| Monthly Tech-Tip | Feb 14-15, 2026 - Major Server Upgrade Done | No tracking! No ads! |

A cereal bowl jigger mold made using 3D printing

Beer Bottle Master Mold via 3D Printing

Better porosity for Brown Sugar Savers

Build a kiln monitoring device

Celebration Project

Coffee Mug Slip Casting Mold via 3D Printing

Comparing the Melt Fluidity of 16 Frits

Cookie Cutting clay with 3D printed cutters

Evaluating a clay's suitability for use in pottery

Make a mold for 4-gallon stackable calciners

Make Your Own Pyrometric Cones

Make your own sieve shaker to process ceramic slurries

Making a high quality ceramic tile

Making a Plaster Table

Making Bricks

Making our own kiln posts using a hand extruder

Medalta Ball Pitcher Slip Casting Mold via 3D Printing

Medalta Jug Master Mold Development

Mold Natches

Mother Nature's Porcelain - Plainsman 3B

Mug Handle Casting

Nursery plant pot mold via 3D printing

Pie-Crust Mug-Making Method

Plainsman 3D, Mother Nature's Porcelain/Stoneware

Project to Document a Shimpo Jiggering Attachment

Roll, Cut, Pull, Attach Handle-making Method

Slurry Mixing and Dewatering Your Own Clay Body

Testing a New Load of EP Kaolin

Using milk as a glaze

Better porosity for Brown Sugar Savers

Terra Cotta brown sugar savers are big business, being made by hundreds of companies and individuals. Their entire reason for existence is porosity, the ability to absorb lots of water and pack it into a small object that is not itself "wet". Of course, they are in direct contact with food, so one naturally expects that the water they contain is not leaching anything undesirable. However, terra cotta clays have an issue regarding the safety of being in contact with food: They are sedimentary materials, nature's trace element library of the periodic table. Their geological origins, by definition, make them contaminated clays (contaminated with iron, calcium, magnesium, sodium, and potassium in significant amounts).

Microscopically, cays are particles. But, unlike kaolin or ball clay, the particle mix in terracottas is not one homogeneous mineral; there is a wide range. And, many of the particles are not clay. And, many of them also have solubility. This is a problem in heavy clay manufacturing industries (e.g. brick and tile), it is referred to as "soluble salts". Industry adds barium carbonate to precipitate these salts as the clay dries (preventing their migration to the surface with the water).

The impurity particles also bring a decisive benefit: Better fired maturity, meaning less energy is needed for firing. In fact, the more the impurities, the lower the temperature they can be fired to. All of this has a bearing on using such clays to make brown sugar savers. The savers are fired to the lowest possible temperature to maximize the porosity (it drops as temperature increases). Standard terra cotta clays need to be fired to cone 06 at least to make them reasonably resistant to chipping or breaking at the edges. The typical porosity of a terracotta at cone 06 will be about 8-12% (as measured by the SHAB test). But, the lower the temperature, the less likely that soluble particles will have developed any glassy phase to create a ceramic that is resistant to leaching (meaning they retain any solubility).

For many years, I have suggested that people consider clays having much lower levels of soluble contaminants. While at the same time using ones that have higher porosity. Consider a surprising fact that most potters see but don't really notice: High-temperature clays have bisque-stage strength levels just as good as terracottas! This is because low temperatures in a kiln do not "fire" clay, they "sinter" it. There is no development of a glassy phase to cement particles together. Potters also notice that bisqued porcealin absorbs water much faster than terracottas. This means that a mix of ball clay or kaolin with a filler has the potential to work better for this purpose. What is the best filler we have seen? Dolomite (and also calcium carbonate, e.g. 60% ball clay and 40% dolomote). We see up to 30% porosity (compared to commercial savers whose porosity might be as low as 10%). These two materials are far more homogeneous than a terra cotta and have levels of soluble salts that can be almost undetectable. Another benefit is almost zero fired shrinkage. However, the material fires white, so iron oxide has to be added to stain it the terracotta color. There is an issue, however: Dolomite bodies don't react to iron oxide in the same way. You can mitigate this by surface coating at the leather hard or dry stage (or reducing the percentage of dolomite).

