| Monthly Tech-Tip | No tracking! No ads! |

A Low Cost Tester of Glaze Melt Fluidity

A One-speed Lab or Studio Slurry Mixer

A Textbook Cone 6 Matte Glaze With Problems

Adjusting Glaze Expansion by Calculation to Solve Shivering

Alberta Slip, 20 Years of Substitution for Albany Slip

An Overview of Ceramic Stains

Are You in Control of Your Production Process?

Are Your Glazes Food Safe or are They Leachable?

Attack on Glass: Corrosion Attack Mechanisms

Ball Milling Glazes, Bodies, Engobes

Binders for Ceramic Bodies

Bringing Out the Big Guns in Craze Control: MgO (G1215U)

Can We Help You Fix a Specific Problem?

Ceramic Glazes Today

Ceramic Material Nomenclature

Ceramic Tile Clay Body Formulation

Changing Our View of Glazes

Chemistry vs. Matrix Blending to Create Glazes from Native Materials

Concentrate on One Good Glaze

Copper Red Glazes

Crazing and Bacteria: Is There a Hazard?

Crazing in Stoneware Glazes: Treating the Causes, Not the Symptoms

Creating a Non-Glaze Ceramic Slip or Engobe

Creating Your Own Budget Glaze

Crystal Glazes: Understanding the Process and Materials

Deflocculants: A Detailed Overview

Demonstrating Glaze Fit Issues to Students

Diagnosing a Casting Problem at a Sanitaryware Plant

Drying Ceramics Without Cracks

Duplicating Albany Slip

Duplicating AP Green Fireclay

Electric Hobby Kilns: What You Need to Know

Fighting the Glaze Dragon

Firing Clay Test Bars

Firing: What Happens to Ceramic Ware in a Firing Kiln

First You See It Then You Don't: Raku Glaze Stability

Fixing a glaze that does not stay in suspension

Formulating a body using clays native to your area

Formulating a Clear Glaze Compatible with Chrome-Tin Stains

Formulating a Porcelain

Formulating Ash and Native-Material Glazes

G1214M Cone 5-7 20x5 glossy transparent glaze

G1214W Cone 6 transparent glaze

G1214Z Cone 6 matte glaze

G1916M Cone 06-04 transparent glaze

Getting the Glaze Color You Want: Working With Stains

Glaze and Body Pigments and Stains in the Ceramic Tile Industry

Glaze Chemistry Basics - Formula, Analysis, Mole%, Unity

Glaze chemistry using a frit of approximate analysis

Glaze Recipes: Formulate and Make Your Own Instead

Having Your Glaze Tested for Toxic Metal Release

High Gloss Glazes

Hire Us for a 3D Printing Project

How a Material Chemical Analysis is Done

How desktop INSIGHT Deals With Unity, LOI and Formula Weight

How to Find and Test Your Own Native Clays

I have always done it this way!

Inkjet Decoration of Ceramic Tiles

Is Your Fired Ware Safe?

