, developing techniques, products, designs, durable and decorative surfaces, solving problems. It can be fired multiple times a day. And it is big enough for mugs and similar sizes. It will get you into the habit of using some of your creativity for experimenting. It will give you the successes early on that will inspire you to press on learning. When you are ready, then get a big kiln and hit-the-ground-running. This potter's wheel is the best available and will last a lifetime, these often appreciate in value over time. And, build yourself a good plaster table. You will use it constantly. Not shown here is a propeller mixer, also an important tool. And you will need a sink equipped with a sink trap (Gleco Trap).

Tried and True recipes. Really?

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Books and web pages with flashy pictures are the centrepiece of an addiction-ecosystem to recipes that often just don't work. Maybe these are "tried" by a lot of people. But are they "true"? Most are so-called "reactive glazes", outside normal practice - to produce visual interest they run, variegate, crystallize, pool, break, tint, go metallic, etc. But this happens at a cost. And inside special procedures and firing schedules that need explaining. It is not obvious these are understood by the recipe authors or sharers. And these recipes are dated and contain troublesome and unavailable materials. We use frits now to source boron. Stains are superior to raw colorants, even in glazes like this. Many of these will craze badly. And many will not suspend in the bucket. And will run during firing. Reactive glazes have other common issues: Blistering, leaching, cutlery marking, fuming. Trying colors in differing amounts in different base recipes is a good idea. But the project is most beneficial when it shows color response in terms of quality recipes of contrasting chemistries. The point of all of this: Understand a few glazes and develop them, rather than throwing spaghetti against the wall hoping something sticks. Commercial reactive glazes are an alternative also.

