| Monthly Tech-Tip | No tracking! No ads! | |

A Low Cost Tester of Glaze Melt Fluidity

A One-speed Lab or Studio Slurry Mixer

A Textbook Cone 6 Matte Glaze With Problems

Adjusting Glaze Expansion by Calculation to Solve Shivering

Alberta Slip, 20 Years of Substitution for Albany Slip

An Overview of Ceramic Stains

Are You in Control of Your Production Process?

Are Your Glazes Food Safe or are They Leachable?

Attack on Glass: Corrosion Attack Mechanisms

Ball Milling Glazes, Bodies, Engobes

Binders for Ceramic Bodies

Bringing Out the Big Guns in Craze Control: MgO (G1215U)

Can We Help You Fix a Specific Problem?

Ceramic Glazes Today

Ceramic Material Nomenclature

Ceramic Tile Clay Body Formulation

Changing Our View of Glazes

Chemistry vs. Matrix Blending to Create Glazes from Native Materials

Concentrate on One Good Glaze

Copper Red Glazes

Crazing and Bacteria: Is There a Hazard?

Crazing in Stoneware Glazes: Treating the Causes, Not the Symptoms

Creating a Non-Glaze Ceramic Slip or Engobe

Creating Your Own Budget Glaze

Crystal Glazes: Understanding the Process and Materials

Deflocculants: A Detailed Overview

Demonstrating Glaze Fit Issues to Students

Diagnosing a Casting Problem at a Sanitaryware Plant

Drying Ceramics Without Cracks

Duplicating Albany Slip

Duplicating AP Green Fireclay

Electric Hobby Kilns: What You Need to Know

Fighting the Glaze Dragon

Firing Clay Test Bars

Firing: What Happens to Ceramic Ware in a Firing Kiln

First You See It Then You Don't: Raku Glaze Stability

Fixing a glaze that does not stay in suspension

Formulating a body using clays native to your area

Formulating a Clear Glaze Compatible with Chrome-Tin Stains

Formulating a Porcelain

Formulating Ash and Native-Material Glazes

G1214M Cone 5-7 20x5 glossy transparent glaze

G1214W Cone 6 transparent glaze

G1214Z Cone 6 matte glaze

G1916M Cone 06-04 transparent glaze

Getting the Glaze Color You Want: Working With Stains

Glaze and Body Pigments and Stains in the Ceramic Tile Industry

Glaze Chemistry Basics - Formula, Analysis, Mole%, Unity

Glaze chemistry using a frit of approximate analysis

Glaze Recipes: Formulate and Make Your Own Instead

Glaze Types, Formulation and Application in the Tile Industry

Having Your Glaze Tested for Toxic Metal Release

High Gloss Glazes

Hire Us for a 3D Printing Project

How a Material Chemical Analysis is Done

How desktop INSIGHT Deals With Unity, LOI and Formula Weight

How to Find and Test Your Own Native Clays

I have always done it this way!

Inkjet Decoration of Ceramic Tiles

Is Your Fired Ware Safe?

