| Monthly Tech-Tip | Feb 14-15, 2026 - Major Server Upgrade Done | No tracking! No ads! |

Crawling

Ask yourself the right questions to figure out the real cause of a glaze crawling issue. Deal with the problem, not the symptoms.

Details

Crawling is where the molten glaze withdraws into 'islands' leaving bare clay patches. The edges of the islands are thickened and smoothly rounded. This is among the most costly problems in ceramic production, ware requires refiring and is often lost anyway. In moderate cases there are only a few bare patches, in severe cases the glaze forms beads and even drips off onto the shelf. The problem is prevalent where dipping glazes are applied to bisque, shrink on drying and form cracks. This is usually because the glaze has excessive plastic clay content or is applied too thickly.

It is common to see this issue misdiagnosed on social media - someone submits a picture and among the dozens of comments no one asks about the recipe or mentions the factors noted below.

Is the glaze shrinking too much during drying?

If the dried glaze forms a network of cracks it is a sign that the glaze is shrinking too much or its bond with the body is poor. The fault lines provide places for the crawling to start (especially where the island cracks delineate raised edges that are no longer in contact with the body). There are a number of possible contributors:

- It is normal to see 20% clays (ball clay, kaolin). If significantly more is present try using a less plastic clay (i.e. kaolin instead of ball clay, low plasticity kaolin instead of high plasticity kaolin, or a mix of calcined and raw kaolin). Ultimately you must tune the glaze recipe's clay content to achieve a compromise of good hardness and minimal shrinkage while maintaining the chemistry (Want to learn how? Please email).

- If a slurry has flocculated (due to changes in water, dry material additions like iron oxide, or addition of an acid, epsom salts, calcium chloride, etc) it will require more water to achieve the same flow and will therefore shrink more during drying and require a longer period to dry. Try using distilled water. Always measure the specific gravity to maintain solids content and use deflocculants/flocculants if necessary to thin/thicken the slurry (remove water from an existing glaze slurry by pouring some on a plaster batt, then mixing the water-reduced mass back in).

- Gerstley Borate is plastic and therefore contributes to glaze shrinkage, especially if the recipe also contains kaolin or ball clay. It also tends to gel glazes so they need excessive water. Use boron frits instead. Try a boron frit (do calculations to make these adjustments, there is no frit that has the same chemistry).

- Many potters add bentonite to every glaze they make, thinking that it will help suspend. But when glazes already have sufficient, or even excessive clay content, the extra bentonite may increase the shrinkage enough to cause drying cracks.

- If very fine-particled materials are present (i.e. zinc, bone ash, light magnesium carbonate) these will contribute to higher shrinkage during drying. Try using calcined zinc, synthetic bone ash or another source of calcia, talc or dolomite to source magnesia instead of magnesium carbonate. If a glaze has been ball milled for too long it may shrink excessively (for example, zircon opacified glazes can be ground more finely than tin ones). Highly ground glazes may produce a fluffy lay down.

- Again, be "recipe flexible", tune the raw clay content. Use enough clay in the glaze mix to both suspend the slurry and toughen the dried layer, more than that risks excessive shrinkage. Less and the glaze does not harden and forms a powdery surface. A fool-proof way to reduce shrinkage is to calcine (see the link below) part of the clay. If there is 35% kaolin in the mix, then try using 15% calcined kaolin and 20% raw kaolin (calcine the clay yourself if needed, it is easy). If there is 70% Alberta Slip, try using 35% raw and 35% calcined. Adjust the proportion as you get experience in working with the glaze. One detail: If there is significant clay content, adjust for the LOI (weight lost during firing) when calcining. Kaolin, for example, loses 12% weight on firing, so use 12% less calcined). Alberta Slip and Ravenscrag Slip have 9% LOI.

It is possible to create glaze slurries that gel and flow extremely well, dry hard and do not crack by using the right kaolin (i.e. EPK) or ball clay (i.e. Old Hickory #5, No. 5 Glaze) in adequate amounts. It is very important to realize that many ball clays and kaolins to not produce glazes of good slurry properties (without additives), a simple substitution can make a remarkable difference. It may not seem that glaze chemistry is related to this subject of getting the right type and right amount of clay in a recipe. But it very much is. Why? Because the ability to juggle a recipe to source Al2O3 from a clay or a feldspar/frit, as needed, enables controlling the amount of clay in the recipe while maintaining its fired character. Chemistry also gives you the ability to switch between different types of clay (that have different oxide makeups).

Is the glaze's dry-bond with the ware surface inadequate?

The mechanism of the bond between dry glaze and body is simply one of physical contact, the roughness of the ware surface copmbined with the ability of the liquid glaze to flow into all the tiny surface pores and irregularities and the degree to which it is able to dry hard without shrinking too much, these determine its ability to 'hang on'.

- Some surfaces can seem very smooth (e.g. slip cast surfaces), but microscopically they are not. Still, the glaze needs enough fluidity to flow onto and wet the surface well.

- If the dried glaze surface is excessively powdery incorporate more plastic clay (chemistry will be needed to juggle the recipe). Or add a little bentonite. If there is 10% kaolin, for example, consider changing that to 7% kaolin and 3% bentonite (there is a chemistry impact here, but not significant).