Leaching Cone 6 Glaze Case Study

Limit Formulas and Target Formulas

Low Budget Testing of Ceramic Glazes

Make Your Own Ball Mill Stand

Making Glaze Testing Cones

Monoporosa or Single Fired Wall Tiles

Organic Matter in Clays: Detailed Overview

Outdoor Weather Resistant Ceramics

Painting Glazes Rather Than Dipping or Spraying

Particle Size Distribution of Ceramic Powders

Porcelain Tile, Vitrified Tile

Rationalizing Conflicting Opinions About Plasticity

Ravenscrag Slip is Born

Recylcing Scrap Clay

Reducing the Firing Temperature of a Glaze From Cone 10 to 6

Setting up a Clay Testing Program in Your Company

Simple Physical Testing of Clays

Single Fire Glazing

Soluble Salts in Minerals: Detailed Overview

Some Keys to Dealing With Firing Cracks

Stoneware Casting Body Recipes

Substituting Cornwall Stone

Super-Refined Terra Sigillata

The Chemistry, Physics and Manufacturing of Glaze Frits

The Effect of Glaze Fit on Fired Ware Strength

The Four Levels on Which to View Ceramic Glazes

The Majolica Earthenware Process

The Potter's Prayer

The Right Chemistry for a Cone 6 MgO Matte

The Trials of Being the Only Technical Person in the Club

The Whining Stops Here: A Realistic Look at Clay Bodies

Those Unlabelled Bags and Buckets

Tiles and Mosaics for Potters

Toxicity of Firebricks Used in Ovens

Trafficking in Glaze Recipes

Understanding Ceramic Materials

Understanding Ceramic Oxides

Understanding Glaze Slurry Properties

Understanding the Deflocculation Process in Slip Casting

Understanding the Terra Cotta Slip Casting Recipes In North America

Understanding Thermal Expansion in Ceramic Glazes

Unwanted Crystallization in a Cone 6 Glaze

Using Dextrin, Glycerine and CMC Gum together

Volcanic Ash

What Determines a Glaze's Firing Temperature?

What is a Mole, Checking Out the Mole

What is the Glaze Dragon?

Where do I start in understanding glazes?

Why Textbook Glazes Are So Difficult

Working with children

Glaze Types, Formulation and Application in the Tile Industry

Description

An technical overview of various glaze type used in the tile industry along with consideration of the materials, processes and firing. By Nilo Tozzi

Article

We can outline an exhaustive set of relationships between the firing and fired characteristics of frits and pigments and their oxide compositions but we cannot do this it for glazes. For glazes, reactions and processes developing during firing never reach a steady state of equilibrium. Thus glazes, after firing, can be considered anything from glasses having a local random distribution of elements (where phases have a more orderly arrangement of elements) to absolutely dispersed crystalline phases.

Consider a simple hypothetical glaze containing 50% frit and 50% natural or synthetic crystalline materials: After firing this glaze will show specific characteristics that we can only partially foresee. We need a more "scientific" approach that will give us a better level of control and the ability to foresee the aesthetic result after firing, we need a lot of information.

For instance:

- For each frit or mixture: the composition, the homogeneity status, the particle size distribution or specific surface area.

- For each natural or synthetic crystalline material: the composition and structure, the crystalline phase and their progressions with temperature and interrelationships (for non homogeneous materials), particle size distribution or specific surface area.

- Thickness of glaze before firing.

- Composition of ceramic body and, by extension, the interface reactions between glaze and ceramic body.

- Actual curve of temperature vs. time in which the glaze will be fired, in other words, the calories imposed on the glaze at each instant of the temperature curve.

- Composition of the kiln atmosphere.

Having all of the above information we can begin to visualize the progression of each solid state reaction and the chemical composition of each amorphous and crystalline phase after firing. Still, it is difficult to get a picture close to the real final physical fired product. The number of surprises coming out of the kiln and the number of variables involved quickly make it evident that glazes and their materials are very complicated. Thus I like to imagine a glaze as being like a match: we have to strike a match to see if it works like we have to test a glaze to see its surface.

Firing Reactions

It is not possible to go into a lot details about workings and kinetics of reactions and transformations because these, in complex glazes, are many and interrelated and can interfere with each other in difficult-to-predict ways.

For instance, there is no use speculating about the transformation of kaolin into mullite if the host glaze is composed of a large percentage of frit and a small amount of kaolin because the latter is just going dissolve into the frit melt before its transformation. However this transformation is important to consider for engobes where a large amount of kaolin and a small amount of frit are present. This is because kaolin dissolves partially and the remaining larger amount contributes to opacity because it transforms into mullite crystals. Another example is barium carbonate: it experiences its decomposition reaction at 1450C (which is higher than similar ones for calcium and magnesium carbonates). But this is irrelevant because in glazes it reacts at lower temperatures with other materials and easily dissolves into glassy matrix (it is impossible to foresee when barium carbonate will start decomposition). A further example is the melting process for feldspars or nepheline: it goes on at lower temperatures because of being accelerated by molten frits or alkaline earth compounds (otherwise feldspar and nepheline contribute to developing a viscous glaze that can impede other reactions). The possible compositions are infinite and it is not practical to attempt to examine all different interactions or lack thereof. We can only outline what happens.