Related Information

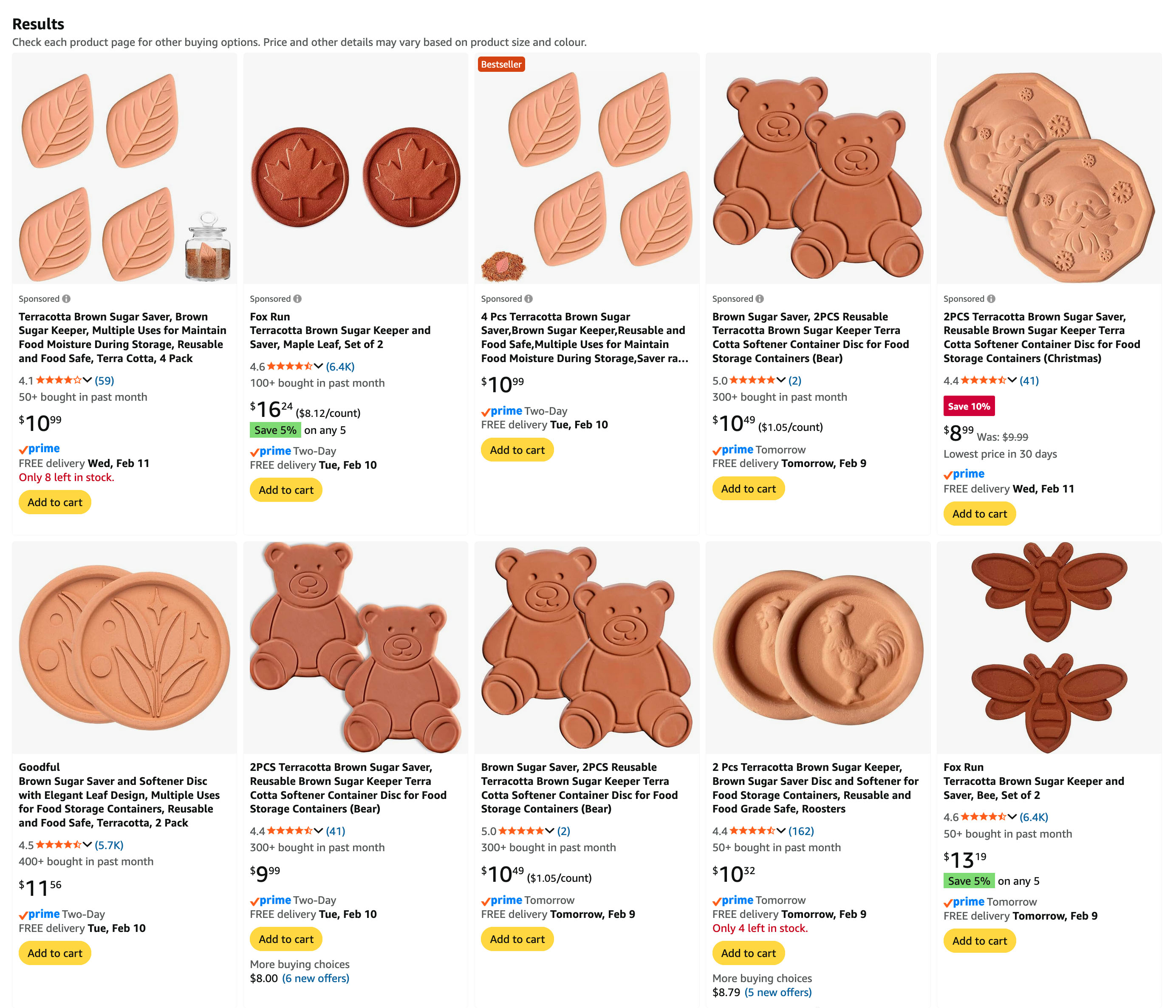

Terra Cotta brown sugar savers on Amazon - you can do better

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

These are sold at a wide range of prices. We bought two of these and tested their porosities. One absorbed 10% of its weight in water (that means a 30-gram saver soaks up only 3 grams of water). The other soaked up three times as much. But, the manufacturer of that one took advantage of the extra porosity by making a saver half the weight of the others. And, according to my firing tests, it is not terracotta (they are most likely iron-staining a mix of commercial kaolin or ball clay and adding a filler, using the word "terracotta" as a description of the color).

Are dolomite clay bodies OK?

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

The L4410P cone 04 body (Plainsman Snow), although high in Dolomite has proven to be very resilient, but not just in physical strength. This was developed as an alternative to talc bodies. This tile has not spalled despite cycling it three times through an hours-long water immersion then a week-long freezer stay. The mug has cracked after four years of storage on a shelf in our lab (but it has 60% dolomite vs. Snow's 40%). If the percentage of dolomite (or calcium carbonate) is too high, cracks like this can develop as the dolomite hydrates. For use in pottery, these can be avoided by treating pieces with a silicone sealant.

How to make a zero fired shrinkage clay

This picture has its own page with more detail, click here to see it.

This is Plainsman BGP, a terra cotta, mixed with 30% dolomite. Note the "DSHR" column in the SHAB test data (third last column): The drying shrinkage still averages over 7% even with the 30% dolomite, so BGP is very plastic. Notice the "FSHR" (fired shrinkage) column, it is negative for the first five test bars fired at cone 05-01, which means the bars grew in size! But notice the shrinkage hits 0% at cone 1 (bar #6). By cone 2 the trend has reversed to 0.3% shrinkage. The #6 bar is appears to be vitrifying, the color is darkening and it is strong. But notice the last "ABS" column (water absorption), it is 18.7%! This body was intended as a high-porosity ceramic at the lower ranges (it has 25% porosity at cone 05), but the dolomite is also slowing the densification as it goes through the vitrification process. Without the dolomite the top bar would be melting! By cone 1 its firing shrinkage would be 7%, and the porosity would be zero. Is this technique practical? Yup! The entire monoporosa wall tile industry is based on it!

| By Tony Hansen Follow me on        |  |

Got a Question?

Buy me a coffee and we can talk

Let’s work together to develop your porosity clay

Tap the chat icon on the lower right

https://digitalfire.com, All Rights Reserved

Privacy Policy