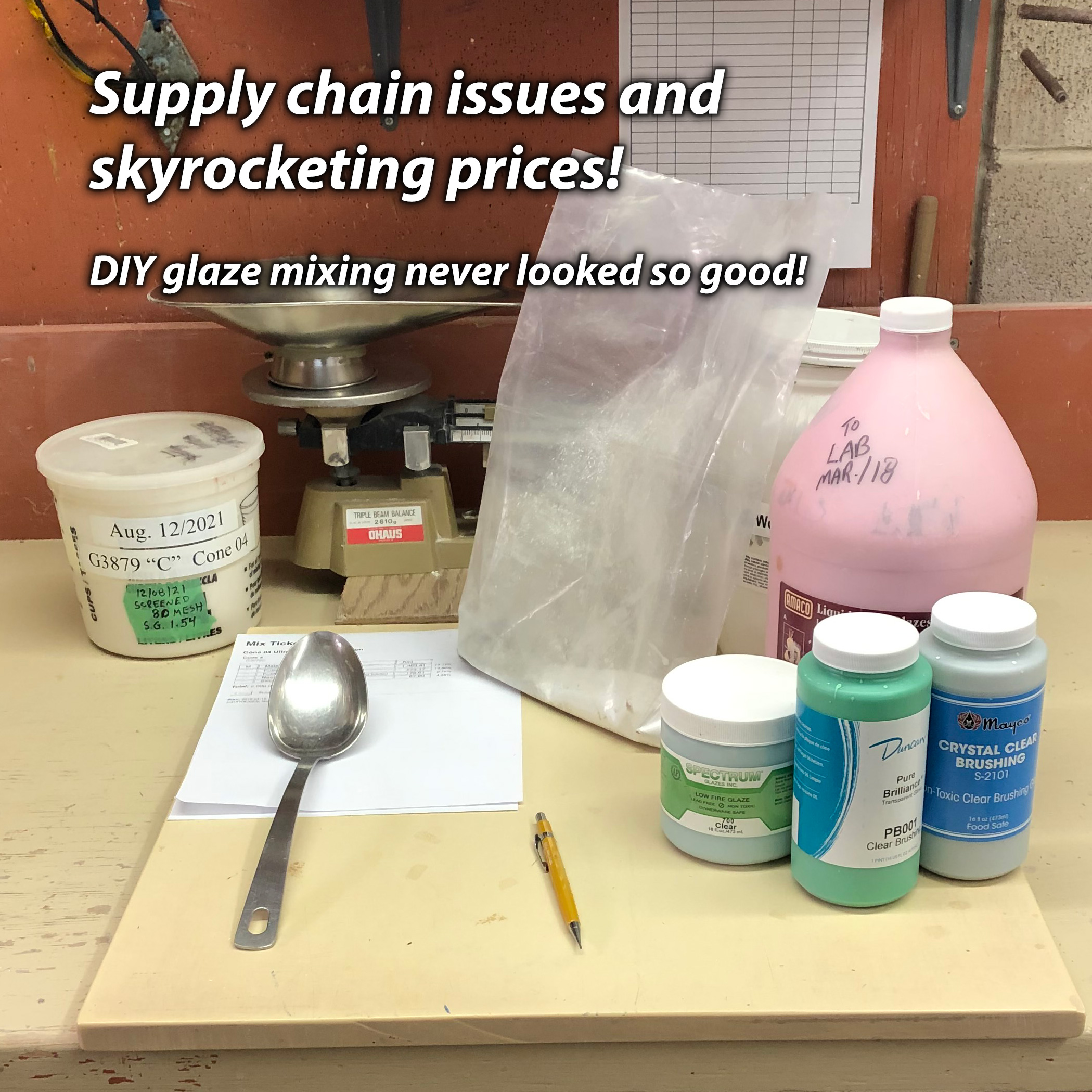

Global supply chain issues? Learn to mix and adjust your own bodies, glazes

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Material prices are sky rocketing. And, the more complex your supplier's supply chain the more likely they won't be able to deliver. How can you adapt to coming disruption, even turn it into a benefit? Learn to create base recipes for your glazes and even clay bodies. Learn now how to substitute frits and other materials in glazes (get the chemistry of frits you use now so you are ready). Even better: Learn to see your glaze as an oxide formula. Then calculate formula-to-batch to use whatever materials you can get. Learn how to adjust glazes for thermal expansion, temperature, surface, color, etc. And your clay bodies? Develop an organized physical testing regimen now to accumulate data on their properties, learn to understand how each material in the recipe contributes to those properties. Armed with that data you will be able to adjust recipes to adapt to changing supplies.

When Supply Chains Broke, Prices Soared.

We haven’t forgotten. Time for DIY!

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Material prices began skyrocketing during COVID. No one is affected more than prepared glaze manufacturers; they have complex supply chains that affect not only price but also availability and consistency of their products. Now might be the time for DIY, to start learning how to weigh out the ingredients to make at least some of your own, especially brushing glazes. You could be armed with good base recipes that fit your clay bodies, without crazing or shivering, by design, not by accident, as with commercial products. And you will be more resilient to supply issues. Add stains, opacifiers and variegators to the bases to make anything you want. Admittedly, ingredients in your recipes can also become unavailable! But DIY give you options. When you "understand" glaze ingredients and what each contributes to the recipe and oxide chemistry, you are equipped to go well beyond weathering material supply issues. You will improve recipes at the same time as adjusting them to accommodate alternative materials. It is not rocket science; it is just work accompanied by organized record-keeping and good labelling.

Is the N505 cone 6 matte glaze recipe what you think it is?

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

This recipe is from page 2 of the booklet: "15 Tried & True Cone 6 Glaze Recipes". Click the following code, G3955, to see more information on how it compares with G2934 and G1214Z1 mattes. This flow test and these test tiles were in the same kiln, fired at cone 6 using our PLC6DS schedule. The defining characteristic of N505 is its extreme melt fluidity - it runs because it is overtired at cone 6. Still, the surface on the tile (lower right) is arguably more interesting than G2934. Some felt pen marking reveals why: The micro surface is much rougher. To its credit, although it does stain easier, it can still be cleaned with effort.

From the chemistry, shown on Insight-Live side-by-side screenshot. It has very low Al2O3 and SiO2 - that turns on some red and yellow lights. One could hope to have melt fluidity and great functionality, but they pretty well never go together. This glaze should fire glossy - the 6% magnesium carbonate is the mechanism of the matteness - MagCarb is super refractory, it may not be dissolving in the. melt. The glaze should cutlery mark (although it seemed hard in our testing). Most important, low Si:Al levels always carry the risk of leaching - exercise caution adding any significant percentage of heavy metal pigments. Crazing is another possible issue over melted glaze.

Click here for case-studies of Insight-Live fixing problems

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

You will see examples of replacing unavailable materials (especially frits), fixing various issues (e.g. running, crazing, settling), making them melt more, adjusting matteness, etc. Insight-Live has an extensive help system (the round blue icon on the left) that also deals with fixing real-world problems and understanding glazes and clay bodies.

