| Monthly Tech-Tip | Feb 14-15, 2026 - Major Server Upgrade Done | No tracking! No ads! |

Glaze Chemistry

Case studies where glaze chemistry was used to solve a problem.

Related Information

A high feldspar glaze is settling, running and crazing. What to do?

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

The original cone 6 recipe, WCB, fires to a beautiful brilliant deep blue green (shown in column 2 of this Insight-live screen-shot). But it is crazing and settling badly in the bucket. The crazing is because of high KNaO (potassium and sodium from the high feldspar). The settling is because there is almost no clay in the recipe. Adjustment 1 (column 3 in the picture) eliminates the feldspar and sources Al2O3 from kaolin and KNaO from Frit 3110 (preserving the glaze's chemistry). To make that happen the amounts of other materials had to be juggled. But the fired test revealed that this one, although very similar, is melting more (because the frit releases its oxides more readily than feldspar). Adjustment 2 (column 4) proposes a 10-part silica addition. SiO2 is the glass former, the more a glaze will accept without losing the intended visual character, the better. The result is less running and more durability and resistance to leaching.

Is the N505 cone 6 matte glaze recipe what you think it is?

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

This recipe is from page 2 of the booklet: "15 Tried & True Cone 6 Glaze Recipes". Click the following code, G3955, to see more information on how it compares with G2934 and G1214Z1 mattes. This flow test and these test tiles were in the same kiln, fired at cone 6 using our PLC6DS schedule. The defining characteristic of N505 is its extreme melt fluidity - it runs because it is overtired at cone 6. Still, the surface on the tile (lower right) is arguably more interesting than G2934. Some felt pen marking reveals why: The micro surface is much rougher. To its credit, although it does stain easier, it can still be cleaned with effort.

From the chemistry, shown on Insight-Live side-by-side screenshot. It has very low Al2O3 and SiO2 - that turns on some red and yellow lights. One could hope to have melt fluidity and great functionality, but they pretty well never go together. This glaze should fire glossy - the 6% magnesium carbonate is the mechanism of the matteness - MagCarb is super refractory, it may not be dissolving in the. melt. The glaze should cutlery mark (although it seemed hard in our testing). Most important, low Si:Al levels always carry the risk of leaching - exercise caution adding any significant percentage of heavy metal pigments. Crazing is another possible issue over melted glaze.

Sourcing Li2O from spodumene instead of lithium carbonate comes at a cost

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Lithium carbonate is now ultra-expensive. Yet the reactive glaze on the left needs it. Spodumene has a high enough Li2O concentration to be a possible source here. It also has a complex chemistry, but the other oxides it contains are those common to glazes anyway. Using my account at insight-live.com, I did the calculations and got a pretty good match in the formulas (lower section in the green boxes). Then I made 10-gram balls and did a GLFL test at 2200F (notice the long crystals in the glass pools below the runways). Not surprisingly, this recipe is very runny, that's why the tiny yellow crystals grow during cooling. The new version fires very similar, perhaps better. Our calculated cost to mix this recipe in 2022 was $17.84/kg vs. $10.40/kg. But there is a practical cost: Poor slurry properties. The spodumene sources so much Al2O3 that 70% Alberta Slip had to be dropped to accommodate it! How does one use this type of glaze without ruining kiln shelves? Using a catcher glaze is one answer.

High feldspar glazes craze. Don't put up with it.

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

This glaze, "Bamboo Cone 10%", contains 50% potash feldspar so or certainly qualified as a high feldspar glaze. K2O and Na2O are this over supplied. They have the highest thermal expansions of all oxides, by far. These are needed and valuable - but when grossly over supplied the result is crazing. This glaze used to work on this body, H550. The previous version of H550 was firing near the bloating point of the body, about 1% porosity, so the recipe had to be changed to provide more margin for error. The new recipe has a more practical 2.0-2.5% porosity, it has no danger of bloating or warping and still has excellent maturity and strength. This glaze was crazing before and pieces did not leak because the body was dense enough - so they were still water tight. But now it does not work. The solution is to do something that should have been done before: Use a silky matte base recipe that does not craze. We recommend our G2571A base (below right) - the Zircopax, rutile and iron oxide in the original can be added to it instead.