Leaching Cone 6 Glaze Case Study

Limit Formulas and Target Formulas

Low Budget Testing of Ceramic Glazes

Make Your Own Ball Mill Stand

Making Glaze Testing Cones

Monoporosa or Single Fired Wall Tiles

Organic Matter in Clays: Detailed Overview

Outdoor Weather Resistant Ceramics

Painting Glazes Rather Than Dipping or Spraying

Particle Size Distribution of Ceramic Powders

Porcelain Tile, Vitrified Tile

Rationalizing Conflicting Opinions About Plasticity

Ravenscrag Slip is Born

Recylcing Scrap Clay

Reducing the Firing Temperature of a Glaze From Cone 10 to 6

Setting up a Clay Testing Program in Your Company

Simple Physical Testing of Clays

Single Fire Glazing

Soluble Salts in Minerals: Detailed Overview

Some Keys to Dealing With Firing Cracks

Stoneware Casting Body Recipes

Substituting Cornwall Stone

Super-Refined Terra Sigillata

The Effect of Glaze Fit on Fired Ware Strength

The Four Levels on Which to View Ceramic Glazes

The Majolica Earthenware Process

The Potter's Prayer

The Right Chemistry for a Cone 6 MgO Matte

The Trials of Being the Only Technical Person in the Club

The Whining Stops Here: A Realistic Look at Clay Bodies

Those Unlabelled Bags and Buckets

Tiles and Mosaics for Potters

Toxicity of Firebricks Used in Ovens

Trafficking in Glaze Recipes

Understanding Ceramic Materials

Understanding Ceramic Oxides

Understanding Glaze Slurry Properties

Understanding the Deflocculation Process in Slip Casting

Understanding the Terra Cotta Slip Casting Recipes In North America

Understanding Thermal Expansion in Ceramic Glazes

Unwanted Crystallization in a Cone 6 Glaze

Using Dextrin, Glycerine and CMC Gum together

Volcanic Ash

What Determines a Glaze's Firing Temperature?

What is a Mole, Checking Out the Mole

What is the Glaze Dragon?

Where do I start in understanding glazes?

Why Textbook Glazes Are So Difficult

Working with children

The Chemistry, Physics and Manufacturing of Glaze Frits

Description

A detailed discussion of the oxides and their purposes, crystallization, phase separation, thermal expansion, solubility, opacity, matteness, batching, melting. By Nilo Tozzi

Article

Glassy structure of frits

A glass is an inorganic product of melting that has been cooled to a solid state without crystallization. For normal glasses and frits, solidification to the amorphous state is effected by rapid raising of the viscosity of the melt during cooling. When the viscosity is high enough, elements are forced to assume an irregular three-dimensional network. This is true even for opaque and matt frits, the rapid quenching in water freezes the structure of molten batch.

Crystalline and vitreous silica molecular structure

Several things are needed for high silica glazes to crystallize as they cool. First a sufficiently fluid melt in which molecules can be mobile enough to assume their preferred connections. Second, cooling slowly enough to give them time to do this. Third, the slow cooling needs to occur at the temperature at which this best happens. Silica is highly crystallizable, melts of pure silica must be cooled very quickly to prevent crystallization. But Al2O3, and other oxides, disrupt the silicate hexagonal structure, making the glaze more resistant to crystallization.

Influence of modifiers on the structure

Frits cannot really be considered as glasses, rather, they are prevalently amorphous materials. In many cases the micro-matrix of the frit particles reveals that the identity of the original raw materials has not been lost, residuals of their crystal structure and relics of incompletely dissolved particles are evident (depending on melting conditions). Unlike glasses, where homogeneity is important in the melting and freezing process, for frits a homogeneous structure is of secondary importance. However, both frits and glasses have a disordered ultimate molecular structure, thus we can deduce that bonds between elemental atoms and oxygen have differing distances and strengths.

Due to bonds strength differences frits and glasses don’t have a definite melting point corresponding to a complete collapse of the entire structure. Rather a step-by-step breaking of bonds accompanies a gradual decrease in viscosity. The glassy structure described above suggests that chemical bonds among atoms must be partially covalent and partially ionic. This because covalent bonds have well defined angles and distances (incompatible with glassy structure) while ionic bonds are non-directional.

In order to understand the behavior of each element and its role in the glassy network we need to consider the differences in electro negativity among different elements and oxygen.

ELECTRO NEGATIVITY OF ELEMENTS IN OXIDE GLASSES| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boron | 2.0 | Berylium | 1.5 | Magnesium | 1.2 |

| Silicon | 1.8 | Aluminum | 1.5 | Calcium | 1.0 |

| Phosphorus | 2.1 | Titanium | 1.6 | Strontium | 1.0 |

| Arsenic | 2.0 | Zirconium | 1.6 | Barium | 0.9 |

| Antimony | 1.8 | Tin | 1.7 | Lithium | 1.0 |

| Sodium | 0.9 | ||||

| Potassium | 0.8 | ||||

Group 1: elements having higher electro-negativity, their oxides form glasses when melted alone.

Group 2: elements having oxides not able to form a glass when melted alone, but they will when melted with elements of group 1.

Group 3: elements never able to form a glassy structure.

While the quality of bonds and electro-negativity are good predictors of the behavior of elements in forming a glassy structure, there are other aspects not to be ignored. For instance the strength of the bonds and the number of electrons in the external shells of atoms (presenting the possibility of different coordination status) deserve consideration. In addition, oxides normally forming glasses can form crystalline structures if cooled too slowly, thus those prone to crystal formation can only be frozen to a glassy state if cooled more quickly. This kinetic aspect isn’t important for the frit-making process because the melts are quenched in water, however when frits are subjected to thermal treatment as glaze materials glass bonds can break and be rebuilt to crystal phases.