Another compelling reason for DIY casting bodies and glazes

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

These are four different cone 6 commercial glazes made by a popular US manufacturer. The body is a cone 6 casting porcelain made by another popular manufacturer. They are all crazing! This is visible because the glaze is transparent, but most often it is much more difficult to see. Guess what many people are doing? Ignoring the problem and selling the ware! Assuming you are not one of them - which company is at fault? Neither. They cannot assure their product fits those of others. Mid-fire porcelains craze glazes if they lack sufficient silica (20% is minimum) or don't vitrify. Unfortunately, the recipe of the porcelain is proprietary. Wait a minute - no, it isn't. These recipes are well-known. You already have a propeller mixer and scale to mix casting slip, why not mix your own porcelain from a recipe (e.g. L3778D or derivative)? Or, why not mix your own transparent brushing glaze or dipping glaze? Start with the G2926B recipe, it has lots of documentation, and the recipe can be adjusted to deal with fit issues on any clay body.

Are drippy glazes what pottery has come to?

AI-generated using prompt for drippy and layer glazed pottery typically displayed on social.

AI-generated using prompt for drippy and layer glazed pottery typically displayed on social.This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

There is an undeniable appeal to the bright colors of many commercial glazes. While nobody is recommending abandoning them and going all-in on DIY, there is an appeal to having more control. If you are a potter, hobbyist or small manufacturer, consider: Do we want customers eating and drinking from these kinds of glazes? This type of ware is often crazed (runny glazes do that, especially on bodies they were not designed to fit). These are also prime candidates for leaching the high percentages of the heavy metals they contain. All those drippy layers running and pooling on the insides can make pieces into glaze compression time bombs. For food surfaces, the glaze manufacturers want us using their recommended balanced, lightly colored products. Good news! These base recipes are also the easiest to make yourself. When did we get intimidated about mixing our own glazes anyway? No one has to go full mad scientist on DIY here. Research the common ingredients your supplier offers. Use recipes that pass a sanity test. Be a savvy consumer - these colored products are expensive and using them only on the outsides will cut your costs in half. Learn to add pigments to your base recipes and save even more. Then learn to make and use dipping glazes (not dripping glazes) and save time also.

Are you a doctor? Prescribe pottery!

AI generated with the prompt: A doctor prescribing pottery as a way to deal with stress, depression.

AI generated with the prompt: A doctor prescribing pottery as a way to deal with stress, depression.This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Everyone knows the calming effect of making pottery, no wonder it is recommended over chemicals as a way to deal with stress. Pottery acts as a form of meditation, creative therapy, and stress relief all rolled into one. Pottery offers a unique combination of benefits that can be therapeutic for those dealing with stress and depression:

-The process of working with clay demands focus and presence. The tactile nature of the material and the repetitive motions can help quiet the mind and induce a "flow state" where you lose track of time and worries.

-Pottery enables you to channel feelings into something tangible and beautiful, fostering a sense of accomplishment and control.

-Creative activities can lower stress hormones and the physical act of kneading and shaping clay can release tension.

-Successfully creating a piece of pottery, no matter how simple, can boost confidence and provide a sense of pride.

-Joining a pottery class or group can provide a sense of community and belonging, reducing feelings of isolation.

Our $50 pottery mugs vs. the $5 imports:

Do we just pretend this situation doesn't exist?

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Peggy-potter makes the hand-crafted mugs. Carla-coffee-drinker, needs a mug. This apparent perfect alignment goes off the rails when Carla compares Peggy's $50 price with premium imported mugs costing $5 (shown here). Especially when the imports emulate Peggy's techniques flawlessly while offering better durability and strength!

Peggy has to choose between hyping "kiln drops" on social or cutting costs. DIY techniques and supplies are a first option. Also mold-making and slip casting, even mixing her own casting slips. Mixing her own glazes, underglazes and engobes is the next step. Or learning to use less expensive bodies (e.g. with engobes).

Going DIY is not a big equipment investment. A plaster table, scale, mixing and batching table and a propeller mixer are the most important. And keeping good records (e.g. an account at insight-live.com). Following manufacturers on Instagram to see their glazing and forming techniques can help. Build throwing and drying skills by making hundreds of the same item. Consider: What you do affects other potters, prices cannot keep rising, or there will be no market.