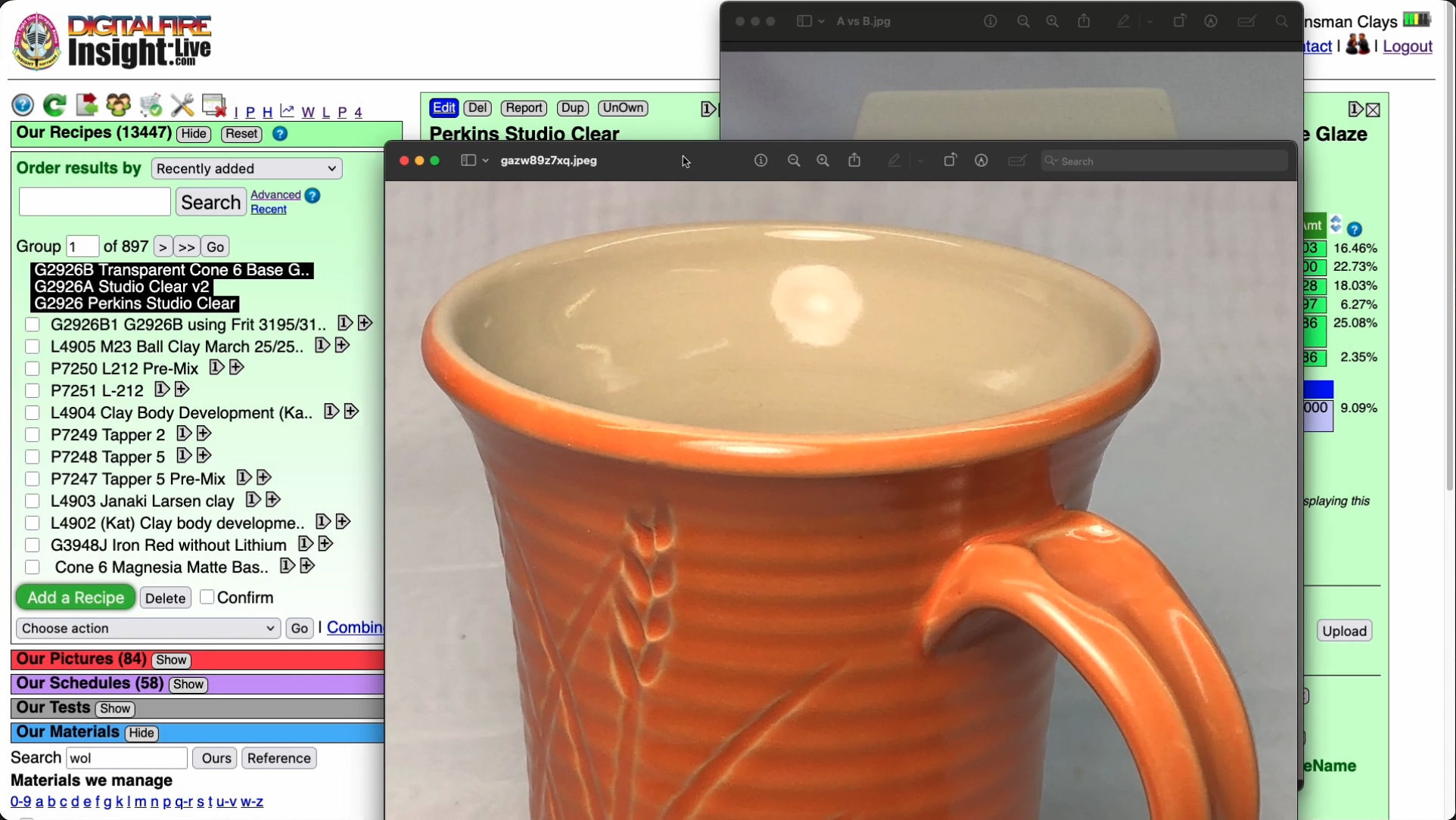

How I calculated a feldspar-to-frit replacement in a cone 10R clear glaze

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

A screen shot of side-by-side panels in my account at Insight-live.com. On the left is the original G1947U recipe. On the right I have substituted frit 3110 as a higher-concentration-source of KNaO. This enabled actually increasing KNaO to get a better gloss and melt. I have introduced calcined kaolin (to ratio with the raw kaolin to control slurry and drying properties). I added frit 3249 to introduce low-expansion MgO to counterbalance the higher levels of KNaO. That frit, like the 3110, will not only melt things better simply because it itself was pre-melted, but it also brings along a little boron. That supercharges melting and enables an enhancement: The addition of more SiO2. The low thermal expansions of MgO, SiO2 and B2O3 counterbalance the increase that will occur as a result of the higher KNaO (0.15-0.26). Sound boring? When you see the unexpected results you might think differently (see the linked post below). I never considered using frits at cone 10R before, this success led to an improvement in my main silky matte glaze also.