- Adding gum to a glaze will harden it and bond it better to bisque, this often solves crawling problems. Beware that excessive gum can increase drying time and dripping considerably, so do test to achieve a compromise.

- If a glaze is flocculated it may lack the necessary fluidity to run into tiny surface irregularities in the bisque and establish a firm foothold. However, some degree of flocculation is valuable, it enables the glaze to set and gel quickly after dipping, this can really accelerate production.

- Wetting agents are available and can be added to the slurry to improve bond. But again, do not substitute these for the basics, the right amount of clay and degree of fluidity.

Does application technique or handling compromise the fragile glaze-body bond?

- If ware is heavily dusted consider blowing it off. But a little dust is not an issue (remember glaze itself is 100% dust).

- If glaze is applied too thickly the forces imposed by its shrinkage will overcome its ability to maintain a bond with the ware surface (especially inside corners or at sudden discontinuities). If a glaze can be applied more thinly, do so.

- Use a fountain glazing machine to do the insides of bowls and containers to achieve a thinner layer.

- If glaze needs to be applied in a thick layer, you can achieve a lower water content by deflocculating the glaze (i.e. with some sodium silicate or Darvan). Use caution with this, it may then tend to dry very slowly or form drips that crack and peel and instigate crawling. It is better to just have the right clay content.

- When applying the glaze in the normal layer thickness be careful to prevent drips that form thicker sections that can crack away during drying. It is practical to 'gel' the glaze slightly (i.e. with vinegar, Epsom salts) so that it 'stays put' after dipping or pouring.

- If a double-layer of glaze needs to be applied be careful that the second does not shrink excessively and pull at the first, compromising its bond with the body. If possible, the upper layer should have less clay, lower shrinkage, should be applied thinner and dry quickly. It may be necessary to bisque each layer on before applying the next. Double-layering typical raw art and pottery glazes is difficult, special consideration must be given. Have you successfully done this in the past without any special attention? You may have simply been very lucky.

- When doing double-layer glazing be careful that the second layer is not flocculated (with an associated high water content). This will rewet the first layer and loosen it from the body. Adding iron oxide, for example, to a glaze will often flocculate it and require the addition of much more water to restore the same fluidity.

- Spraying glaze on in such a way that the glaze-body bond is repeatedly dried and rewetted could a produce shrinkage-expansion cycle that compromises a glaze-bisque bond that could otherwise withstand one drying-shrink cycle.

- Force-drying of the ware can make the glaze visibly crack when it otherwise would not (slower shrinkage associated with slower drying gives it the glaze time to ease body interface tension by micro cracking). Preheating the bisque too much may cause escaping steam to rupture the bond with the ware.

- Rough handling of ware can compromise sections of the glaze body bond.

- For the inside of slip cast ware, consider pouring a thin glaze slurry into the mold of a just-drained piece (perhaps a minute or two after the mold has been drained) and immediately pouring it out again. This base layer can be fired on in the bisque.

Is the glaze drying too slow?

- This often occurs where ware is very thin (e.g. slipcasting or fine porcelain), the bisque is fired to higher density, glaze has a high water content or ware is already wet from a previous glazing (or a combination of these factors). If the glaze dries too slowly the most fragile stages of the adhesion mechanism are extended and cracks or bubbles develop. These low-bond areas instigate crawling during melting. To fix this problem speed up drying. You can do this by preheating the bisque (in a kiln to 150C or more if necessary) before dipping, doing separate interior and exterior glazing (with a drying period in between), applying glaze in a thinner layer, reducing glaze water content, bisquing lower to increase porosity or increasing wall thickness in the ware.

Is the ware once-fire?

- Once-fired ware is prone to crawling because the mechanical glaze-body bond is more difficult to achieve and maintain. If glaze is applied to leather hard ware it must shrink with the body. During the early stages of firing the ware also goes through volume changes and chemical changes that generate gases, these affect the ability of the glaze to hang on.

- When glaze is applied to leather hard ware you must be able to tune its shrinkage by adjusting the amounts and nature of the clays in the recipe while maintaining the overall chemistry (calculations may be needed).

- In damp conditions the powdery layer may reabsorb water from the air causing slight expansion of the glaze layer, thereby affecting the adhesion.

Is the problem happening during firing?

- If glaze is applied over stains or oxides that lack flux (e.g. chrome pinks, manganese types, greens, cobalt aluminate) it can be prevented from bonding well with the underlying body. Mix under-glaze stains with a flux medium so that over lying glazes can 'wet' them and form a glassy bond.

- If the glazed ware is put into the kiln wet and therefore dried quickly during the early stages of firing, the glaze layer will tend to crack and curl and crawling can occur.

- If glazed ware is put into a kiln containing heavy damp ware such that early stages of firing occur in very high humidity conditions the glaze could be rewetted and forced through an expansion-shrinkage cycle (that could affect its bond with the body).

- If a glaze contains significant organic materials (i.e. gums, binders) that gas off excessively during firing the bond may be affected. Decomposition of materials like whiting can also generate significant amounts of gas within the glaze layer (try switching to wollastonite, it has no LOI and supplies SiO2 and will permit reducing the silica content accordingly).