Crystallization reactions can partially evolve, depending on oxide ratios, to form crystals while excess components remain in as a glassy matrix. Considering electro-negativity, structural and kinetic approaches we have following table for main elements forming frits:

ELEMENTS OF GLASSES AND FRITS| Glass Makers | Intermediate | Modifiers |

|---|---|---|

| Si, Silicon | Al, Aluminum | Mg, Magnesium |

| B, Boron | Zr, Zirconium | Li, Lithium |

| Al, Aluminum | Ti, Titanium | Pb, Lead |

| Zr, Zirconium | Pb, Lead | Zn, Zinc |

| P, Phosphorus | Ba, Barium | |

| Ca, Calcium | ||

| Sr, Strontium | ||

| Na, Sodium | ||

| K, Potassium |

Silicate frits

Silica melts at 1710C and the glass melt is highly viscous, it is too refractory to be melted in a normal furnace. When we adjust the composition of a frit we are, in effect, modifying this hypothetic molten silica original glass by adding different elements in order to obtain suitable characteristics. Glassy silica is comprised of a network of tetrahedron SiO44- units and when we add modifiers or intermediate elements the continuous three-dimensional network is broken (and weakened) and the tetrahedrons connect to form different structures like chains, rings layers, etc.

The modifications we make to the original hypothetical silica glass structure (by adding different glass making, intermediate and modifier elements) enables us to control, among other things, the melting temperature and viscosity. Of course, frits and glazes must be available in a wide range of fusibilities in order to be used with different firing cycles. However, within each range we need to build glass bond networks having a range strengths in order to minimize variations of viscosity with temperature.

Silica Plus Modifier Matrix

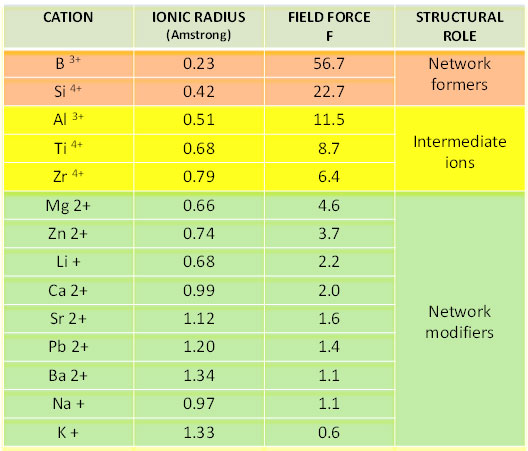

When we add intermediate or glass forming elements we have a more complicated evolution of glass (more detail later). The ionic field force F gives us an idea about how different ions participate in the formation of a glass network:

F = z/r2

Where z is the oxidation status of ion and r is its ionic radius.

For oxide glasses F is proportional to coordination power that each element exerts towards surrounding elements.

The ionic field forces F of the main frit elements are listed below:

Cations having high charges and small radiuses (and thus high field forces like boron and silicon), are network formers. Network modifiers have small charges, large radiuses and a big coordination number for oxygen ions. While considering ions as rigid spheres is an over-simplified way to describe reality, it has still proven useful to describe characteristics of each. For instance lithium has a ionic radius smaller than sodium and so it can locate into smaller cavities. The ionic field force of lithium is also stronger than sodium and it is essentially non-directional, thus it more easily produces crystals of a separate phase. Alkaline earth elements locate into cavities of the network as well, but they have double charges and thus act like a bridges between two oxygen ions (preventing the three-dimensional network from being fully destroyed). Moreover bonds between alkaline earth ions and oxygen are stronger than alkaline so we observe neither a rapid decrease in viscosity or a significant increase of the thermal expansion coefficient. It is notable that for similar molar percentages, frits containing magnesium crystallize more easily than frits containing calcium.

Aluminum, titanium and zirconium are classified as intermediate glass formers because they have a strong four-way coordination for oxygen ions, like silicon. Thus, for these oxides, we do not observe any interruption of the three-dimensional silicate-based network. For a better understanding consider more details about aluminum, boron, zirconium and titanium.