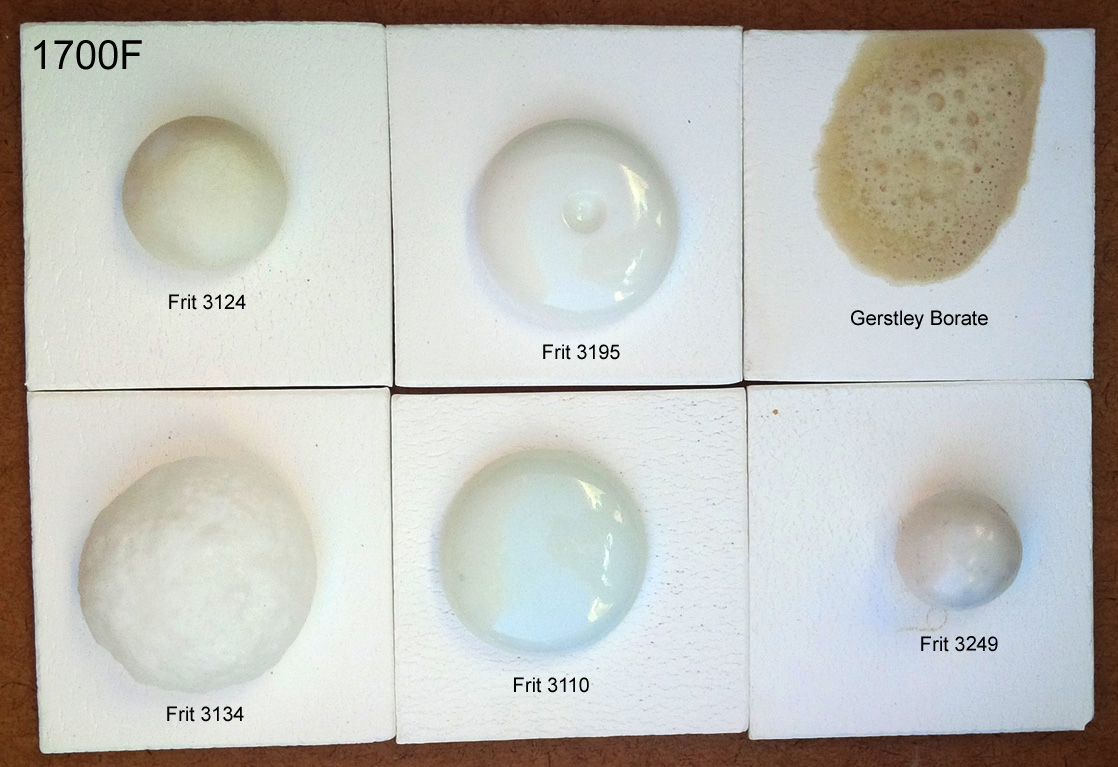

These common Ferro frits have distinct uses in traditional ceramics

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

I used Veegum to form 10 gram GBMF test balls and fired them at cone 08 (1700F). Frits melt really well, they do have an LOI like raw materials. These contain boron (B2O3), it is a low expansion super-melter that raw materials don’t have. Frit 3124 (glossy) and 3195 (silky matte) are balanced-chemistry bases (just add 10-15% kaolin for a cone 04 glaze, or more silica+kaolin to go higher). Consider Frit 3110 a man-made low-Al2O3 super feldspar. Its high-sodium makes it high thermal expansion. It works really well in bodies and is great to make glazes that craze. The high-MgO Frit 3249 (made for the abrasives industry) has a very-low expansion, it is great for fixing crazing glazes. Frit 3134 is similar to 3124 but without Al2O3. Use it where the glaze does not need more Al2O3 (e.g. already has enough clay). It is no accident that these are used by potters in North America, they complement each other well (equivalents are made around the world by others). The Gerstley Borate is a natural source of boron (with issues frits do not have).

In pursuit of a reactive cone 6 base that I can live with

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

These GLFL tests and GBMF tests for melt-flow compare 6 unconventionally fluxed glazes with a traditional cone 6 moderately boron fluxed (+soda/calcia/magnesia) base (far left Plainsman G2926B). The objective is to achieve higher melt fluidity for a more brilliant surface and for more reactive response with colorant and variegator additions (with awareness of downsides of this). Classified by most active fluxes they are:

G3814 - Moderate zinc, no boron

G2938 - High-soda+lithia+strontium

G3808 - High boron+soda (Gerstley Borate based)

G3808A - 3808 chemistry sourced from frits

G3813 - Boron+zinc+lithia

G3806B - Soda+zinc+strontium+boron (mixed oxide effect)

This series of tests was done to choose a recipe, that while more fluid, will have a minimum of the problems associated with such (e.g. crazing, blistering, low run volatility, susceptibility to leaching). As a final step the recipe will be adjusted as needed. We eventually evolved the G3806B, after many iterations settled on G3806E or G3806F as best for now.