- Raw zinc oxide is very fine and tends to pull a glaze together during firing, use calcined zinc instead (most zincs sold to potters are calcined).

- If the glaze contains significant zircon opacifier, alumina, some stains, magnesium carbonate, the melt may be much 'stiffer' and flow less. This can affect its ability to resist crawling.

- Watch out for glazes with slightly soluble materials like Gerstley Borate or wood ash. With the former the soluble portion tends to be the borate, which will be absorbed into the bisque during application. Then, during firing, it creates a highly fluid layer between the body and the less developed over glaze, it thereby prevents adhesion of the glaze to the body. Use frit to source boron instead. In addition soluble materials tend to flocculate (thicken) the slurry and attempts to thin them result in higher water content and therefore increased shrinkage.

- If the bisque firing is reduced or not adequately oxidized and excessive gases are generated during certain stages of the glaze firing, these can affect the glaze-body bond.

- The chemistry of glaze may be such that the surface tension of the melt encourages crawling (e.g. high alumina, high tin, significant chrome/manganese colorants, lack of fluxes of low surface tension).

Is there a problem with the body?

- If the clay body contains soluble salts that come to the surface during drying, these can affect the fired melt's ability to form a glassy bond with the body. Precipitate these salts with a small body addition of barium carbonate (for information on how this works search for Barium Carbonate in the materials section).

- As noted above, if the body surface is too smooth, the glaze may not be able to adhere properly.

Is this problem inherent in the type of glaze being used?

Matte glazes are more prone to crawling. Why? Because they usually have high Al2O3. The major contributor of that oxide is clay, especially kaolin. Matte glazes commonly have 35% kaolin in the recipe. Use part calcined material, part raw kaolin to deal with this problem.

Many pottery glazes have high feldspar and low clay contents, simply because they were improperly formulated. Using chemistry, you can shift the recipe to supply part of the Al2O3 from kaolin instead of the feldspar, reducing the feldspar percentage (this involves corrections in the amount of silica and other materials also).

Slip glazes can have 70, 80 or even 90% of a slip clay in them. Alberta Slip and Ravenscrag slip are examples. These materials melt by themselves to make glazes. But they are clays, they shrink. Follow the instructions from the manufacturer on how to use them properly.

Related Information

Crawling glazes withdraw into islands during melting

The cause is almost always obvious upon seeing the recipe

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

This problem is almost always caused by glazes shrinking too much during drying and then cracking. Those cracks become the crawl points during firing. Excessive shrinkage is normally a product of too much raw clay in a glaze. Even glazes a marginally high clay can crack if applied too thickly. It is likewise with multi-layer application done without consideration for the specific needs of that process (e.g. failure to use a base coat glaze for the first layer). Multi-layering of glazes rewets the first layer, stressing its bond with the body and pulling it away from the body as it shrinks. Base coat glazes have better adherence. Crawling is quite prevalent in once-fired ware since glaze bonding is more tenuous.

To state again: Glazes contain clay to suspend their slurries. Clay shrinks when it dries. Some shrinkage can be tolerated but when it is excessive, something has to give. As glaze layer thickness increases, it is afforded more and more power to impose its shrinkage on the bond with the body. At some point, that bond will be compromised in places where cracks occur to release the tension. Even if these do not appear on dry ware, bond compromise can still exist.

ChatGPT is surprisingly wrong about the causes of glaze crawling.

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

ChatGPT trained on the entire internet and yet gave 100% wrong answers and neglected the key thing that causes 90% of crawling! How can the internet be so wrong? Consider the suggestions it gave:

-Dust or oil on the bisque: This almost never happens. Besides, glaze is a mix of dust and water!

-Too much feldspar in a glaze can cause it to shrink excessively during firing: No, high feldspar causes thermal expansion/contraction of the fired glass, not physical shrinkage of the melt.

-If the clay body surface is not roughened, the glaze may not adhere properly: No, glazes don’t crawl any more on porcelains than other bodies.

-If the glaze is too thick in some areas and too thin in others, it can crawl in the thin areas: No, it crawls where thick because that’s where it cracks during drying.

-Over-firing or under-firing: No. Glazes fired to the ideal temperature crawl just as much.

-If the pottery is dried evenly or the drying process is too rapid: No, rapid drying of glaze on bisque is important to prevent cracking.

This crawling happened because the glaze cracked along the inside of that corner during drying. Such cracking is by far the number one cause of crawling, the melt pulls back from either side of the crack. The specific gravity of the slurry was too high, the resulting greater thickness right at the corner gave the shrinking glaze power to pull a crack. Adding water to bring the SG back down to 1.4 and then Epsom salts to gel it to thixotropic gave the slurry much better dipping and drying properties and totally solved this issue.

Clay in a glaze recipes. Why is it there?

What happens when there is too much?

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

If I put this on social, I might get 100 comments on the cause. Most would say it's applied too thick. That is not correct. At the top, it is too thick, but not at the bottom (where it is still cracking). Crawling during firing is almost certain.