Sanity checking a cone 6 purple pottery glaze

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

A customer was having serious trouble with this cone 6 glaze recipe shivering. A quick check of its chemistry reveals the reason: It has the lowest calculated thermal expansion we have ever seen! The reason is the high spodumene and talc levels. Adding the 3% cobalt also makes this among the most expensive we have seen. To say this recipe looks non-typical is an understatement. And, it raises flags on working properties and susceptibility to leaching in both limit recipes (e.g. very low clay content, high talc and spodumene) and limit formulas (stratospheric levels of Li2O and MgO coupled with plenty of cobalt).

The hard panning problem can be fixed easily: Supply the same amount of Li2O from lithium carbonate (only 10% is needed so the overall recipe cost is reduced), which makes room in the recipe for clay (to supply the lost Al2O3 and SiO2 from the spodumene). Second, introduce KNaO at the expense of MgO and Li2O, which will greatly increase the thermal expansion and reduce or stop the shivering.

Use a frit blend ratio to control the amount of kaolin in a glaze recipe

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

These are the recipes and calculated oxide chemistries of two pottery glazes (as shown in my account at insight-live.com): The original problem recipe and an adjustment to fix it. Recipe #1 sources boron from a soluble material and three plastic materials are combined to increase drying shrinkage enough to cause cracking when drying (and thus crawling). Recipe #2 solves these problems while producing the same chemistry. It sources boron from two frits (one having almost no Al2O3) whose ratio to each other can be altered to supply more or less Al2O3 to the melt. That enables removing two of the plastics: Ball clay and Gerstley Borate. The remaining 20% EPK is perfect to create a creamy slurry that suspends, applies and dries well.

Imagine realizing that pottery you're selling is all going to craze!

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

What if every single piece you have been making is all eventually going to craze? Do you refund all the customers? All because you trusted a liner glaze recipe found online. At a reputable site. This recipe is called "Classic White". And it has "classic crazing". On going back to the source web page you find there is no mention of even the possibility of crazing. Then you type the recipe into your account at Insight-live.com and are horrified to see how high the thermal expansion calculates to (see red circles on picture). Then you realize that, based on simple recipe limits, you could have steered clear of this just by looking at it. Then you find there are other well-documented base glossy and matte recipes that do not craze (like G2934 and G2926B). Even if they do they are adjustable to enable fixing the issue. And you can even blend them to create any degree of satin desired. And they use a mix of tin oxide and Zircopax to avoid crawling. And they are durable, don't cutlery mark, don't leach, don't run, don't settle in the bucket.

Substitute Ferro Frit 3134, using glaze chemistry, in three glaze types

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Can't get frit 3134 for glaze recipes? Can you replace it with frit 3124? No, 3124 has five times the amount of Al2O3 (the second most important oxide in glazes) and half the amount of B2O3 (the main melter). This ten-minute video presents a glaze chemistry approach that is easier to do than you probably think. It deals with three different glaze recipe types lacking sufficient clay to suspend the slurry. Learn to source the needed oxides from two other Ferro frits, 3110 (or Fusion F-75) and 3195 (Fusion F-2), and end up with at least 15% kaolin in each. A unique approach is required in each situation. Two of the calculations produce improved slurry properties and one yields a recipe of significantly lower cost. If you have a recipe that needs this and need help please contact us.

The recipe reveals why a pottery glaze is peeling when multi-layered

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Dipping glazes can, in very controlled circumstances, be multi-layered. If you have done it for some time, with success, you may have been just lucky. These pieces demonstrate one of many factors that can produce failure: The top glaze contains 7% bentonite and 5% zinc oxide - that is 12% hyper-fine particles, perfect to create the drying shrinkage to make this happen. The recipe author must have reasoned that it could "pinch hit" for the inadequate clay content. But 7% bentonite in any glaze is highly unusual. And, it is actually not even necessary here. Why? The high percentage of Ferro Frit 3124 is sourcing needless Al2O3 (alumina), that should be coming from kaolin or ball clay instead. Frit 3134 is the perfect stand-in, it contains almost no Al2O3, but otherwise is quite similar. The equivalent recipe we calculated on the right has the same chemistry, but does pass a sanity check. It is not guaranteed to work, but has a better chance than this one. For even more assurance of success, it should be mixed as a base-coat dipping glaze.