Aluminum: Usually aluminum shows a four-way coordination when it acts as a glass former, tetrahedrons are linked to four oxygen atoms while the local excess of negative charge is counterbalanced by an alkaline cation placed close to the aluminum ion. Thus additions of aluminum to a glass help to stop alkaline ions from breaking the three dimensional network of the glass. This produces the characteristic lower melt fluidity and tendency to crystallize and also reduces the thermal expansion and thermal stability. One downside to alumina is that it contributes to a higher viscosity of frit batches during melting (in the furnace tank) making homogenization more difficult. Usually the percentage of aluminum oxide is in the range 4 – 12%.

Boron: Boron is a basic component of frits yet its characteristics are so peculiar that it cannot easilly be compared to other elements. Boron, like aluminum, exhibits a four-way coordination when forming a glass network (being in the center of a tetrahedron of oxygen ions). This is possible only when the molar alkaline percentage is less than 30-40% because above this limit boron has three-way coordination, forming triangles.

Another peculiar characteristic is that boron is not just dispersed as tetrahedrons or triangles in the network of silica tetrahedrons. Rather it forms boric groups, containing from 3 to 5 boron atoms and the groups are randomly dispersed in the glassy matrix. However single BO3 triangles and BO4 tetrahedrons are always present. For quenched frits the presence of these groups is likely minimal but we can presume they form again when glazes containing the frit are fired (there are experimental evidences demonstrating this).

Boron oxide is an important component of low melting frits because it increases fusibility without a proportional increase in thermal expansion. Moreover boron oxide and sodium borate, due to their low melting point, are useful during smelting of frits because they form a glassy matrix early and act as catalysts in the melting and dissolving of other materials.

Zirconium - Titanium: Their influence on surrounding oxygen ions is very strong and scarcely directional so their solubility in frits is poor. Their solubility in glass and actions as glass formers are proportional to temperature. In quenched frits they remain in the dissolved in the glassy matrix but when we fire them again (within a glaze), these oxides easily precipitate crystal compounds.

Crystallization

It is the process leading to the formation of crystals from the disordered structure of a molten glass. As already discussed, we know that during the firing of a glaze the frit (or mixture of frits) can develop crystals like zircon, willemite or sphene giving opacity or characteristic surfaces. Generally speaking we can observe a crystallization when a liquid glass is saturated by an element forming a stable crystal.

We can visualize the firing process of a frit like this: Starting from room temperature the milled frit reaches a temperature at which ions acquire sufficient mobility to form crystals. These grow until the temperature is so high that the forming liquid glass becomes like a solvent and subsequently dissolves the crystals. However, during cooling we observe an opposite process, from a fixed temperature crystals appear again and grow until the melt viscosity is so high that ion mobility is zero. Of course the quantity and dimensions of crystals depends on the cooling cycle of the kiln and on the particle size distribution of frit grains (because nucleation of crystals starts from the surface of grains). In other words, surface aesthetic effects depend on firing and milling.

PHASES CRYSTALLIZING FROM FRITS

Crystals listed here precipitate from frits if the concentration of constituent elements is high enough and the firing conditions are sympathetic.

| PHASES CRYSTALLIZING FROM FRITS | |

|---|---|

| ANORTITE | CaO• Al2O3•2SiO2 |

| GEHLENITE | 2CaO• Al2O3• SiO2 |

| SPHENE | CaO• TiO2• SiO2 |

| WILLEMITE | 2ZnO• SiO2 |

| SPODUMENE | Li2O• Al2O3• 4SiO2 |

| WOLLASTINITE | CaO• SiO2 |

| RUTILE | TiO2 |

| FORSTERITE | 2MgO• SiO2 |

| ENSTATITE | MgO• SiO2 |

| DIOPSIDE | CaO• MgO• 2SiO2 |

| ZIRCONIUM SILICATE | Zr2•SiO2 |

| ZIRCONIUM OXIDE | ZrO2 |

| LEUCITE | K2O •Al2O3 •4SiO2 |

There are oxides and compounds that act as nucleating agents. For example, titanium oxide, tungsten oxide, tin oxide and calcium fluoride promote nucleus formation and enhance crystal development. When we speak about frits and glazes we have to consider that a glaze, even when composed of only one frit, is in contact with a ceramic body. This proximity implies that the glaze composition will change because there is a migration of elements from body to glaze and vice versa. This phenomena, could for example, be responsible for a matt glaze that fires fully transparent or slightly opalescent.