Before offering any opinion, one needs to sanity check the recipe. This one, GA6-B, contains a lot of clay. Why do dipping glazes contain clay, usually kaolin, ball clay? To suspend the slurry, slow down drying, gel the slurry to make it thixotropic and harden the layer on drying. But their chemistry is also important, clays supply the all-important Al2O3 and SiO2 to the melt (which would otherwise have to come from feldspar). Certain clays excel at suspending. 15-20% EP kaolin, for example, is all that is needed. It’s not that plastic, but sticky and thixotropic (Grolleg and New Zealand kaolins are similar or even better). 10% of a gelling ball clay might be enough. However, 50% of a silty non-plastic clay might be needed. When the clay has too much influence, glazes shrink too much as they dry and then crack like this. Ones lacking clay (or employing one that is not suitable) have poor application properties (for dipping) and are powdery. This glaze has 80% pure raw Alberta Slip. That is a plastic clay, no wonder this is happening! 50% of it needs to be roasted.

Crawling on a thickly applied glaze (cone 6)

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Example of glaze crawling on the inside of a stoneware mug. Notice how thick it is. Thickly applied glazes have more ability to assert their shrinkage during drying and thus compromise their bond with the body below. The cracks that appear become bare patches after firing.

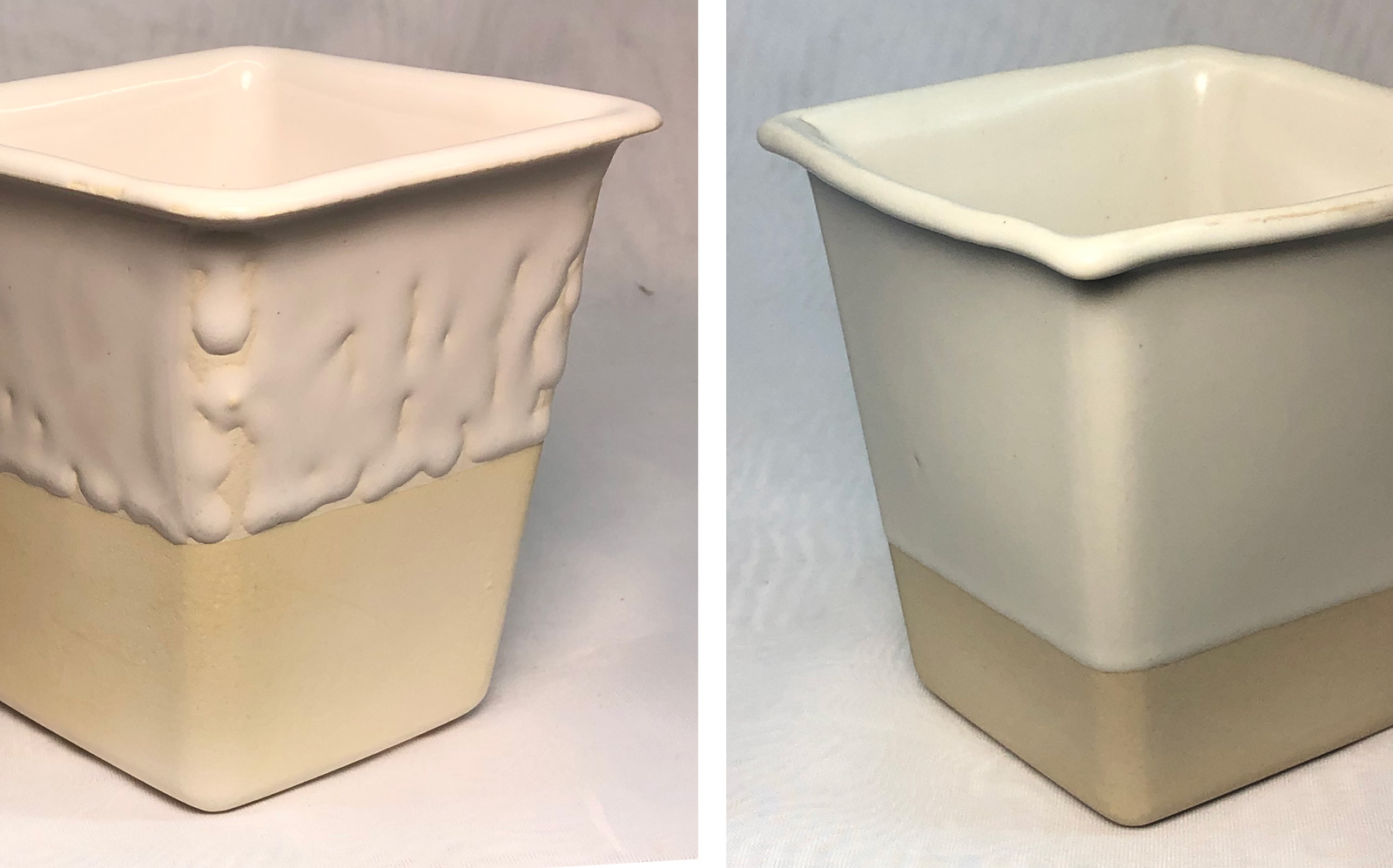

Two glazes. One crawls, the other does not. Why?