| Heating | Cooling | |

|---|---|---|

| Transformations in a Single Phase | Processes Between Two Different Phases | Crystallization |

| Water elimination from hydrous materials | Coagulation of melting grains of frits | Separation of liquid phases |

| CO2 elimination from carbonates | Incorporating of crystal phase by molten frits | |

| Polymorphic transformations | Reactions among crystalline materials and formation of new phases | |

| Structural reorganizations | Partial or total dissolving of crystalline materials in the molten frits | |

| New phases forming | Homogenization of molten frits having different composition | |

| Melting | ||

For several processes we are in the presence of solid state reactions where the equilibrium state is slowly reached or never reached and where specific surface area of particles plays a very important role.

Glaze Types

In order to simplify the issue I will describe some glazes having specific intrinsic characteristics which have been developed to obtain some aesthetic result.

Engobes

Engobes have an intermediate composition between bodies and glazes. Their purpose is to hide the color of the ceramic body and eliminate reactions and associated defects caused by the direct contact between glaze and body.

All engobes have 2 primary characteristics (compared to glazes):

- High content of plastic materials like clays and kaolins.

- High opacity and high content of crystalline materials.

The plastic materials in the engobe absorb water in the overlying glaze in a slow and uniform way (without discontinuities in water absorption). Thus quality and quantity of clays in an engobe play a very important role. For single fired tiles we usually have percentages in the 15-30 range (depending on the plasticity of each clay). Together with plastic clays we can also use less plastic kaolins to regulate water absorption and contribute to opacity. Frits, if present, are opaque and feldspars or nepheline are always present in order to impart fusibility using low cost materials.

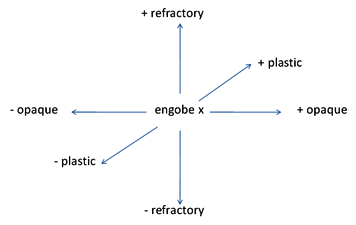

Changes in Hypothetical Engobe

For instance, consider the following engobe composition as a example of the kind of changes we need for a specific production process.

| Engobe X | ||

|---|---|---|

| Clay | 25 | |

| Kaolin | 25 | |

| Nepheline Syenite | 50 | |

| Composition Changes for Engobe X | |

|---|---|

| +refractory | Partially replace nepheline with quartz and alumina |

| -refractory | Partially replace kaolin with an opaque frit |

| +opaque | Partially replace kaolin with a micronized zircon |

| -opaque | Partially replace kaolin with nepheline |

| +plastic | Partially replace kaolin with clay |

| -plastic | Partially replace clay with kaolin |

Glossy Glazes (transparent and opaque)

Glossy transparent and opaque glazes are prepared from high temperature frits with small additions of kaolin, clay, nepheline, feldspar and zirconium silicate.

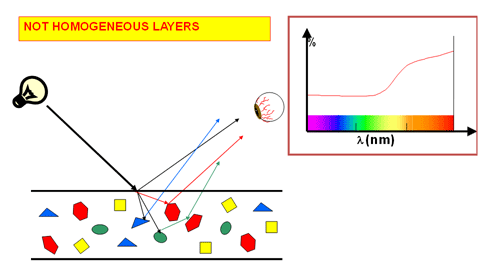

First, consider opacity: Opacity can be attained by different mechanisms:

- Using frits containing zirconium or other elements promoting crystal formation during firing

- Employing crystalline compounds directly

- Promoting phase separations in the glassy matrix in order to obtain two or more glasses having different refraction indexes.

The coating ability of an opaque glaze is expressed by reflectance, expressed as a ratio of the intensity of back-diffused light and intensity of incident light or by percentage of reflectance compared with the reflectance of a standard material.

Variables having a mayor impact on the back-diffused light are:

- Refraction index of opacifier

- Thickness of glaze layer

- Number of particles of opacifier

- Shape and particle size distribution of opacifiers

The following figure displays a reflectance measurement from an opaque red glaze.