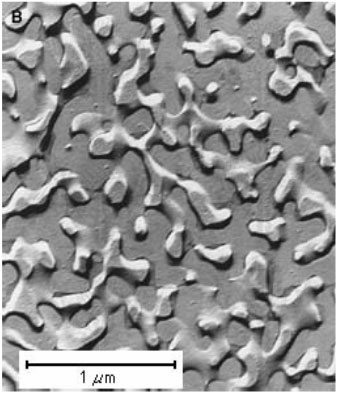

Phase separation

The effects of phase separation on the chemical and physical properties of glazes are not to be ignored, they can effect significant changes in thermal expansion, viscosity, and chemical resistance. Phase separation is an important characteristic of several glasses (for instance, the Vycor process is based on a phase separation to obtain pure silica glasses). In the case of ceramic frits we observe phase separation when they contain a large amounts of boron oxide and small amounts of alumina.

Phase Separation of a GlassTypes of Frits

The starting point from which to derive the composition of a frit suitable for our purposes is hypothetical silica glass.

Main criteria for normal frits are:

- Negligible solubility

- Thermal expansion lower than the ceramic body

- Fusibility suitable for firing cycle of corresponding glaze

- Wide soaking range

- Lowest possible cost of raw materials.

Consider the following theoretical process to create a transparent frit from silica:

- Add sodium and potassium oxides to enhance fusibility and lithium oxide, more expensive, just in case it is needed for special effects. For the same purpose we can also add small amounts of calcium, barium and zinc oxides keeping percentages under certain limits to avoid crystallization.

- At this point the original silica glass is more fusible but the resulting frit is similar to a window or bottle glass, perhaps it has some solubility and its viscosity changes a lot for small changes in temperature.

- We can limit the use of alkaline and alkaline earth oxides and adjust fusibility using boron oxide (it is a network former and we can keep solubility negligible using it).

- To reduce changes in melt viscosity with temperature and improve durability we add aluminum oxide (an added benefit is that aluminum oxide is sourced from low cost feldspars which can also supply alkaline oxides).

Oxide Effects on Physical Properties

Transparent Frits

So called “high temperature frits” are widely used for single firing and traditional frits are used for engobes or special glazes. I invented high temperature frits in 1982 based on two simple observations:

- Calcium and zinc matt glazes are defect free in the single firing process, even when fired at high temperatures

- A mixture 50/50 of these isn’t matt because the concentration of crystallizing elements is not enough to ensure crystal development during firing

- By increasing the alumina percentage we also avoid crystallization and the resulting frit is also more stable for higher temperatures.

The incentive for the initial research came from the necessity to prepare glossy glazes for single fired wall tiles, the so called “monoporosa” technology. In the process the frits crystallize on the surface forming a gas permeable layer of sintered grains (that survives to temperatures above 1000C). Under this the oxidation of organic matter in the body, the expulsion of crystallization water and the liberation of CO2 from carbonates can evolve without producing bubbles in glaze layer. Subsequent to this the glossy frits change from a solid form to a semi-solid one and then liquid with low viscosity within a narrow range of temperatures (for traditional frits viscosity changes take place over a broad range of temperature). These frits contain high percentages of calcium, magnesium, barium and zinc oxides so during pre-heating they also crystallize as alkaline earth compounds with silica and alumina. The cooling step in roller kilns is so fast that crystals cannot form again, thus the glazes appear glossy after firing.

Consider following glossy frit

| Oxide | Percentage |

|---|---|

| SiO2 | 61.5 |

| Al2O3 | 9 |

| B2O3 | 1 |

| BaO | 4 |

| CaO | 14 |

| MgO | 2 |

| ZnO | 5 |

| K2O | 2.5 |

| Na2O | 1 |

The percentage of zinc oxide is kept as low as possible for cost reasons. The calcium and magnesium oxides contribute to formation of crystals during pre-heating. Barium oxide enhances thermal expansion and brightness. The boron oxide percentage is small to keep the melting point high. The alumina keeps viscosity high at soaking temperature to avoid bubbling caused by over-firing and to avoid liquid phase separation.

