| Monthly Tech-Tip | Feb 14-15, 2026 - Major Server Upgrade Done | No tracking! No ads! |

CoO (Cobalt Oxide)

Data

| Frit Softening Point | 1810C (From The Oxide Handbook) |

|---|

Notes

-Cobalt is the most powerful and stable colorant used in glass, glaze, enamel, and even paint. As little as 2 PPM can produce a recognizable tint, thus cobalt is often cut in a medium to make it easier to weigh and distribute in a mix.

-Various raw forms are available and all break down to cobaltous oxide (CoO), which is the stable form that combines with the glass melt to produce color. These include black stable cobalto-cobaltic oxide (cobaltosic oxide) Co3O4, which has a 93% conversion ratio and decomposes to liberate oxygen at 800C. Grey cobaltic oxide (Co2O3) is 90% CoO and mauve cobalt carbonate (CoCO3) has 63% effective stain content. Cobalt dioxide (CoO2) is not marketed for ceramics.

-Although cobalt has a high melting point by itself, is dissolves readily in most glazes and acts as a powerful flux, especially alkaline and boron types. This active nature causes it to diffuse, making it difficult to maintain a clean edge on painted decoration, especially overglaze. Decorated areas employing color in or on glaze can thus be locally more melted depending on the concentration of CoO or its particle size, this can result in increased tendency to blister or crawl in some glazes.

-It is very color dependable under both oxidizing and reducing furnace conditions, fast and slow firing. Cobalt is used in a wide array of decal inks, underglaze colors, glaze and body stains, and colored glazes. It is not volatile even at 1400C.

-Cobalt is a trace element in vegetables and an important vitamin (B12) in stock raising. Cobalt metal is used in steel and chrome alloys.

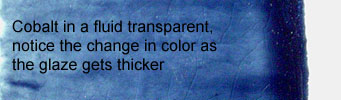

Cobalt in a transparent glaze: Color varies with thickness

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

If you add an opacifier to this the color will become pastel and lighter and vary less with thickness.

How do metal oxides compare in their degrees of melting?

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

These metal oxides have been mixed with 50% Ferro frit 3134 and fired to cone 6 oxidation. Chrome and rutile have not melted, copper and cobalt are extremely active melters, frothing and boiling. Cobalt and copper have crystallized during cooling. Manganese has formed an iridescent glass.

Ceramic Oxide Periodic Table

Pretty well all common traditional ceramic base glazes are made from less than a dozen elements (plus oxygen). Go to the full picture of this table and click or tap each of the oxides to learn more (on its page at digitalfire.com). When materials melt, they decompose, sourcing these elements in oxide form. The kiln builds the glaze from them, it does not care what material sources what oxide (assuming, of course, that all materials do melt or dissolve completely into the melt to release those oxides). Each of these oxides contributes specific properties to the glass. So, you can look at a formula and make a good prediction of the properties of the fired glaze. And know what specific oxide to increase or decrease to move a property in a given direction (e.g. melting behavior, hardness, durability, thermal expansion, color, gloss, crystallization). And know about how they interact (affecting each other). This is powerful. A lot of ceramic materials are available, hundreds - that is complicated when individual materials source multiple oxides. Viewing a glaze as a simple unity formula of ceramic oxides is just simpler.

Transform the yellow-white of cone 6 to blue-white of cone 10R

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Adding a little blue stain to a medium temperature transparent glaze can give it a more pleasant tone. Some iron is present in all stoneware bodies (and even porcelains), so transparent glazes never fire pure white. At cone 10 reduction they generally exhibit a bluish color (left), whereas at cone 6 they tend toward straw yellow (right). Notice the glaze on the inside of the center mug, it has a 0.1% Mason 6336 blue stain addition; this transforms the appearance to look like a cone 10 glaze (actually, you might consider using a little less, perhaps 0.05%). Blue stain is a better choice than cobalt oxide, the latter will produce fired speckle.

How reduction firing can affect glaze color

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

An example of how the same dolomite cobalt blue glaze fires much darker in oxidation than reduction. But the surface character is the same. A different base glaze having the same colorant might fire much more similar. The percentage of colorant can also be a factor in how similar they will appear. The identity of the colorant is important, some are less prone to differences in kiln atmosphere. Color interactions are also a factor. The rule? There is none, it depends on the chemistry of the host glaze, which color and how much there is.

Bleeding underglaze. Why?

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

This cobalt underglaze is bleeding into the transparent glaze that covers it. This is happening either because the underglaze is too highly fluxed, the over glaze has too high of a melt fluidity or the firing is being soaked too long. Engobes used under the glaze (underglazes) need to be formulated for the specific temperature and colorant they will host, cobalt is known for this problem so it needs to be hosted in a less vitreous engobe medium. When medium-colorant compounds melt too much they bleed, if too little they do not bond to the body well enough. Vigilance is needed to made sure the formulation is right.

Pure cobalt carbonate and copper carbonate at 1850F

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

Cobalt carbonate (top) and copper carbonate (bottom). Left is the raw powder plastic-formed into a sample (with 2% veegum). Right: fired to 1850F. The CuCO3 is quickly densifying over the past 100 degrees and should begin to melt soon. It is long past the fuming stage.

Links

| Materials |

Cobalt Carbonate

|

| Materials |

Cobalt Oxide

|

| Materials |

Stain (blue)

|

| Glossary |

Limit Formula

A way of establishing guideline for each oxide in the chemistry for different ceramic glaze types. Understanding the roles of each oxide and the limits of this approach are a key to effectively using these guidelines. |

Mechanisms

| Body Color | In magnesia glazes a color range is from violet to lilac is possible. |

|---|---|

| Glaze Color | Cobalt is a classic and reliable blue colorant at all temperatures and in most types of glazes. The shade of blue can, however, be affected in many ways by the presence of different oxides. Cobalt is powerful and often less than 1% will give strong color. If the color needs to be toned down, additions of iron, titanium, rutile and nickel may work. |

| Glaze Color | Cobalt is often calcined with alumina and lime for soft underglaze colors. Stains often employ mixes of alumina, cobalt, and zinc for softer blue colors. |

| Glaze Color | Cobalt is used in combination with manganese and selenium to mask excess yellow coloration (yellow plus blue gives green which is masked by the pink of selenium). |

| Glaze Color | Combinations with iron and manganese can give a slate blue. |

| Glaze Color | With barium shades of blue-green are possible. |

| Glaze Color | With chrome and manganese blue-black and black are common. |

| Glaze Color | With chrome and copper, cobalt can yield tints from pure cobalt blue, to greenish-blue, to the green of chromium. These effects work best when silica is not too high and there is adequate alumina. |

| Glaze Color | When cobalt occurs with manganese (i.e. 1-3% cobalt carb, 3-5% manganese carb), purples and violets can be made. Less cobalt will lighten the color. This effect works well in magnesia glazes. In high magnesia glazes, 1-2% cobalt alone will give purple. Add tin to move the color toward lavender. |

| Glaze Color | With adequate SiO2 and high MgO (0.4 molar), purple, violet, lavender, and pinks can be made using 1% or more CoO. Mimimizing boron, alumina, and KNaO will help prevent it from turning blue. Note that the high MgO will generally make the glaze matte and it could suffer some ill effects associated with excessive MgO. |

| Glaze Color | With MgO, SiO2, and B2O3, red, voilet, lavender, and pinks can be made. |

| By Tony Hansen Follow me on        |  |

Got a Question?

Buy me a coffee and we can talk

https://digitalfire.com, All Rights Reserved

Privacy Policy