What to do about lithium carbonate and Gerstley Borate in glazes

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Lithium is getting really expensive. These are four recipes submitted by a customer who wonders if there is a substitute. The answer is not simple, each glaze is a unique situation. Fortunately, lithium carbonate is almost always a minor addition (in the first two recipes it is 1% and 3%). Lithium is a powerful low expansion flux, in some cases, a low melting low expansion frit could perform the same function (e.g. Ferro 3249). Even for the 6.5%, as in the third one, this could still work. But in these cases wouldn't it be better to continue using lithium? Even for the last one that has 9%? It's only expensive if you make glazes and don't use them. Perhaps a solution is to make them as brushing glazes, a 1-pint jar only needs about 350g of powder (that is only about 30g for recipe 4).

This situation can also be considered as an opportunity to rationalize the recipes you use. Let's pretend that each of these might be used on functional ware and should measure up to common sense recipe limits. The Gerstley Borate in three of these is also a red flag, that won't be available shortly (calculating how to source B2O3 from frits is better anyway). During that process, you might find that lithium is not even needed. Another issue is thermal expansion. Notice that one of these calculates to 8.5 and another to 9.6! Those are virtually certain to craze. Why not lower that number while removing the Gerstley Borate? Notice that two of these have clay percentages over 70% (Alberta Slip and Gerstley Borate), these are virtually certain to crack on drying (and crawl on firing), that can also be fixed. The percentage of titanium, Zircopax and rutile in the fourth one are guaranteed to make it crystallize heavily on cooling produce problems with cutlery marking and staining.

From Scribbles to Success: Fixing This Glaze Recipe

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

If you do DIY pottery glazing you may have recipes scribbled onto cards like this. But the card is not the big issue here, it is that recipe! It really needs some work. Here is what could be done.

-Add this as a recipe in an account at insight-live.com (and assign it a code number) to start a testing project. Along the way document it with pictures, firing schedules, general notes, etc.

-With all that feldspar it is sure to craze, reducing the high thermal expansion K2O it contributes in favor of low expansion MgO (from talc) is the most likely fix.

-With all that clay (29 total) it is likely to crack while drying (and then crawl during firing), split it into part calcined kaolin and part raw kaolin (the ball clay is not needed).

-And those colorants: It is better to use cobalt oxide than carbonate. Perhaps the burnt umber could be increased to eliminate the need for both the manganese and iron (since it supplies both and has zero LOI). Better yet, remove all four and use a black stain (7% would likely be enough).

Calculating the highest % of 3B clay to create a glaze recipe

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

In this screenshot I am comparing the chemistries of two recipes. The recipes are different but the chemistries are the same. On the left, Plainsman 3B (also known as MNP) is being using to source almost all of the Al2O3 (the red box) needed by the recipe (to match our standard cone 10R transparent G1947U, on the right). The KNaO is being sourced from the frit rather than feldspar (this is really good because it has almost no Al2O3 so all of it can be sourced from the 3B clay). Only silica and calcium carbonate are needed to bring the SiO2 and CaO up to match.