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

The glaze on the right is crawling at the inside corner. Why? Multiple factors contribute. The angle between the wall and base is sharper. A thicker layer of glaze has collected there (the thicker it is the more power it has to impose a crack as it shrinks during drying). It also shrinks more during drying because it has a higher water content. But the leading cause: Its high raw clay content increases drying shrinkage. Calcining part of the raw clay destroys its affinity for water (which is what makes it plastic), this is an effective way to deal with this. Or doing a little chemistry to source some of the Al2O3 from materials other than clay (e.g. a frit having a higher Al2O3 content).

Majolica glaze crawling on this slip-cast terra cotta

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Mitigating factors are poor adherence of the glaze to the smooth-surfaced L4170B terra cotta bisque, high zircon content in the glaze (it reduces melt fluidity) and the very thick application (this is a variation on G1916Q as a majolica glaze). Which is the most important of those factors? The adherence to the bisque. An addition of Veegum CER solved the problem (50g of the solution to 0.75 litres of glaze slurry, with added water to thin it out). Unlike with CMC gum, this slurry still goes on thick and evenly. Although the piece on the left is darker red, that is a photo issue, these were both the same body and fired at cone 04.

Crawling can happen when paint-on glazes are layered over dipping glazes

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

This bowl was dipped in a non-gummed clear dipping glaze. Such glazes are optimized for fast drying and even coverage. However their bond with the bisque is fragile. The blue over-glaze was applied thickly on the rim (so it would run downward during firing). But during drying, it shrunk and pulled the base coat away at the rim (likely forming many tiny cracks at the interface between the clear and the bisque. That initiated the cascade of crawling. When gummed dipping glazes are going to be painted over, a base-coat dipping glaze should be used. What is that? It is simply a regular fast-dry dipping glaze with some CMC gum added (perhaps half the amount as what would be used for painting). There is a cost to this: Longer drying times after dipping and less even coverage. And gum destroys the ability to gel the glaze and make the slurry thixotropic.

Crawling in G2934Y Zircopax white glaze: Here are some fixes.

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

G2934Y, a variation of the G2934 base, is a good stain matte base glaze but it is not without issues. It has significant clay content in the recipe and high levels of Al2O3 in the chemistry, these make it susceptible to crawling. This base is normally fine as is but when opacified or certain stains are added (especially at significant percentages) it can crawl. This has 10% Zircopax. Even though the glaze layer thickens at the recess of the handle join it is still crawling. We also get this on the insides of mugs where wall and foot meet at a sharp angle. This was initiated because the glaze cracked here during drying. Normally it would heal but the zircon stiffens the melt, making it less mobile. The easiest solution is to adjust the specific gravity of the glaze to 1.44 and flocculate it to thixotropic, this assures that the application is not too thick. Another measure is to add a little CMC gum (by replacing some of the water with gum solution). Lastly, use a blend of tin oxide and Zircopax, as in the G3926C version of the recipe, to opacify it.

This serious glaze crawling problem was solved with a simple addition

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

This is G2934Y white (with 10% Zircopax). I initially blamed the zircon for the crawling. But, since the slurry had settled somewhat I was able to remove about 15% of the water and replace it with CMC gum solution. The gum addition was not enough to slow down the drying much but it really improved reduced the problem! This likely means that adherence of the dried layer to the smooth bisque was the issue. This being said, there were still a couple of small spots where it crawled. The ultimate solution thus appears to be discovering the percentage of CMC gum and water needed to get the least loss of drying speed and while achieving integrity of glaze coverage. It is best to add the CMC gum as a powder at mixing time and blender mix the slurry thoroughly to be sure that it fully dissolves (watch for a rheology change on aging, that will demonstrate if mixing was thorough enough).

Alberta Slip crawling because it shrinks too much on drying

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Example of Alberta Slip which has been sprayed on dry ware and single fired. This happened because the slip shrunk during drying creating a network of cracks. These cracks become the crawl-points during firing.

Badly crawled glaze fired at cone 5 reduction

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

It was spray applied on the dried bowl (no bisque fire) an was too thick (not to mention under fired). But the main problem was a glaze recipe having too high a clay content. If a glaze has more than about 25% clay, consider a mix of the raw clay and calcined. For example, you can buy calcined kaolin to mix with raw kaolin. Or you can calcine the clay in bowls in your kiln by firing it to about 1200F.

Fixing a crawling problem with Ravenscrag Tenmoku

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Crawling of a cone 10R Ravenscrag Slip iron crystal glaze. The added iron oxide flocculates the slurry raising the water content, increasing the drying shrinkage. To solve this problem you can calcine part of the Ravenscrag Slip, that reduces the shrinkage.

Crawling glaze on slip cast ware is common

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

This cone 6 white glaze is crawling on the inside and outside of a thin-walled cast piece. This happened because the thick glaze application took a long time to dry, this extended period, coupled with the ability of the thicker glaze layer to assert its shrinkage, compromised the fragile bond between dried glaze and fairly smooth body. There are several measures that can be taken to solve this problem. The ware could be heated before glazing, the glaze applied thinner, or glazing the inside and outside could be done as separate operations (with a drying period between).

Same body, same glaze, same firing. Why did one crawl?