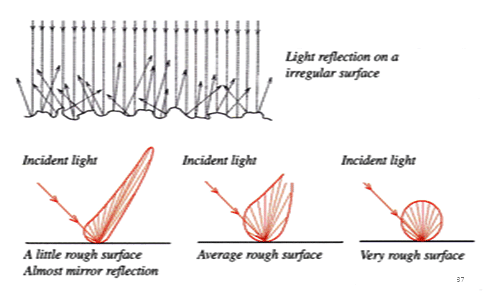

Matt Glazes

A glaze is matt when crystalline materials are dispersed in the glassy matrix. the quantity and dimensions of the crystals for each added crystalline material control the surface texture (varying from semi-glossy to very rough). The resultant irregular surface of the glaze, where crystals are dispersed, causes reflection of incident light in all directions.

To obtain a glassy layer containing dispersed crystals able to modify the surface we can employ the mechanisms of:

- Crystalline compounds separating from frits during firing

- Crystalline compounds added that are stable enough to overcome firing without totally dissolving in the glassy matrix.

To get the best control of dispersed crystal quantities we simultaneously use matt frits and crystalline compounds. Despite this matt glazes are strongly affected by firing cycle, thickness of glaze layer and particle size after milling. Likewise the temperature and the firing cycle are very important because they shape crystallization from frits and dissolving kinetics of added crystals.

During firing we have the formation of an intermediate layer between glaze and engobe, this layer prevents crystallization of frits because it contains a greater amount of aluminum migrating from the engobe (alumina impedes crystallization).

Particle size after milling of different added crystalline materials also affects their quantity and stability because smaller crystals more easily dissolve in the glassy matrix.

Actually, all materials having high melting temperatures are helpful in obtaining matt surfaces. Most used are corundum, alumina, quartz, mullite, wollastonite, rutile, etc. Sometimes, in cases where we want to obtain a rustic surface, we also add materials having large grain dimensions ( e.g. sands of quartz, rutile, zircon and corundum).

The Effects of Various Materials

Alumina/Corundum: Alumina is a white powder or aggregate of corundum crystals and it can be added to glazes before and after milling. If it is added before milling aggregates are destroyed and the alumina is more reactive (in cases of solid state reactions with other components of the glaze). If it is added after milling it acts like a refractory material, not dissolving into the glass, imparting unique qualities to the surface (depending on its particle size distribution).

| Alumina Oxide - Corundum | |

|---|---|

| Chemical Formula | Al2O3 |

| Melting Temperature | 2045C |

| Refraction Index | 1.7 |

| Specific Gravity | 3.5-3.9 |

| Mohs Hardness | 9 |

Due to it superior hardness, alumina is also used to improve abrasion resistance of glazes. Small amounts of alumina are also employed to control crystallization, surface texture and chemical resistance, while larger amounts, as already noted, remain partially undissolved and contribute to hardness and opacity (even if its refraction index is not suitable). Of course the glaze becomes matt with a texture depending on the amount of alumina. Excess alumina causes a microscopic porosity of the glaze layer according to the degree to which it becomes more refractory.

Corundum single crystal particles are less brittle and less reactive than alumina and they are employed primarily to produce hard surfaces. However its particle size distribution before and after milling are important because melt fluidity of glazes during firing is strongly affected by its surface area.

Barium carbonate/Calcium carbonate/Magnesium carbonate/Dolomite: All of these compounds decompose in glazes generating reactive oxides that easily dissolve in the melt. If percentages are limited, usually less than 10%, they contribute to fusibility and glossiness. But for higher percentages they contribute to crystal development during cooling and glazes start becoming matt. Of course regarding the development of matt surfaces for these materials, we have to consider the molecular weight of each. For instance, magnesium crystallizes more readily than barium because, in terms of moles, 1% barium equals 4% magnesium.

Clay: The main use of clays is to prepare engobes, usually they are a mixture of illite, kaolin and quartz. The criteria to select a good clay are:

- High content of illite or plastic materials like kaolin or ball clays

- Low content of iron or titanium oxides (which yellow the color).

The so called "ball clays" are actually made up of fine particled kaolin and organic matter, both imparting some degree of plasticity.