Opaque Frits

Zirconium silicate is the best opacifier for frits in terms of cost and properties. It also has glass forming abilities as an intermediate element, it is a network former with coordination 4. Zirconium can remain in the glass network when the frit is quenched, but this status is not stable. During firing of the glaze the coordination changes to 6 as a modifier and afterwards to 7 as an oxide (which crystallizes). The first step towards opacity is precipitation of crystals of zirconium oxide and second by crystals of zirconium silicate, both are present in opaque glazes contributing to opacity. However a large amount of zircon remains in the glassy matrix, perhaps more than 50% and opacity is directly proportional to amount of zircon in the batch, usually more than 8%.

Matt Frits

Once quenched in water frits are amorphous and transparent but sometimes, during firing of the host glaze, we obtain a matt surface texture. We observe a crystallization process leading to the formation of one or more crystal phases as a consequence of thermal treatment. We obtain a matt frit when the composition is suitable but the quantity, shape and dimensions of the crystals depend on the thermal treatment of the glaze. Recently it has been customary to describe as ceramic-glass some glazes or grains of frit that have been strongly crystallized after firing. But, it is also evident that traditional matt glazes can be considered as ceramic-glasses. The biggest difference between traditional and more recent products is composition (recent products borrow their composition from true ceramic-glasses which are densely crystallized). In order to overcome problems of simple calcium or zinc matt frits (high expansion for calcium – cost and poor acid resistance for zinc) we prefer frits crystallizing different a phase (like anortite, spodumene, zircon or wollastonite).

Matt Frit Example

| Oxide | Percentage |

|---|---|

| SiO2 | 51.0 |

| Al2O3 | 1 |

| B2O3 | 5 |

| CaO | 37 |

| MgO | 1 |

| ZnO | 4.6 |

| K2O | 0.2 |

| Na2O | 0.2 |

During firing the above frit crystallizes wollastonite and its thermal expansion is about 76 x 10-7 C-1.

Frit Production

Fritting is the process to produce a non-soluble and glassy product, starting from a batch composed of natural raw materials and chemicals, and quenching the melt in water in order to produce a crumbled and brittle glass. The process is triggered by low melting compounds (like boric acid, borax, alkaline carbonates, feldspars) and subsequently accelerated by them to melting and dissolve the more refractory materials like quartz sand, zircon flour, aluminium oxide, etc. Frits play an essential role in obtaining glassy glazes at normal firing temperature of ceramic tiles.

Usually we describe frits by oxide composition, like glasses. But this method is not fully correct because a glass is absolutely homogeneous while a frit can be non-homogeneous (and thus characteristics can change depending on homogeneity status). For example, we can easily imagine a frit containing some undissolved quartz as being more fusible than a similar one that is completely homogeneous. Frits usually have a higher viscosity than glasses and so it is not as easy get a completely amorphous and homogeneous product (even at maximum running temperatures of tank furnaces and melting times). Materials like zircon or silica sand slowly dissolve and often we have relics of these materials in the quenched frit. During firing of the host glaze we can observe crystallization or liquid phase separation and the extension of these reactions strictly depends on the homogeneity of the frit itself. However we use oxide composition to describe a frit because it is a fast method and it also enables us to calculate characteristics like thermal expansion, surface tension, molar composition and Seger formula. However, to give a complete picture of frit it is a habit provide characteristic temperatures (using a heating microscope apparatus) and measured thermal expansion (or a calculated one).

Behavior of specific materials during the melting process

Alkali carbonates: They melt at respective melting points and quickly enter the glassy matrix lowering the viscosity.

Barium carbonate/Calcium carbonate/Dolomite: They loose carbon dioxide at respective temperatures and quickly react entering the glassy matrix.

Boric acid: Above 180C it loses crystallization water and oxide B2O3 melts at 300C. Due to its low melting point boric oxide is the first material forming a liquid phase in tank furnace.

Borax: Above 120C it loses crystallization water and it melts at 740C.

Colemanite: It is a natural raw material having formula 2CaO •3B2O3 •5H2O and a content of boron oxide in the range 36–42%. It has a violent reaction during water elimination at 400C and melts around 1100C.

Feldspar: At normal running temperatures of tank furnaces they quickly melt forming a viscous glass.