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

The body: M370. Glaze: G2934Y (with added green stain). Firing: Cone 6 drop-and-hold. Glazing method: dipping (using tongs). Thickness: The same. Surface: Clean on both. The difference: Clay wall thickness. The one on the right was cast much thinner so the glaze took a lot longer to dry. Common pottery glazes contain clays which need to shrink somewhat during drying. The bond with the bisque, although fragile, is normally enough to prevent cracking during drying. But drying needs to occur quickly with glazes containing no gum hardener - that is only possible when the body has enough porosity to absorb all the water quickly. Otherwise, cracks appear - and they become crawls during firing. A complicating factor is that stain and/or zircon additions make an already crawl-susceptible glaze even worse. One or a combination of the following can be done to minimize crawling on even very thin-walled pieces:

-Apply a thinner glaze layer.

-Heat the bisque before dipping.

-Glaze the inside and outside separately (with drying between).

-Deflocculate the glaze to reduce water content.

-Brush or spray on a CMC gummed version in multiple coats.

Crawling sanitary ware glaze sourcing Al2O3 from only feldspar

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

The original recipe had a very low clay content, sourcing almost all of its Al2O3 from feldspar instead. Although the glaze slurry was maintained at 1.78 specific gravity (an incredibly high value) and thus would have had very low shrinkage, it did not stick and harden well enough to the ware. Why? Lack of clay content in the glaze. The fix was to source much more of the Al2O3 from kaolin instead of feldspar. The reduction in feldspar shorted the glaze on KNaO and SiO2 so these were sourced from a frit and pure silica instead (the calculations to do this were done in Insight-live.com). The change also provided opportunity to substitute some of the KNaO with lower expansion CaO. This reduced the thermal expansion and reduced crazing issues.

Zircon glazes cover well but they have a problem

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

This sanitary ware tank lid was made in China. Notice how thick the white glaze is being applied to cover the iron containing body below. This is a testament to how opaque a zircon opacified glaze can be. Zircon often causes crawling (likely due to a combination of the effects of its fine particle size on drying properties and its tendency to stiffen the melt). Extra measures and constant attention to detail (e.g. glaze thickness, slurry rheology, avoidance of sharp contours on ware) are needed with such glazes.

Crawling glaze on the convex edges of sanitaryware

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Sanitaryware glazes are high in zircon, thus a stiff glaze melt is a part of their very nature. That means glaze crawling is a part of their nature! And, preventing it is a major effort by producers. Crawling most commonly happens inside acute contour changes (that thicken the layer), but crawl points can even occur on relatively flat surfaces. However, this time it appears on the outside of an abrupt curve. Factors that can cause crawling can compound on corners. During drying, soluble salts and binders in the clay tend to concentrate at edges and corners - these can affect glaze laydown (especially its thickness and adhesion). The slip casting process favours the concentration of the finest clay particles at the mold face, but corners see the most surface disruption during cleaning and tooling at the leather hard stage (which can expose coarser particles below the surface). Glazes containing clay must shrink somewhat during drying, a corner like this will be the first place a crack appears (and thus a crawl), especially if adhesion is not as good.

Mag carb causes crawling in higher amounts

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Example of two crawling glazes. Both have magnesium carbonate added to make this happen (around 10%). On the left at cone 04 on a terra cotta body, on the right at cone 6 on a porcelain. Magnesium carbonate also mattes glazes.

Why does the glaze on the right crawl?

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

This is G2415J Alberta Slip glaze on porcelain at cone 6. Why did the one on the right crawl? Left: thinnest application. Middle: thicker. Right thicker yet and crawling. All of these use a 50:50 calcine:raw mix of Alberta Slip in the recipe. While that appears fine for the two on the left, more calcine is needed to reduce shrinkage for the glaze on the right (perhaps 60:40 calcine:raw). This is a good demonstration of the need to adjust raw clay content for any glaze that tends to crack on drying. The Alberta Slip and Ravenscrag Slip page have information about how to calcine and calculate how much to use to tune the recipe to be perfect.

Here is what happens when a glaze has too much raw clay

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

This is an example of how a glaze that contains too much plastic clay has been applied too thick. It shrinks and cracks during drying and is guaranteed to crawl. This is raw Alberta Slip. To solve this problem you need to tune a mix of raw and roasted clay. Enough raw clay is needed to suspend the slurry and dry it to a hard surface, but enough calcine is needed to keep the shrinkage low enough that this cracking does not happen. Perhaps you have been using a glaze having a high percentage of clay and this does not happen - the reason is likely that the clay is not highly plastic.