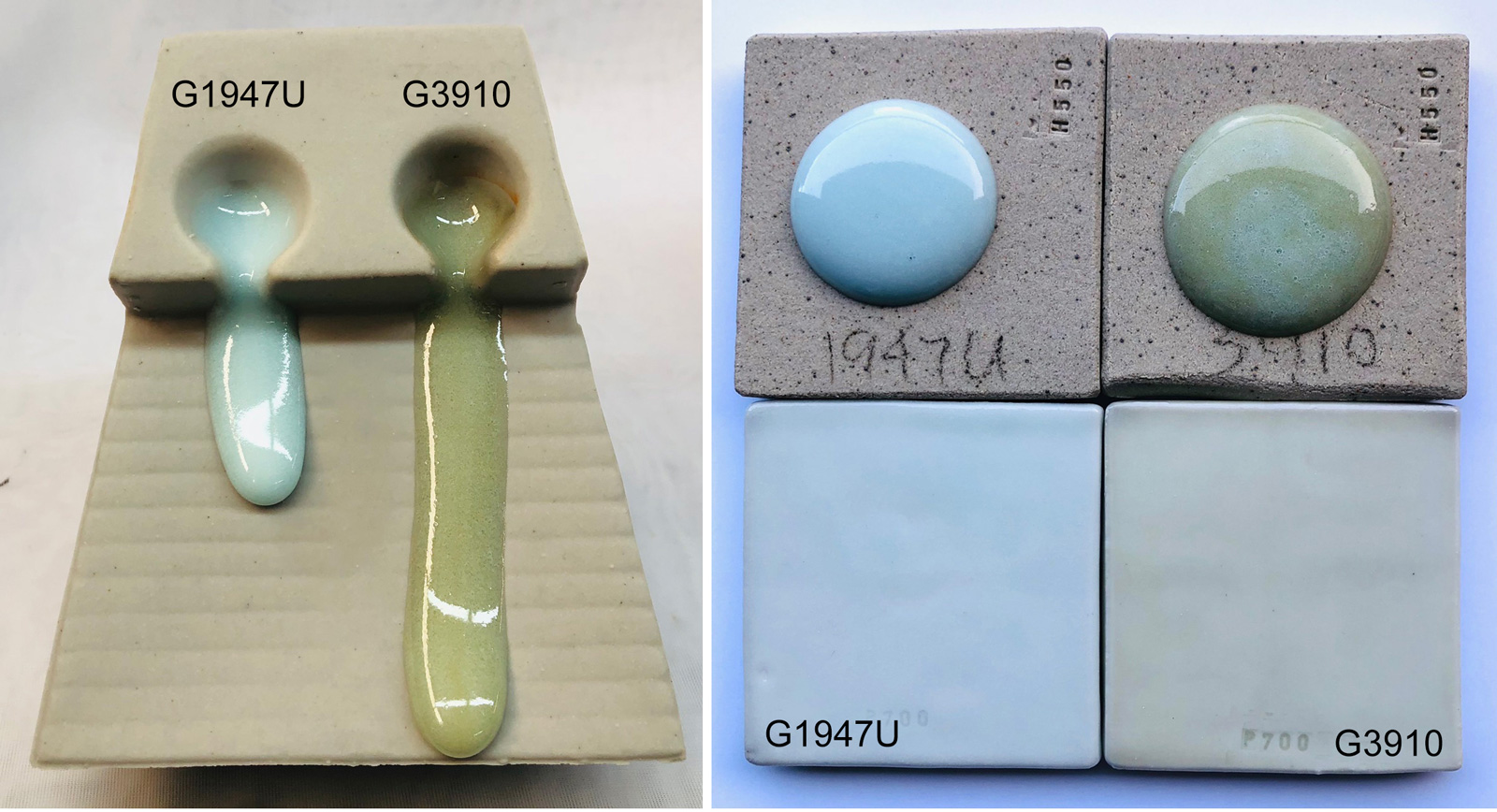

Use a frit instead of feldspar in a cone 10 glaze.

A good reason to do that.

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Using my account at Insight-live.com I calculated a frit-based recipe having an "evolved" chemistry from the original G1947U feldspar-based one. Only after seeing the fired results did I fully realize I made a discovery as well as an improvement. My original approach was just theoretical: Shift KNaO-sourcing from feldspar to frit to get a better melt (just because the frit is a premelted source of KNaO). As calculations took shape it became clear that I could increase KNaO (it is a super-flux for cone 10 brilliant surfaces) because of the multiple options to counterbalance its high thermal expansion. Those options would theoretically supercharge melting more, that gave me confidence the melt could even dissolve additional SiO2 (which would improve durability). When the kiln opened I got the surprise with the original G1947U: It never looked white before! But when seeing it this thick in comparison to the improved version, it looks really cloudy. Why? Likely the melt is not completely dissolving the particles of quartz! The "lead glaze surface brilliance" of the new G3910 blew me away at first, but now that I realize it is also melting all the silica I see how much better it potentially is. One issue: The transparency of G3910 brings with it the amber color of the body:glaze interface.

Links

Video |

How I Developed the G2926B Cone 6 Transparent Base Glaze

How I found a pottery glaze recipe on Facebook, substituted a frit for the Gerstley Borate (using glaze chemistry), compared using a melt flow tester, added as much extra SiO2 as it would tolerate, and got a durable and easy-to-use cone 6 clear. |

Video |

Converting G1214M Cone 6 transparent glaze to G1214Z matte

How I converted a glossy glaze into a matte glaze by using glaze chemistry and recipe logic. |

Got a Question?

Buy me a coffee and we can talk

https://digitalfire.com, All Rights Reserved

Privacy Policy