Kaolin: It is a component of all glazes, primarily for its suspending properties. A good glaze kaolin must be white after firing and plastic. Its transformation to mullite above 1000C is important because, in case it does not dissolve in the glassy matrix, it transforms and makes a small contribution to opacity (having refraction index = 1.64).

Nepheline: The most popular nepheline minerals are Canadian and Norwegian. They are a mixture of albite, microcline (potassium feldspar) and nepheline. In glazes nepheline melts at a lower temperature than feldspars, around 1100C, and contributes to forming a transparent and viscous glassy phase. Additionally, nepheline has a lower iron and titanium content than feldspars.

| Nepheline Syenite | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxide | Canadian | Norwegian | Theoretical |

| SiO2 | 60.0 | 56.0 | 41.1 |

| Al2O3 | 23.2 | 24.2 | 34.9 |

| Fe2O3 | 0.10 | 0.11 | |

| CaO | 0.25 | 1.2 | |

| Na2O | 10.8 | 7.8 | 15.9 |

| K2O | 5.1 | 9.1 | 8.1 |

| LOI | 0.5 | 1.5 | |

Quartz: Quartz is the most common structural form of silica. While it undergoes several structural transformations that are of concern for body formulation these have little importance when we use quartz to prepare glazes (because the alfa/beta changes are reversible and the quartz/tridymite transformation is very slow). Quartz dissolves slowly in glazes at a rate proportional to the fluidity of the glassy phase and inversely proportional to it particle size. When quartz dissolves into the melt it imparts more viscosity, if it does not dissolve it partially contributes to opacity and gives a less glossy surface.

| Structural Changes of Silica | |

|---|---|

| Alfa Quartz/Beta Quartz | 575C |

| Alfa Cristobalite/Beta Cristobalite | 220-275C |

| Alfa Tridymite/Beta Tridymite | 117C |

| Quartz/Tridymite | >870C |

| Tridymite/Cristobalite | 1460-1480C |

| Quartz/Cristobalite | 1400-1600C |

Quartz has a specific use when we prepare engobes: we need a high thermal expansion to counterbalance body or glaze behavior. In such cases it is not unusual to add more than 30% quartz (its high expansion before transformation at 575C is particularly beneficial).

Sodium/potassium feldspar: Feldspars have a wide range of compositions but we also find feldspar in other minerals and often with quartz. Pure sodium feldspar (albite) quickly melts at 1150C and produces a glass while potassium feldspar melts at around 1200C producing a more a viscous melt (and a crystalline phase named leucite that contributes to opacity). Sodium feldspars are more suitable for mattes while we prefer potassium feldspar for glossy glazes.

Titanium oxide: Anatase is a not stable phase of titanium at the firing temperatures of glazes, it transforms to rutile or dissolves into the glassy matrix and re-crystallizes during cooling (with rutile structure) or acts as a crystallization catalyst.

| Titanium Oxide | ||

|---|---|---|

| Anatase | Rutile | |

| Chemical Formula | TiO2 | TiO2 |

| Melting Temperature | 1855C | 1830C |

| Mohs Hardness | 5.8 | 6-6.5 |

| Refraction Index | 2.5 | 2.76 |

Wollastonite: It exhibits a very slight solubility in water but slips containing wollastonite have an alkaline pH of 9-11, this can influence rheological properties even for small percentage additions. During firing, if percentages are less than 10, it easily dissolves in glazes giving more fusibility and more glossiness. For larger amounts it remains partially undissolved or crystallizes again during cooling, contributing to the development of matt surfaces. Likewise, as can be seen from observing fired characteristics, high wollastonite glazes often have a poor hardness and some tendency to craze.

| Wollastonite | ||

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Formula | CaSiO3 | |

| Melting Temperature | 1540C | |

| Thermal Expansion | 65 x 10-7 C-1 | |

| Refraction Index | 1.63 | |

| Mohs Hardness | 4.5-5 | |

| Solubility in Water | 95 mg/l | |

Zinc oxide: While it has high melting point it easily dissolves in glaze melts giving more fluidity (if less than 10% is present). For higher percentages it can produce crystal phases like Zn2SiO4 (willemite).