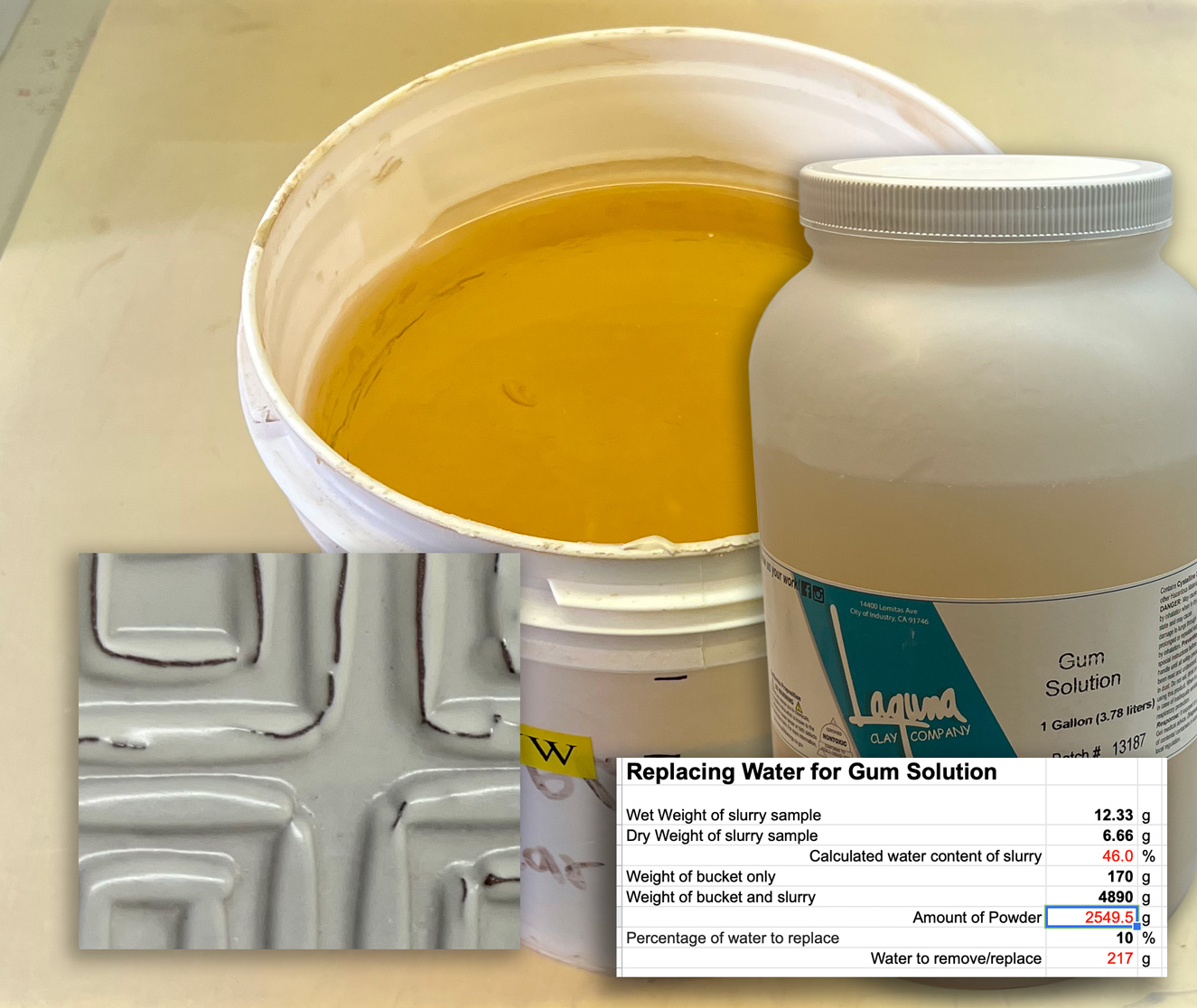

Fixing a crawling problem with a measured CMC addition

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

The problem: This dipping glaze is crawling (as shown on the glazed tile). Let's assume I have already checked to make sure the specific gravity is right and the slurry is thixotropic. Because it has settled a little there is an opportunity for plan B: Remove some of the water and replace it with gum solution. Shown here is a precise calculation of the exact water content of the slurry to replace 10% of the water with gum solution. But it is better to take a more conservative and easier approach: Replace one-twentieth of the water with gum solution (too much gum and the glaze will drip excessively and dry too slowly). Rather than be overly precise let's just guess: I have 5000g of slurry that is about 50% water, so that is 2500g of powder, so I need to remove 125g of water and replace it with 125g of Laguna gum solution. A good way is to use a sponge: Wet and wring it out first and then repeat touching it to the water surface and wringing it out into a container to get 125g. A propeller mixer is needed to mix in the added gum solution (it won't just stir in).

Here is why Albany Slip was hard to use: Crawling

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

This glaze is 85% Albany Slip and 20% Ferro Frit 3195. These bisque tiles were dipped in a brushing glaze version of it (just water and powder). The glaze is applied quite thin on the front tile and thicker on the back one. The material gelled slurries and required a lot of water to make them thin enough to use. For assured success, this or any glaze that had a high percentage required mixing the raw Albany Slip with a calcined Albany Slip (which people had to make on their own).

Multilayer crawling

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Oil-spot effects depend on being able to layer glazes. Normally, a black underneath and matte white over top. Using dipping glazes is obviously advantageous for this type of piece; the second dip covers the other half and creates the double layer needed. But dipping glazes contain clay in the recipe (almost always kaolin or ball clay), it satisfies multiple needs: It suspends the slurry, hardens the drying glaze, and supplies critical Al2O3 to the chemistry. The upper glaze here is a matte; so it needs extra Al2O3, which means it likely has extra clay. 20% kaolin (non-plastic like EPK, Grolleg, NZ) is about the maximum or the glaze will shrink too much when drying. If extra Gerstley Borate is added, then it will be worse. Drying cracks are the result when the fragile body-bond of the lower one fails to withstand the stresses of being rewetted and tugged upon by the upper layer being applied and drying. When the cracked double-layer begins to melt, it pulls itself into islands, leaving bare body between. That is called "crawling".