Silica sand: It slowly dissolves in the melt when its viscosity decreases enough to enhance migration speed of silicon ions through the glassy network. Usually we have a good speed when temperature is 200–300C above the melting temperature of the frit (viscosity is low and migration speed of ions is good enough).

Zirconium silicate: We use milled zirconium silicate having average size of grains 25 microns (grains of original zircon sand are too big for a rapid dissolving of material in the liquid frit). Zircon starts to melt at 1380C forming a liquid phase and zirconium oxide, but its solubility in the liquid phase is poor and dissolving time quite long. Often it settles to the bottom of tank furnaces forming a deposit of zirconium silicate and zirconium oxide.

Batching and melting

Batching is fully automatic: each material is extracted from its silo and weighed by a hopper, where all components are added. The batch is transferred to a mixer and then to a pneumatic conveyor transferring it to the silo feeding the tank furnace. Of course the procedure is controlled by a computer where all compositions are stored (it also records number of prepared batches for each tank furnace). The batch is transferred to the tank furnace by a cochlea or piston according to a fixed speed. This speed regulates the melting or staying time of the frit in tank furnace. Pressure and temperature in the tank furnace are controlled. The depth of the molten frit depends on tank furnace design. Frit is expelled from the exit hole and falls into the water.

Quality Control

The main control is made by preparing and firing a tile glazed with the new frit and comparing it to one made with same thickness of the standard material. In case the frit is opaque we often add to each glaze a fixed amount of cobalt oxide in order to compare opacity. A further important control is executed by preparing a small cylinder of powdered frit, as shown in the picture, and firing it. We can then compare fusibility and opacity with a similar cylinder prepared from the standard frit. If more tight control is needed we can compare the characteristic temperatures derived from a heating microscope with similar data from the standard frit.

Related Information

A frit softens over a wide temperature range

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Raw materials often have a specific melting temperature (or they melt quickly over a narrow temperature range). We can use the GLFL test to demonstrate the development of melt fluidity between a frit and a raw material. On the left we see five flows of boron Ferro Frit 3195, across 200 degrees F. Its melting pattern is slow and continuous: It starts flowing at 1550F (although it began to turn to a glass at 1500F) and is falling off the bottom of the runway by 1750F. The Gerstley Borate (GB), on the other hand, goes from no melting at 1600F to flowing off the bottom by 1625F! But GB has a complex melting pattern, there is more to its story. Notice the flow at 1625F is not transparent, that is because the Ulexite mineral within GB has melted but its Colemanite has not. Later, at 1700F, the Colemanite melts and the glass becomes transparent. Technicians call this melting behaviour "phase transition", that does not happen with the frit.

A bad batch of frit - Glaze manufacturers must deal with this

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Just as Mother Nature is responsible for variations in natural minerals, commercial frit manufacturers can and do release material with variations. Frits are made of recipes that must be dosed, mixed, smelted, quenched and ground - leaving plenty of room for error in the process. Shown here is an example of a combination of improper mixing and inadequate smelting. Frits can be made from soluble and carbonate materials that off-gas during smelting, leaving a glass of zero LOI. But that did not happen here: This melt fluidity test comparing two batches of the same frit shows a good and faulty one. The volatiles (as exhibited by the bubbles) were not the only problem, a glaze containing 50% of this had severely inadequate melting. Interestingly, the two-pallet batch (according to the marking on the bags) showed the best results at the top of the first pallet and the worst at the bottom of the second. Another load of faulty frit received later showed similar bubbling but was alumina-short (turning our production matte glaze glossy).

Links

| Glossary |

Melting Temperature

The melting temperature of ceramic glazes is a product of many complex factors. The manner of melting can be a slow softening or a sudden liquifying. |

| Glossary |

Frit

Frits are used in ceramic glazes for a wide range of reasons. They are man-made glass powders of controlled chemistry with many advantages over raw materials. |

| Glossary |

Fast Fire Glazes

Industrial ceramics are fired very quickly and require minimal micro bubbles and zero pinholes and blisters. Fast fire late melting glazes accomplish that. |

| Tests |

Heating Microscope Analysis

|

| Tests |

Frit Fusibility Test

|

| Projects |

Frits

|

By Nilo Tozzi

Got a Question?

Buy me a coffee and we can talk

https://digitalfire.com, All Rights Reserved

Privacy Policy