The oxygen-zinc bond has a prevalent covalent character and so it is network modifier having a limited effect on thermal expansion. Unfortunately zinc is expensive and glazes containing it are acid leachable. Also, sometimes, for specific zinc oxides and for specific percentages, glaze slips can become tixotropic because during milling the surface of the oxide particles forms a hydroxide layer. For this reason it normal to prepare glazes having matt texture using frits containing high percentages of zinc oxide.

Zirconium silicate: Its decomposition in glass matrix is slight and slow. It strongly contributes to opacity because its refractive index is high (particularly when we use micronized zircon, having a particle size less than 5 microns). Zircon sand is used for rustic glazes and zircon flour for semi- transparent glazes. Its specific gravity is high and slips or glazes containing zircon thus have high density.

| Zirconium Silicate | ||

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Formula | ZrSiO4 | |

| Melting Temperature | Above 1600C decomposes to zirconium and silicon oxides | |

| Thermal Expansion | 72 x 10-7 C-1 | |

| Refraction Index | 1.9-2.0 | |

| Specific Gravity | 4.6-4.7 | |

| Mohs Hardness | 7-7.5 | |

Glaze Application

We already well know all the problems of traditional application devices like bell, disc, aerograph, printing machines (dry and wet), etc. However I would like to focus attention on a couple fairly new techniques and one not so popular.Tintometric Systems

Actually automatic equipment to prepare printing pastes are not a recent innovation, they are in in every day use. Tiles are characterized by decoration and there are a large number of printing machines in glazing lines, however management of inks is often difficult. A Tintometric system is able to prepare a colored ink on the basis of a colorimetric measurement in the lab and using a limited number of pigments. The main characteristics of tintometric systems are:

- Reduction of pigment use to 10-15%

- Optimization of ink quantities for glazing line (on the basis of square meters produced)

- Total recovery of tailings

- Consistent production time after time using the same ink

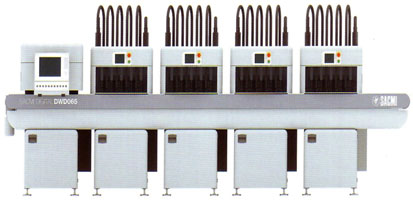

Inkjet Decoration

The application of colors by the inkjet system, without contact between printer an tile and with high resolution, opens many new prospects for tiles decoration. Ink jet technology is of course widely used for paper printers but it is quite new and still under development for tiles. While the cost of inks and equipment are high the method guarantees great flexibility (much of the potential is still to be explored.

The new machines use inks quite similar to those traditionally used for glaze line printing machines. Some are using a four-color process while others work using all available pigments (thus without color limitations) and also using dry powders.

Related Information

Links

| Articles |

Ceramic Tile Clay Body Formulation

An overview of the technical challenges a technician in the tile industry faces in making good tiles from the least expensive materials and process possible. |

| Articles |

Porcelain Tile, Vitrified Tile

A technical overview of the bodies, firing, processes and types of porcelain tiles against the backdrop of the historical development of the process since the 1970s. |

| Articles |

Monoporosa or Single Fired Wall Tiles

A history, technical description of the process and body and glaze materials overview of the monoporosa single fire glazed wall tile process from the man who invented it. |

| Articles |

Glaze and Body Pigments and Stains in the Ceramic Tile Industry

A complete discussion of how ceramic pigments and stains are manufactured and used in the tile industry. It includes theory, types, colors, opacification, processing, particles size, testing information. |

| Articles |

Inkjet Decoration of Ceramic Tiles

Theory and description of various ceramic ink and inkjet printing technologies for ceramic tile, the issues technicians and factories face, inket printer product overview. |

| Projects |

Frits

|

| Glossary |

Ceramic Slip

The term Slip can have various meanings in traditional ceramics. |

| Glossary |

Ceramic Tile

Tile manufacture is the largest sector of ceramic industry. Engineers overcome the very difficult technical challenges of drying and firing defect-free, flat and durable tile. Potters can do it too. |

By Nilo Tozzi

Got a Question?

Buy me a coffee and we can talk

https://digitalfire.com, All Rights Reserved

Privacy Policy