How to prevent this. Be smart about glaze layering and use recipe logic. The lower black can likely be adjusted to be a first coat dipping glaze. The clay content in the upper white one can be adjusted to reduce drying shrinkage (by splitting it between raw and roasted/calcined powder, or by using a clay having lower plasticity).

Do not glaze bisque ware when it is too wet

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

These mugs are quite thin walled. A glaze has just been applied to the inside. Notice how it has water logged the bisque (you can see the contrast at the base, where the clay is a little thicker and has not changed color yet). Although there may be enough absorbency that a glaze could be applied now, it would still not be a good idea because it would completely waterlog the piece and result in a very long drying time. This is bad, not only because of process logistics, but also because slow drying glazes almost always crack and lift from the bisque (causing crawling).

Glaze cracking during drying? Wash it off and then do this.

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

If your pottery glaze is doing on drying then it will crawl during firing. Wash it off, dry the ware. Then check the water content. If the glaze has worked fine in the past then it is likely going on too thick because the specific gravity is too high - just repeat cycles of adding a little water and dip testing (make it thixotropic if needed). But that was not the issue here. Glazes need clay to suspend and harden them, but too much clay means trouble. This was Ravenscrag Slip, a clay, being used pure as a cone 10R glaze. The glaze appeared to go in perfectly and it dried to the touch in ~20 seconds. But shrinkage continues after that, revealing after a couple of minutes. Fixing the issue was a matter of adding some roasted Ravencrag Slip to the bucket. That reduced the shrinkage and therefore the cracking. Any glaze containing excessive kaolin can be fixed the same way (trade some of the raw kaolin for calcined kaolin). Some glazes that contain plenty of clay also have bentonite - a simple fix for these is to simply remove the bentonite.

CMC Gum is magic for multi-layering, even for raw Alberta Slip

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

The glaze on the left is 85% of a calcine:raw Alberta Slip mix (40:60). It was on too thick so it cracked on drying (even if not too thick, if others are layered over it everything will flake off). The center piece has the same recipe but uses 85% pure raw Alberta Slip, yet it sports no cracks. It should be cracked much worse than #1. How is this possible? 1% added CMC Gum (via a gum solution) was added! This is magic, but there is more. It is double-layered! Plus very thick strokes of a commercial brushing glaze have been applied over that. Yet no cracks. CMC is the secret of dipping-glazes for multi-layering. The downside: More patience during dipping, they drip a lot and take much longer to dry.

Links

| Articles |

Understanding Glaze Slurry Properties

It is possible to have a glaze slurry that is a joy to use, but only if you understand the physics of the materials in the glaze recipe. |

| Articles |

Creating a Non-Glaze Ceramic Slip or Engobe

It can be difficult to find an engobe that is drying and firing compatible with your body. It is better to understand, formulate and tune your own slip to your own body, glaze and process. |

| Glossary |

Surface Tension

In ceramics, surface tension is discussed in two contexts: The glaze melt and the glaze suspension. In both, the quality of the glaze surface is impacted. |

| Glossary |

Glaze Crawling

A ceramic glaze fault that occurs during firing of the ware, the molten glaze pulls itself into islands leaving bare patches of body between. |

| Glossary |

Suspension

In ceramics, glazes are slurries. They consist of water and undissolved powders kept in suspension by clay particles. You have much more control over the properties than you might think. |

| Glossary |

Calcination

Calcining is simply firing a ceramic material to create a powder of new physical properties. Often it is done to kill the plasticity or burn away the hydrates, carbonates, sulfates of a clay or refractory material. |

| Glossary |

Ceramic Glaze Defects

Ceramic glaze defects include things like pinholes, blisters, crazing, shivering, leaching, crawling, cutlery marking, clouding and color problems. |

| Glossary |

Glaze Layering

In hobby ceramics and pottery it is common to layer glazes for visual effects. Using brush-on glazes it is easy. But how to do it with dipping glazes? Or apply brush-ons on to dipped base coats? |

| Troubles |

Glaze Pinholes, Pitting

Analyze the causes of ceramic glaze pinholing and pitting so your fix is dealing with the real issues, not a symptom. |

| Materials |

Alberta Slip

Albany Slip successor - a plastic clay that melts to dark brown glossy at cone 10R, with a frit addition it can also host a wide range of glazes at cone 6. |

| Materials |

Ravenscrag Slip

A light-colored silty clay that melts to a clear glaze at cone 10R, with a frit addition it creates a good base for a wide range of cone 6 glazes. |

| Materials |

Alberta Slip 1900F Calcined

|

| Materials |

Calcined Kaolin

This is kaolin powder that has been fired in a furnace to remove the 12% crystal water and render it non-plastic. |

| Materials |

Light Magnesium Carbonate

A refractory feather-light white powder used as a source of MgO and matting agent in ceramic glazes |

| Materials |

Alberta Slip 1000F Roasted

|

| Oxides | Sm2O3 - |

| By Tony Hansen Follow me on        |  |

Got a Question?

Buy me a coffee and we can talk

https://digitalfire.com, All Rights Reserved

Privacy Policy