Links

| Articles |

G1214M Cone 5-7 20x5 glossy transparent glaze

This is a base transparent glaze recipe developed for cone 6. It is known as the 20x5 or 20 by 5 recipe. It is a simple 5 material at 20% each mix and it makes a good home base from which to rationalize adjustments. |

| Articles |

G1916M Cone 06-04 transparent glaze

This is a frit based boron glaze that is easily adjustable in thermal expansion, a good base for color and a starting point to go on to more specialized glazes. |

| Articles |

Working with children

Go in with both eyes open if you are planning to work with clay with a group of children! A lot can go wrong but it can be unforgettable for them when it goes right. |

| Projects |

Oxides

|

| Projects |

Recipes

|

| Glossary |

Glaze Chemistry

Glaze chemistry is the study of how the oxide chemistry of glazes relate to the way they fire. It accounts for color, surface, hardness, texture, melting temperature, thermal expansion, etc. |

| Glossary |

Thixotropy

Thixotropy is a property of ceramic slurries of high water content. Thixotropic suspensions flow when moving but gel after sitting (for a few moments more depending on application). This phenomenon is helpful in getting even, drip-free glaze coverage. |

| Glossary |

Limit Formula

A way of establishing guideline for each oxide in the chemistry for different ceramic glaze types. Understanding the roles of each oxide and the limits of this approach are a key to effectively using these guidelines. |

| Glossary |

Glaze Recipes

Stop! Think! Do not get addicted to the trafficking in online glaze recipes. Learn to make your own or adjust/adapt/fix what you find online. |

| Glossary |

Ceramic Oxide

In glaze chemistry, the oxide is the basic unit of formulas and analyses. Knowledge of what materials supply an oxide and of how it affects the fired glass or glaze is a key to control. |

| Glossary |

Decomposition

In ceramic manufacture, knowing about the how and when materials decompose during firing is important in production troubleshooting and optimization |

| Glossary |

Mechanism

Identifying the mechanism of a ceramic glaze recipe is the key to moving adjusting it, fixing it, reverse engineering it, even avoiding it! |

| Glossary |

Brushing Glaze

Hobbyists and increasing numbers of potters use commercial paint-on glazes. It's convenient, there are lots of visual effects. There are also issues compared to dipping glazes. You can also make your own. |

| Glossary |

Rheology

In ceramics, this term refers to the flow and gel properties of a glaze or body suspension (made from water and mineral powders, with possible additives, deflocculants, modifiers). |

| Glossary |

Glaze Mixing

In ceramics, glazes are developed and mixed as recipes of made-made and natural powdered materials. Many potters mix their own, you can to. There are many advantages. |

| Glossary |

Reactive Glazes

In ceramics, reactive glazes have variegated surfaces that are a product of more melt fluidity and the presence of opacifiers, crystallizers and phase changers. |

| Glossary |

Digitalfire Taxonomy

|

| Glossary |

Base Glaze

Understand your a glaze and learn how to adjust and improve it. Build others from that. We have bases for low, medium and high fire. |

| URLs |

https://digitalfire.com/videos

Tutorial Videos at Digitalfire |

| Recipes |

G2926B - Cone 6 Whiteware/Porcelain transparent glaze

A base transparent glaze recipe created by Tony Hansen, it fires high gloss and ultra clear with low melt mobility. |

| Recipes |

G2934 - Matte Glaze Base for Cone 6

A base MgO matte glaze recipe fires to a hard utilitarian surface and has very good working properties. Blend in the glossy if it is too matte. |

| Recipes |

G2931K - Low Fire Fritted Zero3 Transparent Glaze

A cone 03-02 clear medium-expansio glaze developed from Worthington Clear. |

| By Tony Hansen Follow me on        |  |

Got a Question?

Buy me a coffee and we can talk

https://digitalfire.com, All Rights Reserved

Privacy Policy